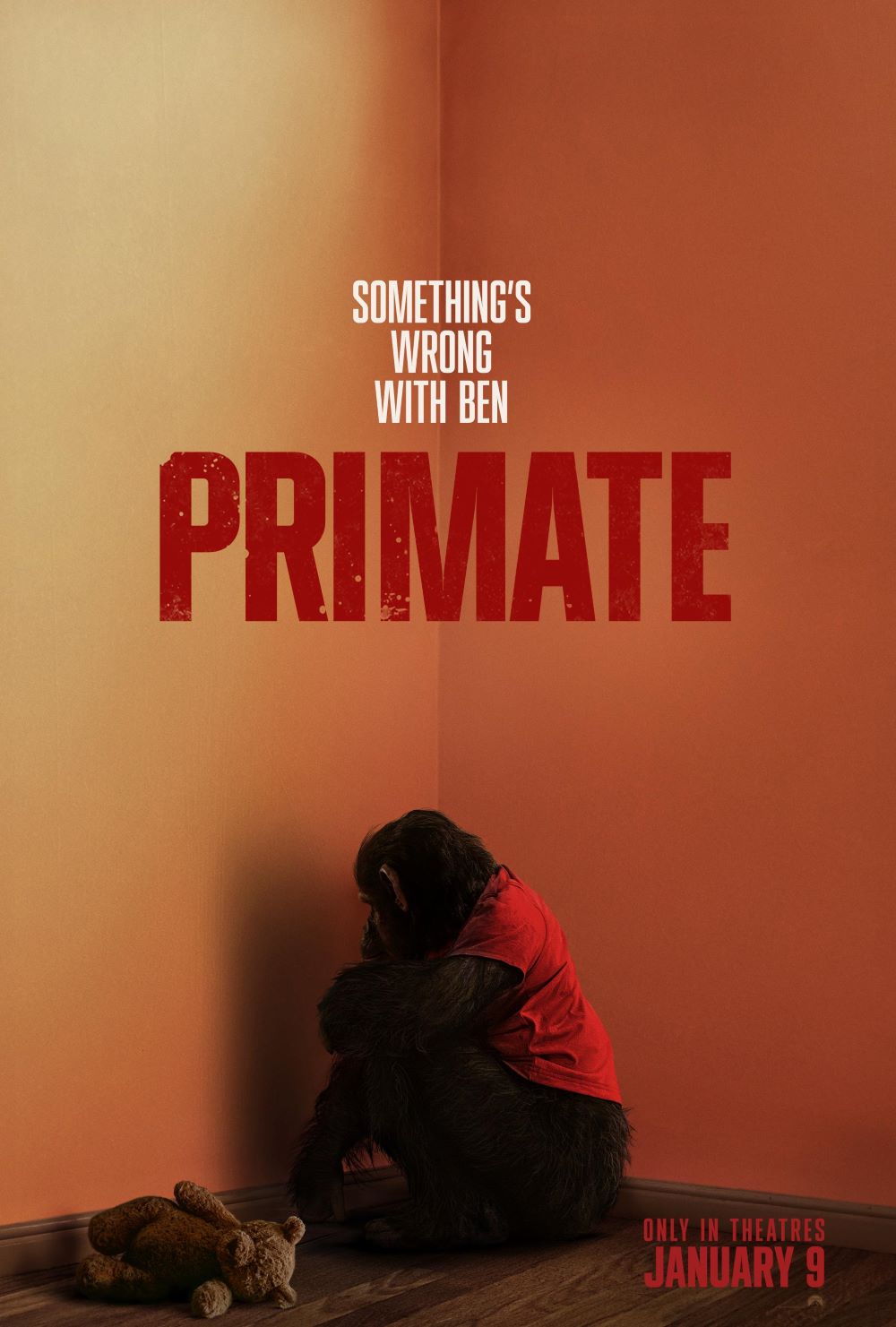

“There’s something wrong with Ben.” — Lucy Pinborough

Primate is the kind of nasty little horror movie that knows exactly what it is: a killer-chimp siege flick with a mean streak, a surprising amount of craft, and just enough emotional texture to keep it from feeling like pure junk food. It is also, very unapologetically, a January-release bloodbath built around one simple promise: you came to watch a chimp rip people apart, and the film is absolutely going to deliver on that.

Set on a remote, luxury house carved into a Hawaiian cliffside, Primate follows Lucy, a college student returning home to her deaf father Adam, younger sister Erin, and Ben—their adopted chimpanzee, who has been taught to communicate using a custom soundboard. The setup leans a bit into family melodrama and awkward-friends-on-vacation vibes: Lucy brings her buddies Kate and Nick, Kate drags along wildcard Hannah, and a pair of party bros, Drew and Brad, orbit the group on the way to a weekend of drinking by the infinity pool. Things tilt into horror when Ben is bitten by a rabid mongoose, starts behaving erratically, and eventually tears the face off the local vet before busting out of his enclosure and turning the house into a kill zone. From there, the movie pretty much drops the pretense of being about anything except survival, creative carnage, and the miserable logistics of trying to outrun a furious primate on a cliff.

Director Johannes Roberts, who previously did 47 Meters Down and The Strangers: Prey at Night, brings that same B-movie efficiency here—minimal fat, fast escalation, and a willingness to lean into the ridiculous without winking too hard. Once Ben escapes, the film basically becomes a series of tightly staged, high-tension set pieces: kids trapped in a pool while a chimp stalks the edge, frantic dashes through glass corridors, and messy, up-close attacks where you really feel the weight and speed of the animal. The pool sequence in particular is a great example of Roberts finding one strong visual idea—humans stranded in water because the predator can’t swim—and milking it for all the dread he can. It’s simple, almost old-fashioned monster-movie blocking, but it works because the geography is clear and the danger feels immediate rather than abstract.

Visually, the film is punching above what you might expect from “rabid chimp horror.” The cliffside house setting gives Roberts and his team a lot to play with: long glass walls, sharp drops, tight stairwells, and that infinity pool hanging over nothing. The camera favors clean, legible compositions instead of frantic shaky-cam, which means when the violence happens, you actually see it—and the movie is proud of that. There’s a grimy 80s-video-store energy to the way kills are framed and lingered on just long enough to be uncomfortable, but not so long that they turn into camp. Adrian Johnston’s synth-heavy score leans into that retro horror vibe too; it buzzes and screeches like someone let a demon loose on a cheap keyboard, and it matches the film’s mix of nasty and playful pretty well.

The real secret weapon here is Ben himself. Rather than going full CGI or trying to work with a real chimp, the production uses a combination of suit performance, animatronics, and careful staging, with Miguel Torres Umba giving the creature its physical personality. The result is surprisingly convincing; there are stretches where it feels like you’re watching a real animal charge people on stairs or slam into doors, which makes the violence land harder. You can tell the effects team put in serious work on the costume and facial mechanics—Ben’s expressions shift from confused, childlike attachment to full-on feral rage, and that emotional readability helps sell him as a character instead of just a prop. Importantly, the film avoids the “PS3 cutscene” problem of bad CG animals, which would have killed the tension immediately.

Performance-wise, this is very much “do your job and don’t get in the way” acting, and that’s mostly a compliment. Johnny Sequoyah makes Lucy feel grounded enough that you buy her as both final girl and guilty older sister who’s been away too long. Troy Kotsur, as Adam, is probably the standout human presence; his scenes use sign language not as a gimmick, but as part of how the family actually lives, and his mixture of vulnerability and stubbornness gives the movie a little heart. The rest of the cast—Jessica Alexander, Victoria Wyant, Gia Hunter, Benjamin Cheng, and the cannon-fodder guys—do what’s asked: they feel like actual young adults rather than complete idiots, which helps when the film needs you to invest in whether they make it out. Nobody is delivering awards-caliber work, but nobody is embarrassing themselves either, and in a film where a chimp tears someone’s jaw off, that’s honestly the sweet spot.

Tonally, Primate walks a line between brutal and darkly funny, and your mileage will depend on how much you enjoy mean-spirited genre films. This is not a movie that’s precious about its characters; the script makes it clear that almost anyone can get obliterated at any moment, and the kill scenes are loud, wet, and often abrupt. There’s a streak of black comedy in how casually some of the deaths happen—a rock to the head here, a shovel to the face there—but Roberts never tips fully into self-parody. At the same time, the film does gesture at something sadder in the idea of a beloved family member suddenly turning dangerous because of a disease, and in the way Lucy has to reconcile her childhood bond with Ben with the reality of what he’s become. The movie doesn’t dig into that theme deeply, but it’s present enough to keep things from feeling completely hollow.

Where Primate stumbles is mostly in its limitations, and whether those feel like flaws or just genre boundaries will depend on what you’re looking for. The script is extremely straightforward: characters have clear, basic motivations, relationships are sketched in a few lines, and then everyone gets funneled into the survival engine. If you want layered character work, subtext about animal ethics, or a big commentary on captivity and communication, this is not that movie, even though the setup with a sign-literate chimp and a linguist mother hints at richer territory. The film also indulges in the usual horror conveniences—texts ignored, warnings missed, people splitting up when they probably shouldn’t—though to its credit, the characters generally behave less stupidly once they understand the situation. And as gnarly as the gore is, the movie’s reliance on shock and escalation can make the back half feel a bit repetitive: Ben appears, someone gets mauled, survivors scramble, repeat.

From an honesty standpoint, Primate is absolutely worth watching if you have a soft spot for creature-features, killer-animal movies, or throwback 80s-style horror that doesn’t pretend to be more than a vicious good time. It’s tightly paced, well shot, and anchored by a genuinely impressive creature performance that justifies the whole exercise. If you’re squeamish about animal violence, or you want your horror to come with metaphor, political commentary, or emotional catharsis, you’ll probably bounce off this pretty quickly. But if you can meet it on its own trashy, committed wavelength, there’s something satisfying about watching a studio-backed film go this hard, this graphically, on such a simple premise. It feels like the kind of bloody, fast-moving B-movie you’d have rented on VHS for a sleepover, only now it’s playing in theaters with a slicker finish and a killer chimp named Ben waiting to wreck your night.