“Those who cling to death; live. Those who cling to life; die.” – Caine

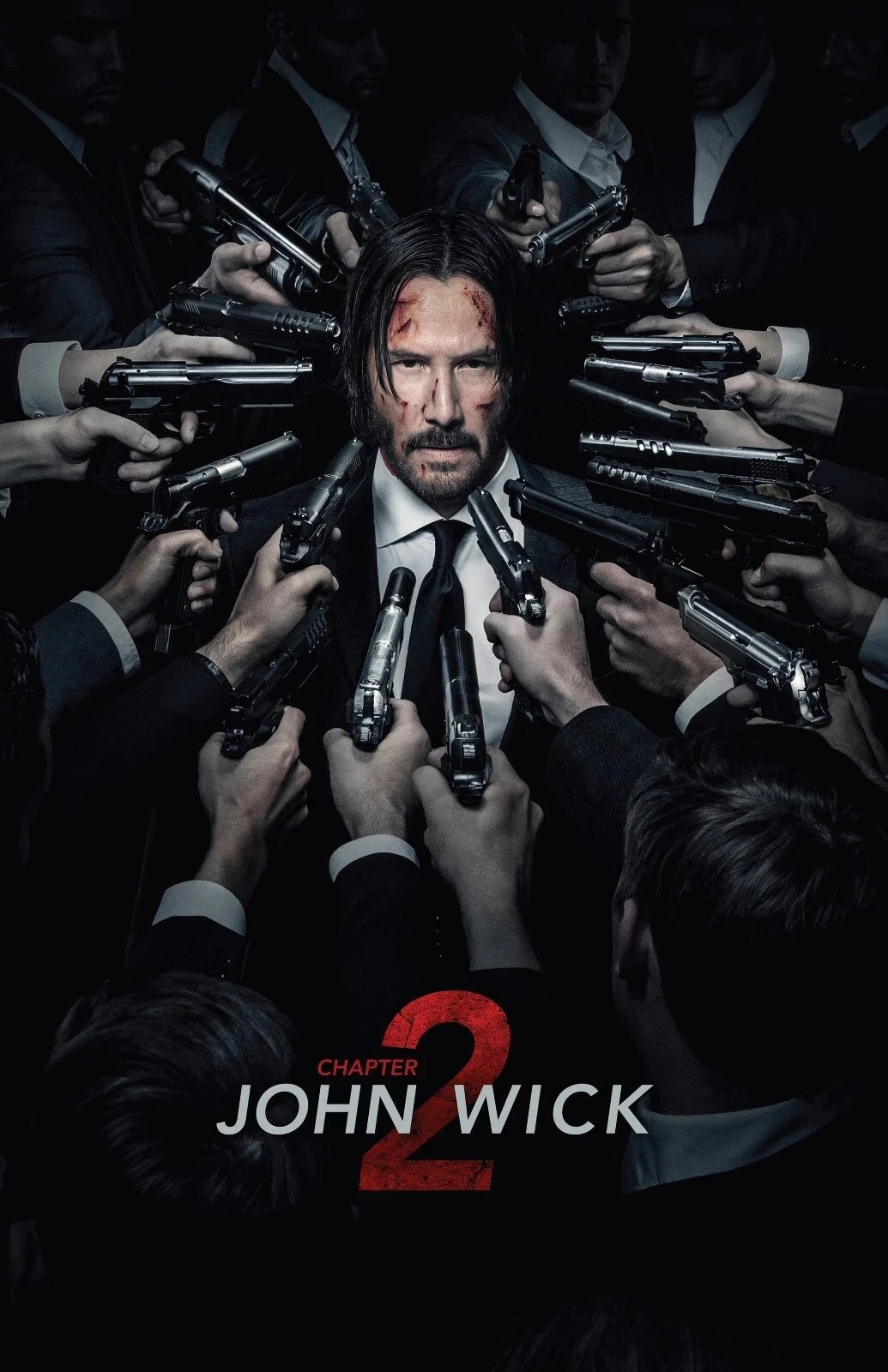

John Wick: Chapter 4 is the kind of action movie that doesn’t just lean into the spotlight—it steps into it, throws a flak vest over its suit, and then spends the next three hours filleting an entire world of assassins with brutal, balletic precision. At this point in the franchise, you’re either all‑in on the rules of the High Table, the Continental, and Wick’s endless mourning for his wife Helen, or you’re just here for the sheer spectacle of seeing Keanu Reeves beat up a continent’s worth of bad guys. The film not only respects that split audience, it tries really hard to satisfy both with a mix of operatic emotion, globe‑trotting locations, and a ridiculous amount of meticulously choreographed carnage.

One of the first things that stands out in John Wick: Chapter 4 is how much the world has expanded since the first film. The script doesn’t reinvent the core idea—Wick wants out, the system wants him broken, and the only way he can be free is by killing his way to the top—but it does layer on new zones, new factions, and a whole supporting cast of assassins who feel like they’re pulled out of their own B‑movies. From Morocco to Berlin, from New York to Paris, the film leans into a kind of hyper‑theatrical world‑building where every hotel lobby, nightclub, and underground fighting arena looks like it was designed by a comic‑book artist with a fetish for brutalism and neon lighting. That’s not a bad thing; it makes the universe feel lived‑in, even if it occasionally borders on self‑parody. The film also shuffles in a few fresh faces that give the usual assassin lineup some new flavors, including Donnie Yen as Caine, the stoic, blind assassin who carries both lethal efficiency and a quiet moral weight; Hiroyuki Sanada as the disciplined Shimazu, whose traditional demeanor and craftsmanship with a sword add a very grounded, almost old‑world element to the chaos; and Rina Sawayama as the high‑ranking assassin Akira, whose presence brings a mix of ruthless professionalism and a genuinely intriguing emotional arc that doesn’t feel like an afterthought.

There’s also Scott Adkins playing against his usual type as Killa Harkan, the head of the German Branch of the High Table, showing up in a surprisingly decent‑looking fat suit that gives him a grotesquely imposing presence while still hinting at the physicality audiences know from his other action roles. The character leans into the film’s tendency toward the theatrical, but he’s not just a walking gag; he fits into the world as one of the more visually exaggerated enforcers of the High Table’s rule. Alongside him, Shamier Anderson brings a lean, relentless energy as the Tracker, Wick’s shadowy, almost dog‑like pursuer whose loyalty to the system makes him more than just another interchangeable goon, while Marko Zaror crops up in the Berlin arena sequences as a brutal, wiry fighter whose style adds yet another distinct flavor to the movie’s unusually diverse fight roster. Taken together, these additions don’t just pad the body count; they give the film a sense that the John Wick universe is big enough to host everyone from classical swordsmen to modern martial‑arts specialists and even a few horror‑movie‑style fanatics, all orbiting the same doomed man.

The villain this time around is the Marquis Vincent Bisset de Gramont, played by Bill Skarsgård, and he’s the kind of High Table emissary who exists purely to make John’s life harder while reminding the audience that the system is more bureaucratic than it is mysterious. He’s got the cold, manipulative air of a corporate executive who’s never actually touched a gun but still has the power to ruin people’s lives on paper. His presence allows the film to spend more time on the politics of the assassin underground, which in turn forces John to pull in a wider network of allies, return favors, and, in a few cases, rebuild old friendships that were already on thin ice. That network includes the Bowery King, Caine, and the rest of the new cast, all of whom add texture to the usual slug‑fest even if the plot’s core emotional arc is still very much about a man who keeps remembering the wife he can’t get back.

Where Chapter 4 really flexes its muscles is in the action, and nowhere is that more obvious than in the extended Paris set‑piece that basically becomes the film’s centerpiece. It starts on the open city streets at night, with Wick already on the move, guns blazing and bodies piling up as the camera weaves through car‑chase energy and close‑quarters shoving. The chaos then escalates when the sequence shifts to the Arc de Triomphe roundabout, where the circular layout turns the whole area into a spinning, three‑dimensional shooting gallery. Cars whip around the monument, bullets ricochet off stone and metal, and the sheer spatial awareness of the choreography makes it feel like you’re watching a real‑time videogame map being systematically cleared in concentric circles, except the “map” is an iconic piece of Parisian infrastructure.

The escalation doesn’t stop there. The action migrates into a mostly empty, half‑abandoned apartment complex that feels like a brutalist concrete maze, each floor and hallway turning into a new arena for sprinting, reloading, and last‑minute dodges. The geography of the building becomes a character of its own, with shots that snake down stairwells, peer through doorways, and frame John as a lone figure ducking and weaving through a vertical death‑trap. It’s inside this apartment complex that the film drops one of its most memorable visual flourishes: a frenetic, prolonged shootout using dragon’s breath shotgun shells—incendiary rounds that send flaming pellets spraying outward—captured from an isometric, top‑down angle that directly evokes the look of indie action‑game favorites like The Hong Kong Massacre. The camera rides high above each room as Wick storms through, watching clusters of fire and bullets explode outward in geometric patterns, turning the interior layout into a living level map. It’s a moment that feels less like traditional cinema and more like a loving, hyper‑stylized homage to the way videogames can turn gunplay into a choreographed light show.

The final stretch of this extended Paris gauntlet is the brutal climb up the Rue Foyatier stairway to the Sacré‑Cœur steps, where the film’s choreographic and camera work reach their most expressionistic peak. The wide shots of Paris looming below, the narrowing of the stairway itself, and the way the camera sometimes drifts into an almost dreamlike, slightly elevated angle all combine to make the sequence feel like an endurance ritual rather than just another fight. By the time Wick reaches the top—after being hurled back down and forced to claw his way up again—the audience feels just as exhausted as he looks, which is exactly the point.

That’s part of what makes the film work when it isn’t just going hand‑to‑hand with you for nearly three hours. Beneath all the shooting and stabbing, John Wick: Chapter 4 is also quietly insistent on the idea that this is a tragedy. John Wick isn’t just a guy who happened to fall into a secret society of killers; he’s a man who has been reshaped by grief, loss, and the realization that every compromise he’s made along the way has only made his cage tighter. The film doesn’t over‑explain this; instead, it lets you watch him limp, cough up blood, and drag his battered frame through one more ambush, as if his body is the only thing strong enough to keep him breathing. The supporting characters—especially those tied to the High Table or to his past, including the newer faces like Caine, Shimazu, Akira, Killa Harkan, the Tracker, and the arena fighters—get a few moments to show that they’re not just cannon fodder, either. They have responsibilities, hierarchies, and codes that clash with the arbitrary cruelty of the Table, even if most of them still end up in the path of Wick’s bullets.

On the flip side, the movie is also unapologetically aware of how silly it is. There’s a knowing winking about the dialogue, the neon‑lit set designs, and the way lines like “You have until sunrise” are delivered with the gravity of a Shakespearean prophecy. The film doesn’t try to make you forget that this is ultimately a high‑end first‑person‑shooter turned into a live‑action ballet. It leans into the absurdity of escalating stakes, the way the world keeps conspiring to throw more and more assassins at John, and the fact that even when he’s bleeding out, he still insists on finishing a fight with a signature flourish. For some viewers, that will feel like a strength, a kind of self‑aware celebration of the genre. For others, it’ll feel like the moment the franchise tips from cool to camp, especially when the pacing starts to drag a bit in the middle section and the mix of formal duels, fat‑suited branch leaders, and endless negotiations begins to feel a little overstuffed.

The film’s length is its biggest liability. At around 169 minutes, John Wick: Chapter 4 is not shy about giving you more than enough time to live inside its world, but it also doesn’t always feel like it needs every last minute. The middle act, in particular, spends a lot of time on formalities, treaties, duels, and metaphysical negotiations with the High Table, which can slow the momentum when what you really want is for John to do another hallway‑fight or another truck‑pile‑up. There are times when the script feels like it’s stretching itself out to keep the spectacle going rather than tightening the storytelling, and that’s when the silliness of it all—like the deliberately over‑the‑top presence of Killa Harkan and the packed gallery of new faces—can start to work against the emotional weight the film is trying to build. A leaner, more ruthless edit would probably make the overall experience feel sharper and more focused.

Still, there’s a lot to admire in what the film manages to pull off. The sound design, the camera work, and the way the choreography is almost always shot in wide, relatively clear takes all combine to make the action feel substantial rather than edited into incomprehensible chaos. The supporting cast—Donnie Yen, Hiroyuki Sanada, Rina Sawayama, Scott Adkins, Shamier Anderson, Marko Zaror, and others—add texture and personality to a world that could otherwise feel like a series of interchangeable goons. They’re not just there to get shot; they’re there to give the film a sense of a larger, more complicated ecosystem of killers, each with their own rules and reasons.

In the end, John Wick: Chapter 4 is less a strict narrative continuation and more of a cinematic endurance event. It doesn’t reinvent the franchise, but it pushes the Wick formula into more extreme, more theatrical, and more emotionally committed territory. It’s messy in places, overstuffed in others, but it also has a few moments of pure, jaw‑dropping action that will probably end up in “best of the decade” lists among genre fans, especially that Paris mega‑set‑piece that starts on open streets, spirals through the Arc de Triomphe, invades an empty apartment complex for that dragon’s‑breath top‑down firefight, and climaxes on the Rue Foyatier stairs. If you’re someone who cares about emotional coherence and tight plotting, the film will probably test your patience. If you’re someone who’s here for the ballet of bullets, the operatic bloodshed, the eccentric new cast, and the sight of Keanu Reeves refusing to stay down no matter how many times the universe tries to kill him, then John Wick: Chapter 4 is a pretty satisfying send‑off—or at least a very loud, very stylish stop on the way there.

Weapons used by John Wick throughout the film

- Glock 34 (TTI Combat Master Package) – His primary pistol early on, including the Morocco sequence against the new Elder and during the Osaka Continental battle.

- Agency Arms Glock 17 – Used by Wick during the garden fight at the Osaka Continental after he takes it off a High Table enforcer.

- TTI Pit Viper – The “hero gun” of the movie, custom‑built for Chapter 4, used heavily in the Paris staircase and duel lead‑up sequences.

- Thompson Center Arms Encore pistol – custom-made single-shot pistols created specifically for the Sacre-Couer duel.

- TTI Dracarys Gen‑12 – The dragon’s‑breath shotgun he grabs during the Paris apartment sequence, used in the isometric top‑down “videogame” style scene.

- Spike’s Tactical Compressor carbine – Used by Wick after he takes it from High Table enforcers during the Osaka Continental fight.

John Wick Franchise (spinoffs)