“You want to shoot me, go ahead. It won’t matter. I’ve seen things you wouldn’t believe.” — The Stranger

The Western Wound: Horror, History, and the Haunting of Frontier Mythology

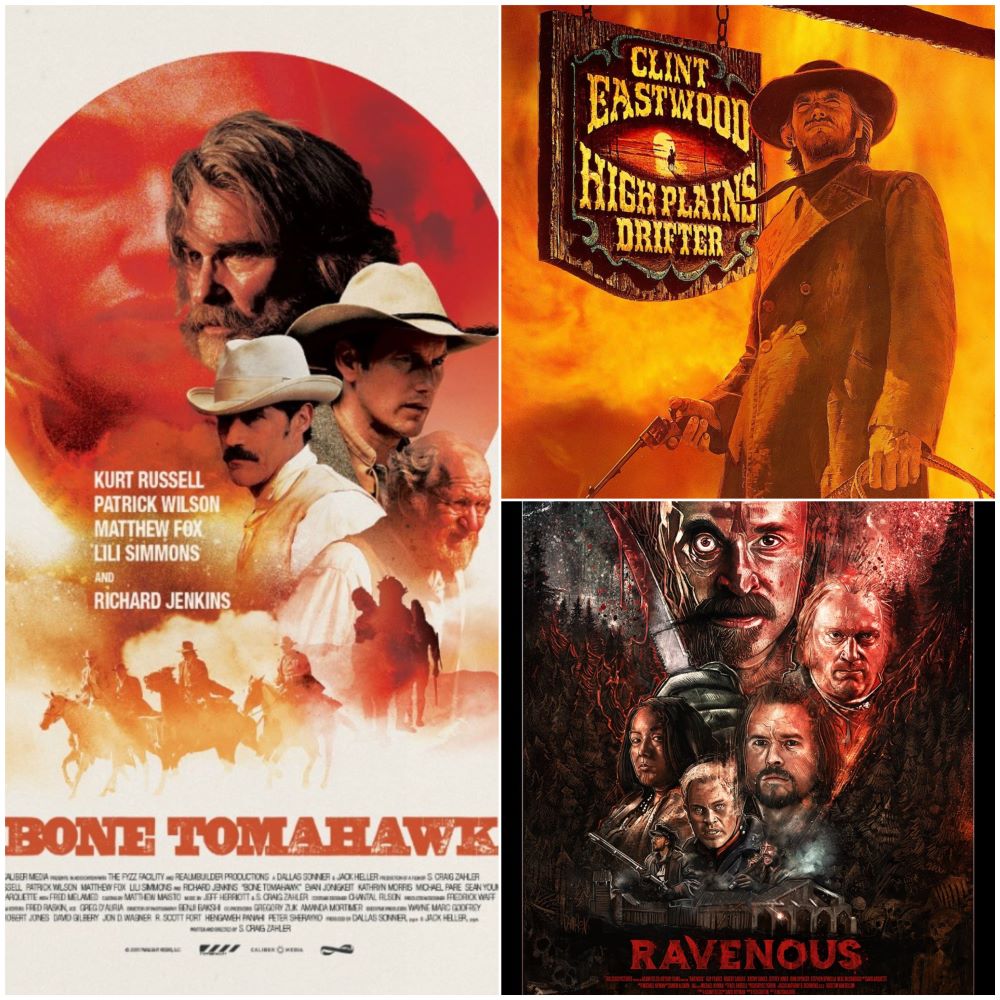

Horror profoundly shapes, distorts, and reframes the American Western, complicating familiar narratives of lawmen and outlaws with the uncanny specter of trauma, dread, and evil. Few films demonstrate this transformation more powerfully than Ravenous (1999), Bone Tomahawk (2015), and High Plains Drifter (1973). These three Westerns push beyond genre conventions, leveraging horror’s capacity to unsettle, destabilize, and haunt—creating experiences that are as philosophically provocative as they are viscerally unsettling. Rather than merely incorporating horror aesthetics into a Western setting, each film employs horror as a core thematic device to interrogate violence, community, morality, and the dark legacies of frontier expansion.

The Haunted Frontier: Atmosphere and the Specter of Evil

High Plains Drifter’s isolation in the arid Nevada desert is more than a physical setting; it externalizes the moral barrenness and guilt festering within the town of Lago. The oscillation between relentless sunlight and dense fog creates a hallucinatory space where natural laws are suspended, and supernatural retribution manifests. Central water imagery—the fog rolling off the lake, the lake itself—serves as a liminal zone, symbolizing the boundary between life and death, past and present, justice and vengeance. The Stranger’s spectral emergence from the desert heat haze hints at his otherworldly nature, turning the town’s landscape into a haunted battleground where redemption is elusive and suffering endemic.

Ravenous’s setting in the snowy Sierra Nevada mountains during the Mexican-American War imbues its horror with claustrophobic dread. Fort Spencer’s remoteness in the face of towering, hostile peaks and unrelenting winter transforms the natural environment into a gothic prison. This wilderness is both physical and psychological, oppressive in its vastness and merciless in its cold. The film uses this setting to amplify the existential terror wrought by cannibalism, suggesting an inescapable cycle of consumption where survival becomes monstrous. Deep shadows, filtered natural lighting, and long quiet scenes evoke dread as much as extreme violence.

In Bone Tomahawk, the stark, sunbaked deserts and towering rock formations of the American Southwest form an ominous landscape embodying ancient and unknowable horror. The frontier town is a fragile outpost at civilization’s edge, surrounded by a wild, menacing wilderness. The deep canyons serve as metaphorical gateways to past atrocities, echoing the silent histories of indigenous trauma and colonial violence. The oppressive silence and vastness underscore humanity’s diminutiveness and vulnerability, while the jagged terrain symbolizes the harshness of both nature and history’s brutal forces.

Monstrous Transformation: The Horror Within

The Stranger in High Plains Drifter manifests the blurring boundaries between justice and vengeance, heroism and monstrosity. His actions—including an unsettling rape scene—force a confrontation with the darkest aspects of human nature, showing how violence corrupts even those who claim righteousness. His ghostly status and ruthless methodology suggest he is a representation of collective guilt made tangible, punishing the town’s sins with otherworldly finality. The film invites viewers to question whether vengeance restores balance or merely perpetuates horror.

In Ravenous, cannibalism literalizes the primal urge to consume not only flesh but identity and sanity, transforming survivors into monsters. The character Ives, charismatic and terrifying, embodies this transformation, seducing others into a vortical descent of brutality. The film’s psychological horror arises from the contagion of hunger and madness, the breakdown of social and moral order amid desolation. It probes existential questions about survival, morality, and the dissolution of self.

Bone Tomahawk depicts transformation through the confrontation with an ancient, savage tribe whose brutality transcends ordinary human evil. The characters’ exposure to this primordial terror strips away civilized facades, forcing characters and viewers to acknowledge the latent barbarity within humanity. The film’s horror is both external—in the violent acts of the tribe—and internal—in the psychological unravelling of the rescue party. This duality highlights the wilderness as both physical terrain and psychic landscape of primal fear.

The Community and the Failures of Civilization

The communal failure in High Plains Drifter reveals how collective cowardice and betrayal corrupt society. Lago’s townsfolk enable the marshal’s murder and face the Stranger’s supernatural justice as a consequence. Their moral bankruptcy transforms the town into a cursed locus of horror, symbolizing how collective sin corrupts the social fabric and invites ruin.

Ravenous portrays community breakdown within the remote outpost, where isolation breeds paranoia, selfishness, and violence. The collapse of trust and order mirrors the broader failure of frontier society to contain human baseness under extreme conditions, suggesting society itself is a fragile construct vulnerable to collapse.

In Bone Tomahawk, the fragile rescue party embodies the precariousness of social cohesion facing profound evil. Their doomed mission stresses how thin the veneer of civilization is, shattering under pressure from ancient horrors. The film critiques assumptions of order and control, emphasizing the ease with which human society can crumble.

Violence, Justice, and the Ethical Horror

Violence in High Plains Drifter is unending, spectral, and morally ambiguous. The Stranger’s vengeance refuses neat closure, illustrating cycles of violence that leave deeper scars rather than justice. The film redefines violent retribution as torment, destabilizing conventional heroic narratives.

Ravenous entwines violence with survival horror and existential dread. The ritualistic cannibalism is a metaphor for moral and spiritual corrosion, forcing characters and audiences to face the horrors wrought by the primal fight for survival at civilization’s edge.

Bone Tomahawk presents violence as slow, ritualistic, and ancient—an elemental force indifferent to human ethics. Its stark, realistic depiction immerses viewers in fear and helplessness, rejecting conventional catharsis and highlighting the terror of primal brutality.

Subtext and Symbolism: Horror as the Depths of Humanity

High Plains Drifter blends ghostly and surreal imagery to explore unresolved sin and cultural guilt. The Stranger is both avenger and specter of collective trauma, with symbolic elements—such as the red-painted town and unmarked graves—that deepen the meditation on punishment and desolation.

Ravenous uses cannibalism and wilderness as symbols of consumption and destruction intrinsic to frontier expansion. Horror here reflects existential struggles with survival, cultural annihilation, and moral ambiguity, set against an environment of engulfing nature and history.

Bone Tomahawk evokes frontier horror as a metaphor for repressed histories and cultural erasure. The savage tribe symbolizes ancestral trauma, while the desolate landscapes underscore the lingering presence of buried horrors that haunt the Western imagination.

The Western Genre as a Wound Haunted by Horror

Ravenous, Bone Tomahawk, and High Plains Drifter deepen the Western genre’s reckoning with violence, morality, and civilization’s fragility. Ravenous allegorizes hunger and expansion’s destructive appetite through cannibalism, revealing survival’s costs to identity and culture. Bone Tomahawk exposes historical violence and trauma encoded in landscape and myth, demonstrating Western justice’s limits. High Plains Drifter dramatizes unresolved guilt and vengeance through spectral retribution, challenging sanitized Western heroism.

The films’ central horrors—the Stranger’s merciless vengeance, the cannibal’s transformative hunger, and the doomed rescue mission into darkness—serve as meditations on violence, communal complicity, and the absence of redemption. They unmask the American West and America itself as terrains haunted by deep, unresolved sins and moral ambiguity. In marrying supernatural and psychological horror, these films offer a complex, layered critique of frontier myth, turning the Western from a tale of conquest into a haunted narrative of trauma, survival, and moral reckoning.

Supernatural vs Psychological Readings

High Plains Drifter uniquely embodies ambiguity between supernatural revenge and psychological torment. The Stranger’s ghostlike qualities and resurrection to avenge his murder firmly anchor a supernatural interpretation. His eerie manifestations—such as the bullwhip’s sound triggering vivid nightmares and his mysterious appearance from the desert heat—signal a spectral force beyond human comprehension. Yet, on a psychological level, the Stranger can be viewed as the materialization of the town’s collective guilt and suppressed trauma. This duality enriches the narrative, allowing viewers to interpret the horror as either literal supernatural vengeance or a psycho-spiritual reckoning of internal moral collapse.

Ravenous blurs supernatural and psychological horror by mixing the tangible terror of cannibalism with metaphysical dread. The figure of Ives carries almost mythic qualities—his charismatic yet monstrous presence suggests an otherworldly evil, a contagion consuming the souls of men. The mountain wilderness functions as a liminal space transcending reality, where madness and primal urges surface. This ambiguity invites readings of the horror as both external supernatural curse and internal psychological disintegration, reflecting survival’s dehumanizing cost amidst isolation and guilt.

Bone Tomahawk grounds itself mostly in realistic terror but invokes mythic supernatural threads through the savage tribe’s almost fantastical menace. Their brutal, ritualized violence carries residues of ancestral curses and primal fears that exceed mere human malevolence. The film explores psychological horror through the characters’ terror and helplessness confronting an unknowable evil, making the wilderness and tribe a metaphor for the abyss of human and historical trauma. Thus, horror emerges as both a tangible threat and a psychological abyss threatening identity and sanity.

This interplay of supernatural and psychological horror amplifies these films’ thematic depth. By refusing to confine horror to one domain, they portray the Western frontier as a space haunted simultaneously by ghosts—whether spiritual, historical, or personal—and inner demons manifesting as guilt, fear, and madness.

Ultimately, horror in these Westerns is not merely a matter of frightening events but a profound engagement with unsettled histories and psyches. This dynamic makes their terror resonate long after the screen fades to black, marking the Western as a genre haunted not only by outlaws and the wilderness but by the specters within us all.

Horror profoundly alters the Western genre’s narrative, revealing it as a cultural wound, a landscape haunted by the ghosts of its own violent history and moral contradictions. By challenging sanitized myths and exposing the fragility beneath civilization’s veneer, Ravenous, Bone Tomahawk, and High Plains Drifter not only frighten but provoke deep reflection on the legacies of violence and the nature of justice itself—capturing the horror at the heart of the American story.