Ah, the 60s. Both the studio system and the production code collapsed as Hollywood struggled to remain relevant during a time of great social upheaval. The Academy alternated between nominating films that took chances and nominating films that cost a lot of money. It led to some odd best picture lineups and some notable snubs!

1960: Psycho Is Not Nominated For Best Picture and Anthony Perkins Is Not Nominated For Best Actor

To be honest, considering that the Academy has never really embraced horror as a genre and spent most of the 60s nominating big budget prestige pictures, it’s a bit surprising that Psycho was actually nominated for four Oscars. Along with being nominated for its production design and its cinematography, Psycho also won nominations for Alfred Hitchcock and Janet Leigh. However, Anthony Perkins was not nominated for Best Actor, despite giving one of the most memorable performances of all time. The film literally would not work without Perkins’s performance and, considering that Perkins pretty much spent the rest of his career in the shadow of Norman Bates, it’s a shame that he didn’t at least get a nomination for his trouble. Psycho was also not nominated for Best Picture, despite being better remembered and certainly more influential than most of the films that were.

1962: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance Is Almost Totally Snubbed

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was not totally snubbed by the Academy. It received a nomination for Best Costume Design. But still, it deserved so much more! John Ford, James Stewart, John Wayne, Lee Marvin, Vera Miles, and the picture itself were all worthy of nominations. Admittedly, 1962 was a year full of great American films and there was a lot of competition when it came to the Oscars. Still, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance definitely deserved a best picture nomination over the bloated remake of Mutiny on the Bounty. Today, if the first Mutiny on the Bounty remake is known for anything, it’s for Marlon Brando being difficult on the set. But The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is still remembered for telling us to always print the legend.

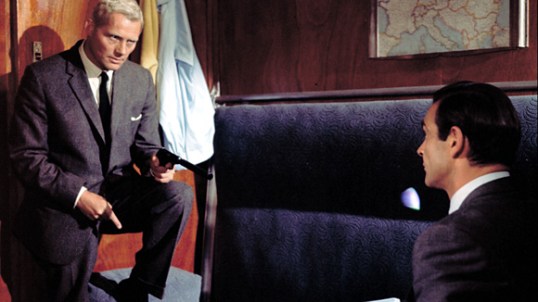

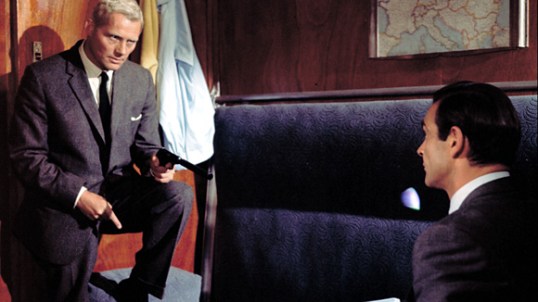

1964: From Russia With Love Is Totally Snubbed

The same year that the Academy honored George Cukor’s creaky adaptation of My Fair Lady, it totally ignored my favorite James Bond film. From Russia With Love is a Bond film that works wonderfully as both a love story and a thriller. Sean Connery, Lotte Lenya, Robert Shaw, and Terence Young all deserved some award consideration. From Russia With Love was released in the UK in 1963. In a perfect world, it would have also been released concurrently in the U.S., allowing From Russia With Love to be the film that gave the the Academy the chance to recognize the British invasion. Instead, Tom Jones was named the Best Picture of 1963 and From Russia With Love had to wait until 1964 to premiere in the U.S. It was snubbed in favor of one of old Hollywood’s last grasps at relevance.

1964: Slim Pickens Is Not Nominated For Best Supporting Actor

Playing three separate roles, Peter Sellers dominates Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb. But, as good as Sellers is, the film’s most memorable image is definitely Slim Pickens whooping it up as he rides the bomb down to Earth. George C. Scott and Sterling Hyaden also undoubtedly deserved some award consideration but, in the end, Pickens is the one who brings the film to life even as he helps to bring society to an end.

1967: In Cold Blood Is Not Nominated For Best Picture

In Cold Blood, though not a perfect film, certainly deserved a nomination over Dr. Doolittle. In Cold Blood is a film that still has the power to disturb and haunt viewers today. Dr. Doolittle was a box office debacle that was nominated in an attempt to help 20th Century Fox make back some of their money.

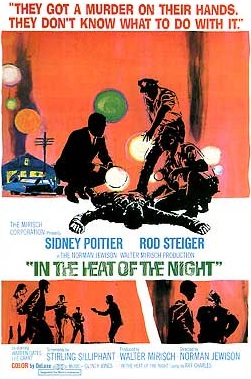

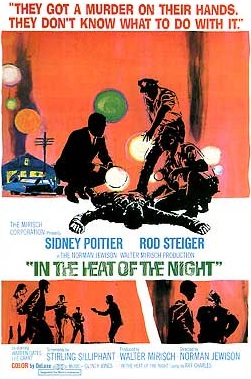

1967: Sidney Poitier Is Not Nominated For Best Actor For In The Heat Of The Night

In 1967, Sidney Poitier starred in two of the films that were nominated for Best Picture but somehow, he did not pick up a nomination himself. His restrained but fiercely intelligent performance in In The Heat Of The Night provided a powerful contrast to Rod Steiger’s more blustery turn. That Poitier was not nominated for his performance as Virgil Tibbs truly is one of the stranger snubs in Academy history. (If I had to guess, I’d say that the Actors Branch was split on whether to honor him for In The Heat of the Night or Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner or even for To Sir With Love and, as a result, he ended up getting nominated for none of them.)

1968: 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes Are Not Nominated For Best Picture

Neither one of these classic science fiction films were nominated for Best Picture, despite the fact that both of them are far superior and far more influential than Oliver!, the film that won that year.

1968: The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly Is Totally Ignored

Not even Ennio Morricone’s score received a nomination!

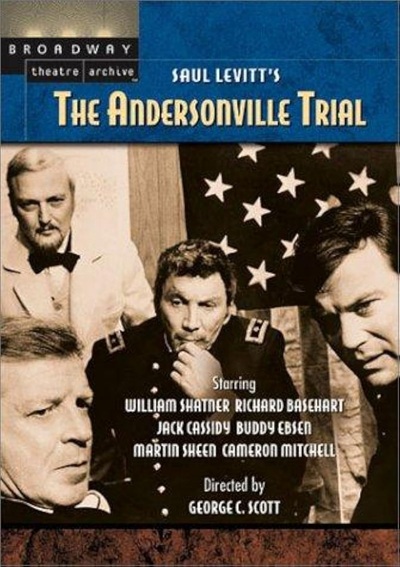

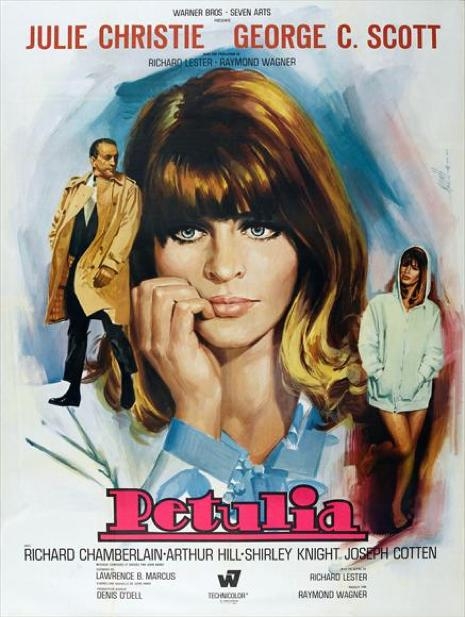

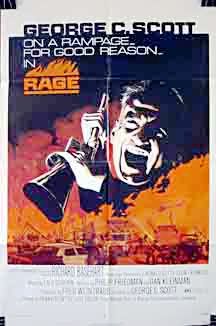

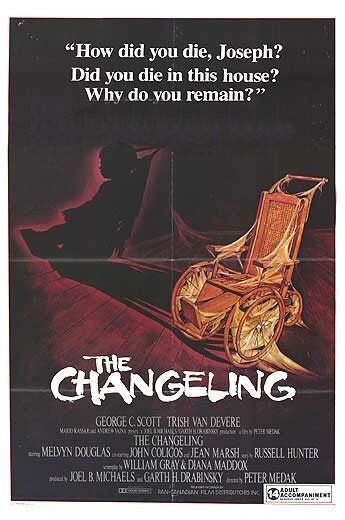

1968: Petulia Is Totally Snubbed

Seriously, I don’t know what was going on with the Academy in 1968 but it seems they went out of their way to ignore the best films of the year. Richard Lester’s Petulia is usually cited as one of the definitive films of the 60s but it received not a single Oscar nomination. Not only did the film fail to receive a nomination for Best Picture but Richard Lester, George C. Scott, Julie Christie, Shirley Knight, Richard Chamberlain, and the film’s screenwriters were snubbed as well.

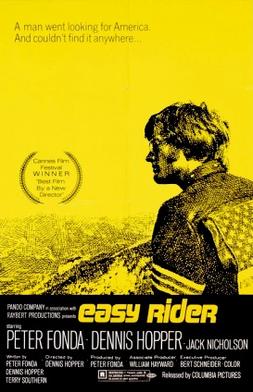

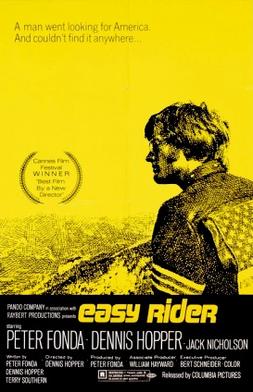

1969: Easy Rider Is Not Nominated For Best Picture

Yes, I know. Easy Rider is a flawed film and there are certain moments that are just incredibly pretentious. That said, Easy Rider defined an era and it also presented a portrait of everything that was and is good, bad, and timeless about America. The film may have been produced, directed, and acted in a drug-razed haze but it’s also an important historical document and it was also a film whose success permanently changed Hollywood. Certainly, Easy Rider’s legacy is superior to that of Hello, Dolly!

Agree? Disagree? Do you have an Oscar snub that you think is even worse than the 10 listed here? Let us know in the comments!

Up next: It’s the 70s!