“Memories are meant to fade, Lenny. They’re designed that way for a reason.” — Lornette “Mace” Mason

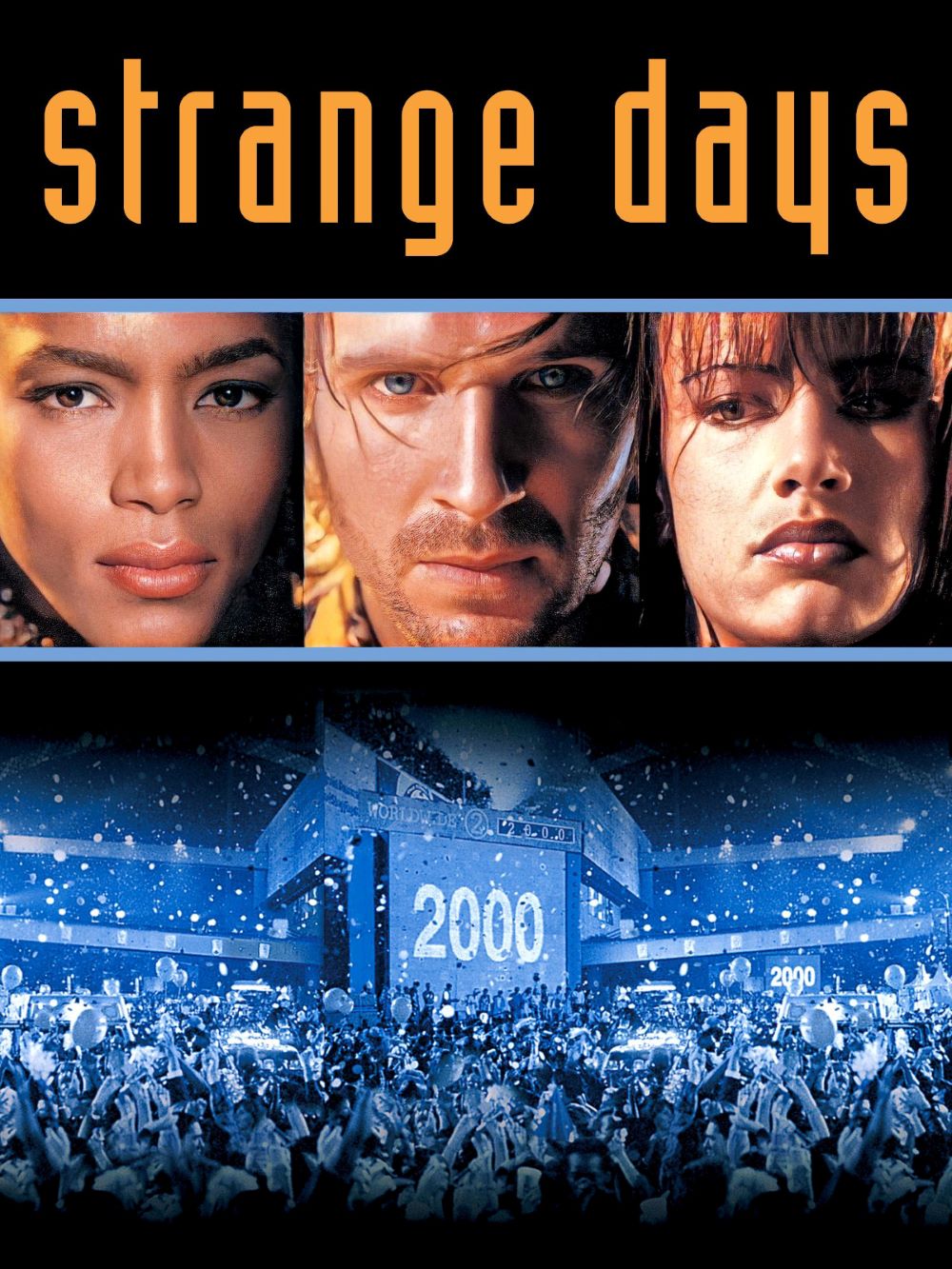

Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days plunges into a gritty, near-future Los Angeles teetering on the edge of the millennium, where illegal “SQUID” technology lets people hijack others’ sensory experiences, fueling a black-market addiction to raw thrills. Released in 1995 with a screenplay by James Cameron and Jay Cocks, the film stars Ralph Fiennes as Lenny Nero, a shady ex-cop dealing these clips amid escalating racial tensions and urban chaos. At over two hours, it mixes cyberpunk visuals with thriller tension, crafting an immersive world that pulses with sensory overload and moral ambiguity.

The story opens with a heart-pounding sequence—a robber’s point-of-view heist captured in one seamless, breathless shot that drops you right into the adrenaline-fueled action, setting a template for the film’s signature subjective dives into chaos. Lenny navigates this underworld, peddling clips of highs and dangers to escape his own regrets, especially over a past love, singer Faith Justin, brought to life by Juliette Lewis with vulnerable intensity that captures the pull of faded dreams. He pulls in his loyal bodyguard Mace, Angela Bassett delivering a fierce, grounded performance, as a mysterious clip hints at deeper corruption involving cops and power players in the city, drawing them into a web of intrigue that tests loyalties amid the neon haze. Bigelow leans into the tech’s seductive pull, where users feel every rush or rush of emotion, blurring lines between observer and participant in uncomfortably real ways that linger long after the credits roll.

Visually, the film explodes off the screen, with cinematographer Matthew Leonetti’s dynamic camera and Bigelow’s high-octane style painting L.A. as a neon-drenched maze of helicopters, crowds, and holographic distractions that feel alive and oppressive. That kinetic opening blends POV chaos with slick editing that amps the disorientation, making every frame pulse with urgency. The world feels authentically grimy and multicultural, alive with New Year’s Eve energy in clubs and streets, evoking millennial anxiety through thumping sound design and distorted audio bleeds that heighten the sensory assault. Bigelow channels her action roots into visceral set pieces that turn the future into something tangible and tense, rewarding close attention to the details that build immersion, from flickering holograms to rain-slicked streets buzzing with tension.

Fiennes captures Lenny’s sleazy charisma perfectly—a sweaty, chain-smoking hustler whose charm masks desperation, keeping him oddly relatable even as his flaws pile up in moments of quiet vulnerability. Bassett dominates as Mace, a tough wheelwoman with unshakeable integrity, her presence anchoring the frenzy and elevating every exchange with quiet strength that cuts through the chaos like a blade. Lewis adds raw edge to Faith, trapped in a web of influence and ambition, her scenes crackling with desperation and fire. Tom Sizemore brings twitchy noir flavor as Max, Lenny’s private investigator buddy who adds layers of unreliable grit to their partnership, his manic energy bouncing off Fiennes in tense, believable banter. The cast meshes well in the overload, though some peripheral figures lean into cyberpunk stereotypes like street dealers and digital oddities, occasionally stretching the vibe thin without fully fleshing out their roles amid the relentless pace.

At its core, Strange Days digs into tech’s grip on empathy in a numb world, where SQUID clips turn voyeurism into full-body complicity, raising tough questions about detachment, consent, and the thrill of borrowed lives. Lenny’s habit of replaying personal moments underscores the addictive pull of reliving the past, turning memory into a dangerous escape that erodes real connections. Bigelow threads in sharp commentary on racism and authority, drawing from real ’90s unrest, with Mace pushing for truth amid systemic shadows in ways that feel urgent and unflinching, her moral compass a steady force against the moral rot. The infamous rape scene stands out as a gut-wrenching pinnacle of this approach, forcing viewers into the perpetrator’s twisted perspective via SQUID playback, amplifying the victim’s terror and the assailant’s depravity to confront voyeuristic horror and power imbalances head-on without pulling punches or easy outs—its raw intensity is jarring, deliberately so, to expose the ethical rot at the tech’s heart. The female-led perspective highlights abuses thoughtfully, adding layers to the spectacle and giving the film a distinctive edge that balances exploitation with unflinching critique.

That said, the film isn’t without bumps, as the plot weaves a tangled web of alliances and betrayals that can feel convoluted under the sensory barrage, occasionally losing focus amid the noise and demanding sharper clarity to match its ambition. Its 145-minute runtime sags midway with Lenny’s brooding and repetitive demos, testing patience before ramping up to its feverish peaks, where the editing could trim some fat for tighter momentum. The climax aims for catharsis amid riots and revelations but lands unevenly, with a hopeful turn that feels rushed or tidy in spots, underplaying certain social threads post-buildup and diluting their harder-hitting potential just when they build to a roar. Some effects show their age, like glitchy clip transitions that disrupt rather than enhance the immersion at times.

Still, these rough edges can’t overshadow the film’s bold highs. Bigelow’s direction thrives on discomfort, using the SQUID concept to mirror how media desensitizes us, making every clip a window into ethical quicksand. The sound design deserves special mention—bass-heavy tracks and visceral screams that bleed from headsets create a claustrophobic intensity, amplifying the tech’s invasive allure. Action beats, from high-speed chases to brutal confrontations, showcase Bigelow’s knack for kinetic choreography, with Bassett’s physicality in the driver’s seat stealing the show. Lenny’s arc, flawed as it is, lands with pathos, his hustler’s denial cracking under pressure to reveal flickers of redemption tied to loyalty and loss.

Strange Days delivers highs that exhilarate and lows that challenge, mirroring its own addictive clips—a raw, uneven ride pulsing with Bigelow’s bold vision that thrives on discomfort and connection. Mace’s decency offers human spark amid the dystopia, balancing provocation with heart in a way that elevates the whole, her bond with Lenny grounding the spectacle in something real. It’s provocative cyberpunk for those craving immersion with bite, a film that doesn’t just show a future but makes you live it, flaws and all, leaving you wired and wary. Fire it up if you’re ready to jack in and feel the rush—just brace for the crash.