“So it’s a fucking coin toss? That’s what 50 billion dollars buys us?” — Secretary of Defense Reid Baker

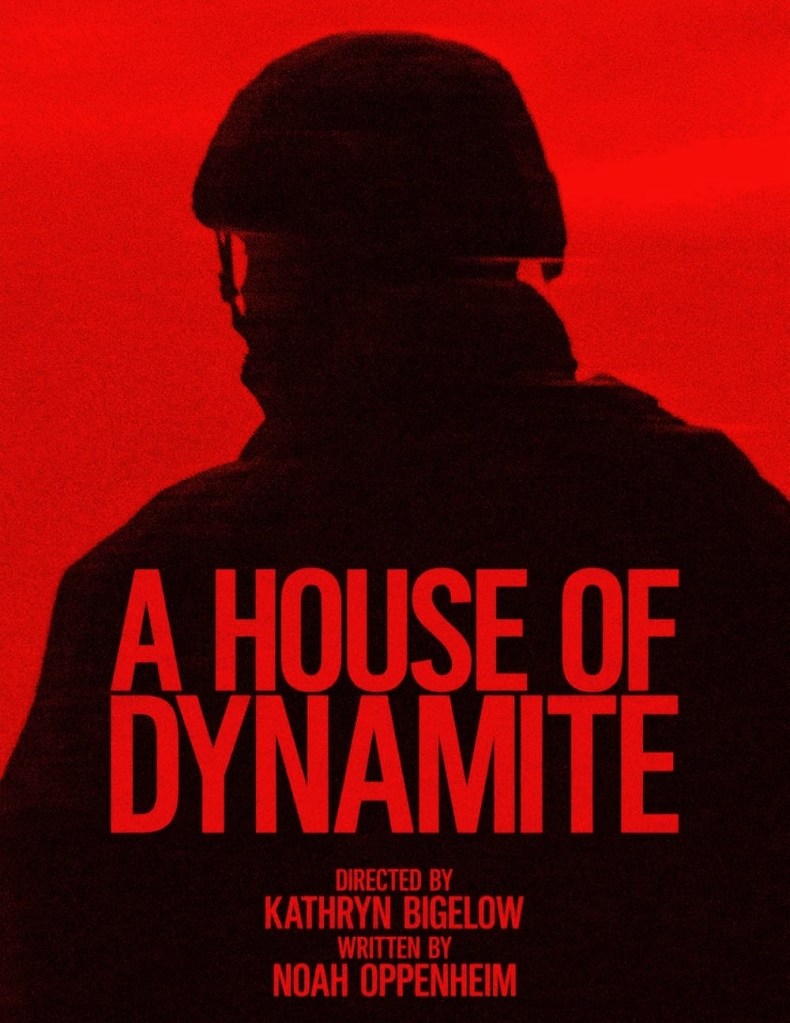

The end of the Cold War was supposed to close a chapter of fear. With the superpowers stepping back from the brink, the world briefly believed it had entered an era of stability. Yet that promise never held. The weapons remained, the rivalries adapted, and the global machinery of deterrence continued to hum beneath the surface. Kathryn Bigelow’s A House of Dynamite faces this reality head-on, transforming the mechanics of modern nuclear defense into something unnervingly human. On the surface, it plays as a high-tension political technothriller, but beneath that precision lies a deeply existential horror film—one built not on shadows or monsters, but on daylight, competence, and the narrow margins of human fallibility.

The premise is piercingly simple. An unidentified missile is detected over the Pacific. Analysts assume it’s a test or a glitch—another false alarm in a world overflowing with them. But within minutes, as conflicting data streams converge, what seemed routine begins to look real. The film unfolds in real time over twenty excruciating minutes, charting the reactions of those charged with interpreting and responding to the potential catastrophe. Bigelow divides the film into three interwoven perspectives: the White House Situation Room, the missile intercept base at Fort Greely, and the President’s mobile command aboard Marine One. The structure allows tension to grow from every direction at once, each perspective magnifying the other until the screen feels ready to collapse under its own pressure.

Capt. Olivia Walker (Rebecca Ferguson), commanding officer of the Situation Room, anchors the story with calm professionalism that gradually frays into disbelief. Ferguson’s performance is clear-eyed and tightly modulated—precise, disciplined, and quietly devastating. She stands as the rational center inside chaos, her composure the last gesture of control in a world that no longer follows reason.

Over her is Adm. Mark Miller (Jason Clarke), Director of the Situation Room, who represents the institutional embodiment of confidence. Clarke plays him with methodical restraint, a man who trusts procedure long after it stops earning trust. Miller’s authority is both comforting and horrifying: a portrait of leadership built on ritual rather than certainty.

At Fort Greely, Anthony Ramos brings an intimate immediacy as the officer charged with the missile intercept. His scenes hum with kinetic dread—the physical execution of decisions made thousands of miles away. Through him, the film captures the most primal kind of fear: acting when hesitation could mean extinction, knowing that success and failure are separated only by chance.

The President, portrayed by Idris Elba, spends much of the crisis in motion—first within the cocoon of the presidential limousine, and later, aboard Marine One as it carves through blinding daylight. Elba gives a performance of subtle, steady erosion. At first, he embodies unshakeable calm, a figure of poise and authority; but as the situation deepens, his steadiness wanes. Words become shorter, pauses longer. Every decision carries consequences too vast for resolution. It is a measured, understated portrait of power giving way to human uncertainty.

Bigelow’s direction is stripped of ornament and focused on precision. Barry Ackroyd’s cinematography heightens the claustrophobia of command centers—the sterile light, the reflective glass, the sense that every surface observes its occupants—while his exterior scenes pierce with harsh brightness, suggesting that no sanctuary exists under full exposure. Kirk Baxter’s editing maintains an unrelenting pulse, cutting with mathematical precision while preserving the eerie stillness of the moments where no one dares to speak.

A House of Dynamite also shows how even with the most competent experts—military, intelligence, and political—working to manage an escalating crisis, there is no path to victory. The professionals at every level stop seeking to prevent the worst and instead focus on saving what they can when the worst becomes inevitable. The film’s scariest revelation is not the potential for destruction, but the paralysis that intelligence creates. If the brightest, most disciplined people in the world cannot find an answer, what happens when power falls into the hands of those less prepared or less rational? In its quiet way, the film poses that question that we see more and more each day on the news and on social media and we are left with silence and realization of the horror of it all.

Despite its precision, the film isn’t without flaws. Bigelow’s triptych structure—cutting between the three perspectives—works brilliantly to escalate tension, yet the repetition of similar beats slightly blunts the impact. Each segment revisits the same crisis rhythms—a data discrepancy, an argument over authority, another uncertain update—sometimes slowing the natural momentum. While the repetition underlines the futility of bureaucratic systems in chaos, the transitions don’t flow as fluidly as the rest of the film’s airtight craftsmanship. The result is a film that is gripping overall, occasionally uneven in rhythm, but never less than absorbing.

When the final minutes arrive, Bigelow declines to deliver resolution. No mushroom clouds, no catharsis. The President sits in Marine One, head down with the weight of the world on his shoulders as he contemplates his options in the Black Book (options in how to retaliate) and knowing that he has no good choices in front of him. The world remains suspended between survival and oblivion, and the silence that follows feels heavier than sound. The ending resists closure because endings, in the nuclear age, are an illusion—the fear continues no matter what happens next.

In a year crowded with strong horror releases—Sinners, Weapons, The Long Walk and Frankenstein among them—A House of Dynamite stands apart. Dressed in the crisp realism of a technothriller, it’s a horror film defined by procedure, light, and silence. Bigelow builds terror from competence, from the steady voices and confident gestures of people trying to manage the unmanageable. This is not the chaos of fiction but the dread of reality, a reminder that the systems meant to preserve and protect might one day fail to deliver on its promise. For all its precision and restraint, A House of Dynamite shakes in the memory long after it ends—the year’s most quietly terrifying film.

Nuclear Close Calls: The situation and question brought up in the film has basis in history as there has been many instances of close calls and false alarms. The film itself doesn’t confirm that the missile detonated, but the implications in past confirmed events just shows how close the world has been to a completed catastrophe.

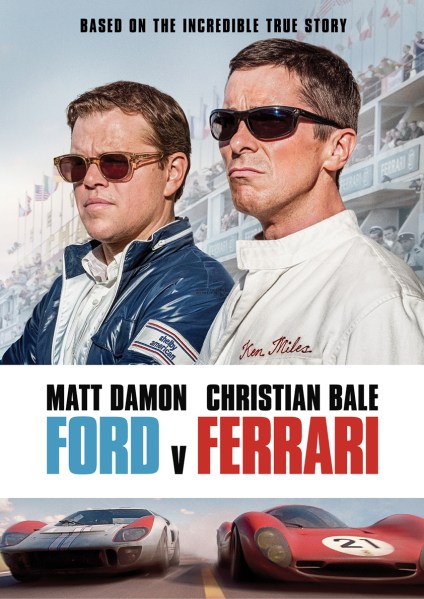

It’s rare for me to say that I enjoyed a film so much that I didn’t want it to end, but James Mangold’s Ford v. Ferrari hits all the right notes. A fantastic cast, impressive visuals on the races, scenes that flow without any time wasted and sound that begs to be heard on a surround system. It’s no surprise that the film earned Four Oscar Nominations – Best Sound Editing, Best Sound Mixing, Best Film Editing and Best Picture, all of which are well deserved. If the lineup this year wasn’t so stacked, I’d say that Ford v Ferrari would score quite a bit. It can go any way, but It may end up like The Shawshank Redemption – A great film that could be eclipsed by giants.

It’s rare for me to say that I enjoyed a film so much that I didn’t want it to end, but James Mangold’s Ford v. Ferrari hits all the right notes. A fantastic cast, impressive visuals on the races, scenes that flow without any time wasted and sound that begs to be heard on a surround system. It’s no surprise that the film earned Four Oscar Nominations – Best Sound Editing, Best Sound Mixing, Best Film Editing and Best Picture, all of which are well deserved. If the lineup this year wasn’t so stacked, I’d say that Ford v Ferrari would score quite a bit. It can go any way, but It may end up like The Shawshank Redemption – A great film that could be eclipsed by giants.