The 1983 film, 10 to Midnight, opens with LAPD detective Leo Kessler (played by legendary tough guy Charles Bronson) sitting at his desk in a police station. He’s typing up a report and taking his time about it. A reporter who is in search of a story starts to bother Leo.

“Jerry,” Leo tells him, “I’m not a nice person. I’m a mean, selfish son-of-a-bitch. I know you want a story but I want a killer and what I want comes first.”

It’s a classic opening, even if Leo isn’t being totally honest. Yes, he can be a little bit selfish but he’s really not as mean as he pretends to be. He may not know how to talk to his daughter Laurie (Lisa Eilbacher) but he is also very protective of her and he wants to be a better father than he’s been in the past. He may roll his eyes when he discovers that Detective Paul McAnn (Andrew Stevens) is the son of a sociology professor but he still tries to act as a mentor to his younger partner. Leo may complain that the criminal justice system “protects those maggots like they’re an endangered species” but that’s just because he’s seen some truly disturbing things during his time on the force and, let’s face it, Leo has a point. When one of Laurie’s friends is murdered, Leo is convinced that Warren Stacy (Gene Davis) is the murderer and he’s determined to do whatever he has to do to get Warren off the streets. “All those girls,” Leo snarls when he sees Warren, his tone letting us know that his mission to stop Warren is about more than just doing his job.

Warren Stacy is handsome, athletic, and he has good taste in movies. (He’s especially a fan of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Just don’t try to trick him by saying Steve McQueen played the Sundance Kid.) Warren is also a total creep, the type of guy who complains that a murder victim “wasn’t a good person,” because she trashed him in her diary. When Leo takes a look around Warren’s apartment, he finds not only porn but also a penis pump. (“It’s for jacking off!” Leo yells at Warren, enunciating the line as only Charles Bronson could.) Warren is also a murderer but he’s a clever murderer, the type who sets himself up with an alibi by acting obnoxiously in a movie theater. Warren strips nude before killing his victims, in order to make sure that he doesn’t leave behind any evidence. (This film was made in the days before DNA testing.)

Leo knows that Warren is guilty but, as both his gruff-but-fair captain (Wilford Brimley, naturally) and the D.A. (Robert F. Lyons) point out, he has no way to prove it. When Warren starts to stalk Laurie and her friends (including Kelly Preston), Leo decides that he has no choice but to frame Warren. But when Warren’s amoral attorney, Dave Dante (Geoffrey Lewis, giving a wonderfully sleazy performance), threatens to call McAnn to the stand, McAnn has to decide whether to tell the truth or to join Leo in framing a guilty man.

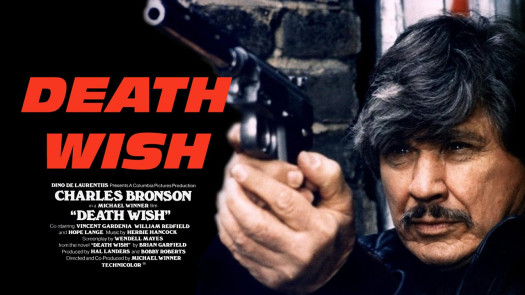

10 to Midnight is a violent, vulgar, and undoubtedly exploitive film, one that features a ham-fisted message about how the justice system is more concerned with protecting the rights of the accused as opposed to lives of the innocent. And yet, in its gloriously pulpy way, this is also one of Bronson’s best films. It’s certainly my personal favorite of the films that he made for Cannon.

Director J. Lee Thompson and Charles Bronson were frequent collaborators and Thompson obviously knew how to get the best out of the notoriously reserved actor. Bronson was not known for his tremendous range but he still gives one of his strongest performances in 10 to Midnight, playing Leo as being not just a determined cop but also as an aging man who is confused by the way the world is changing around him. Stopping Warren isn’t just about justice. It’s also about fighting back against the the type of world that would create a Warren Stacy and then allow him to remain on the streets in the first place. Interestingly, though Leo doesn’t hesitate when it comes to framing Warren, he is also sympathetic to McAnn’s objections. Unlike other Bronson characters, Leo doesn’t hold a grudge when his partner questions his methods. Instead, he simply know that McAnn hasn’t spent enough time in the real world to understand what’s at stake. McAnn hasn’t given into cynicism. He hasn’t decided that the best way to deal with his job is to be a “mean son of a bitch.” Bronson and Andrew Stevens, who had worked together in the past, have a believable dynamic. McAnn looks up to Leo but is also conflicted by his actions. Leo may be annoyed by McAnn’s reluctance but he also respects him for trying to be an honest cop. Their partnership feels real in a way that sets 10 to Midnight apart from so many other films about an older cop having to deal with an idealistic partner.

One of the most interesting things about the film is Leo’s relationship with his daughter, Laurie. Over the course of the film, Leo and Laurie go from barely speaking to bonding over liquor and their shared regrets about the state of the justice system. When McAnn first meets Laurie, she’s offended when McAnn suggests that she takes after her father. But, as the film progresses, she comes to realize that she and Leo have much in common. (To be honest, I related quite a bit to Laurie, especially as I’ve recently come to better appreciate how much of my own independent nature was inherited from my father.) Lisa Eilbacher and Charles Bronson are believable as father-and-daughter and they play off of each other well. The scenes between Laurie and Leo give 10 to Midnight a bit more depth than one might otherwise expect from a Bronson Cannon film. Leo isn’t just trying to protect his daughter and her roommates from a serial killer. He’s also trying to be the father who he wishes he had been when she was younger. He’s trying to make up for lost time, even as he also tries to keep Warren Stacy away from his family.

As played by Gene Davis, Warren Stacy is one of the most loathsome cinematic villains of all time. Warren’s crimes are disturbing enough. (Indeed, the surreal sight of a naked and blood-covered Warren Stacy stalking through a dark apartment is pure nightmare fuel.) What makes Warren particularly frightening is that we’ve all had to deal with a Warren Stacy at some point in our life. He’s the sarcastic and easily offended incel who thought he was entitled to a phone number or a date or perhaps even more. As I rewatched this movie last night, I wondered how many Warrens I had met in my life. How many potential serial killers have any of us unknowingly had to deal with? Warren tries to strut through life, smirking and going out of his way to let everyone know that he knows more than they do but the minute that Leo turns the table on him, Warren starts whining about he’s being treated unfairly. During his final, disturbing rampage, Warren yells that his victims aren’t being honest with him, blaming them for his actions. The film deserves a lot of credit for not turning Warren into some sort of diabolical and erudite supervillain. He’s not Hannibal Lecter. Instead, like all real-life serial killers, he’s a loser who is looking for power over those to whom he feels inferior and for revenge on a world that he feels owes him something. He’s a realistic monster and that makes him all the more frightening and the film all the more powerful. Warren is the type of killer who, even as I sit here typing this, could be walking down anyone’s street. He’s such a complete monster that it’s undeniably cathartic whenever Leo goes after him.

How delusional is Warren Stacy? He’s delusional enough to actually taunt Charles Bronson! At one point, Warren informs Leo that he can’t be punished for being sick. Warren announces that, when he’s arrested, he might go away for a while but he’ll be back and there’s nothing Leo can do about it. (The suggestion, of course, is that Warren will be back because he committed his crimes in California and all the judges were appointed by a bunch of bleeding heart governors. Warren may not say that out loud but we all know that is the film’s subtext. Some people may agree with the film, some people may disagree. Myself, I’m against the death penalty because I think it’s a prime example of government overreach but I still cheered the first time that I heard Clint Eastwood say, “Well, I’m all torn up about his rights,” in Dirty Harry.) How does Leo react to Warren’s taunts? I can’t spoil the film’s best moment but I can tell you that 10 to Midnight features one of Bronson’s greatest (and, after what we’ve just seen Warren do, most emotionally satisfying) one-lines.

The title has nothing to do with anything that happens in the film. In typical Cannon fashion, the film’s producers came up with a snappy title (and 10 to Midnight is a good one) and then slapped it onto a script that was previously called Bloody Sunday. Fortunately, as long as Bronson is doing what he does best, it doesn’t matter if the title makes sense. And make no mistake. 10 to Midnight is Bronson at his best.

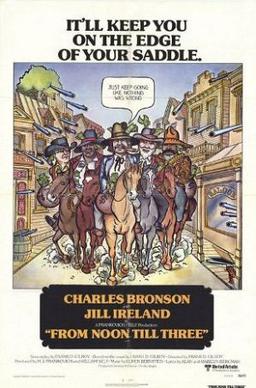

Dr. Laurence Jeffries (Anthony Perkins) is an American-born neurosurgeon living in the UK. One night, as Dr. Jeffries is preparing to head home, he meets a confused and frightened man who is identified in the credits as being The Stranger and who is played by Charles Bronson. The Stranger has no memory of who he is or how he came to be where he is. Dr. Jeffries takes the Stranger back to his house. Dr. Jeffries says that he often takes patients back home for overnight observation but it turns out that he has more than treatment on his mind. Dr. Jeffries knows that his wife, Frances (Jill Ireland, who was Bronson’s offscreen wife), has been cheating on him with her French lover. What if Dr. Jeffries can convince the Stranger that Frances is married to and cheating on him? Could The Stranger, who may have already attacked another woman on the beach, be manipulated into murdering Frances’s lover?

Dr. Laurence Jeffries (Anthony Perkins) is an American-born neurosurgeon living in the UK. One night, as Dr. Jeffries is preparing to head home, he meets a confused and frightened man who is identified in the credits as being The Stranger and who is played by Charles Bronson. The Stranger has no memory of who he is or how he came to be where he is. Dr. Jeffries takes the Stranger back to his house. Dr. Jeffries says that he often takes patients back home for overnight observation but it turns out that he has more than treatment on his mind. Dr. Jeffries knows that his wife, Frances (Jill Ireland, who was Bronson’s offscreen wife), has been cheating on him with her French lover. What if Dr. Jeffries can convince the Stranger that Frances is married to and cheating on him? Could The Stranger, who may have already attacked another woman on the beach, be manipulated into murdering Frances’s lover?