So, this year I am making a sincere effort to review every film that I see. I know I say that every year but this time, I really mean it.

So, in an effort to catch up, here are four quick reviews of some of the movies that I watched over the past few weeks!

- Crisscross

- Released: 1992

- Directed by Chris Menges

- Starring David Arnott, Goldie Hawn, Arliss Howard, Keith Carradine, James Gammon, Steve Buscemi

An annoying kid named Chris Cross (David Arnott) tells us the story of his life.

In the year 1969, Chris and his mother, Tracy (Goldie Hawn), are living in Key West. While the rest of the country is excitedly watching the first moon landing, Chris and Tracy are just trying to figure out how to survive day-to-day. Tracy tries to keep her son from learning that she’s working as a stripper but, not surprisingly, he eventually finds out. Chris comes across some drugs that are being smuggled into Florida and, wanting to help his mother, he decides to steal them and sell them himself. Complicating matters is the fact that the members of the drug ring (one of whom is played by Steve Buscemi) don’t want the competition. As well, Tracy is now dating Joe (Arliss Howard), who just happens to be an undercover cop. And, finally, making things even more difficult is the fact that Chris just isn’t that smart.

There are actually a lot of good things to be said about Crisscross. The film was directed by the renowned cinematographer, Chris Menges, so it looks great. Both Arliss Howard and Goldie Hawn give sympathetic performances and Keith Carradine has a great cameo as Chris’s spaced out dad. (Traumatized by his experiences in Vietnam, Chris’s Dad left his family and joined a commune.) But, as a character, Chris is almost too stupid to be believed and his overwrought narration doesn’t do the story any good. Directed and written with perhaps a less heavy hand, Crisscross could have been a really good movie but, as it is, it’s merely an interesting misfire.

- The Dust Factory

- Released: 2004

- Directed by Eric Small

- Starring Armin Mueller-Stahl, Hayden Panettiere, Ryan Kelly, Kim Myers, George de la Pena, Michael Angarano, Peter Horton

Ryan (Ryan Kelly) is a teen who stopped speaking after his father died. One day, Ryan falls off a bridge and promptly drowns. However, he’s not quite dead yet! Instead, he’s in The Dust Factory, which is apparently where you go when you’re on the verge of death. It’s a very nice place to hang out while deciding whether you want to leap into the world of the dead or return to the land of the living. Giving Ryan a tour of the Dust Factory is his grandfather (Armin Mueller-Stahl). Suggesting that maybe Ryan should just stay in the Dust Factory forever is a girl named Melanie (Hayden Panettiere). Showing up randomly and acting like a jerk is a character known as The Ringmaster (George De La Pena). Will Ryan choose death or will he return with a new zest for living life? And, even more importantly, will the fact that Ryan’s an unlikely hockey fan somehow play into the film’s climax?

The Dust Factory is the type of unabashedly sentimental and theologically confused film that just drives me crazy. This is one of those films that so indulges every possible cliché that I was shocked to discover that it wasn’t based on some obscure YA tome. I’m sure there’s some people who cry while watching this film but ultimately, it’s about as deep as Facebook meme.

- Gambit

- Released: 2012

- Directed by Michael Hoffman

- Starring Colin Firth, Cameron Diaz, Alan Rickman, Tom Courtenay, Stanley Tucci, Cloris Leachman, Togo Igawa

Harry Deane (Colin Firth) is beleaguered art collector who, for the sake of petty revenge (which, as we all know, is the best type of revenge), tries to trick the snobbish Lord Shabandar (Alan Rickman) into spending a lot of money on a fake Monet. To do this, he will have to team up with both an eccentric art forger (Tom Courtenay) and a Texas rodeo star named PJ Puznowksi (Cameron Diaz). The plan is to claim that PJ inherited the fake Monet from her grandfather who received the painting from Hermann Goering at the end of the World War II and…

Well, listen, let’s stop talking about the plot. This is one of those elaborate heist films where everyone has a silly name and an elaborate back story. It’s also one of those films where everything is overly complicated but not particularly clever. The script was written by the Coen Brothers and, if they had directed it, they would have at least brought some visual flair to the proceedings. Instead, the film was directed by Michael Hoffman and, for the most part, it falls flat. The film is watchable because of the cast but ultimately, it’s not surprising that Gambit never received a theatrical release in the States.

On a personal note, I saw Gambit while Jeff & I were in London last month. So, I’ll always have good memories of watching the movie. So I guess the best way to watch Gambit is when you’re on vacation.

- In The Arms of a Killer

- Released: 1992

- Directed by Robert L. Collins

- Starring Jaclyn Smith, John Spencer, Nina Foch, Gerald S. O’Loughlin, Sandahl Bergman, Linda Dona, Kristoffer Tabori, Michael Nouri

This is the story of two homicide detectives. Detective Vincent Cusack (John Spencer) is tough and cynical and world-weary. Detective Maria Quinn (Jaclyn Smith) is dedicated and still naive about how messy a murder investigation can be when it involves a bunch of Manhattan socialites. A reputed drug dealer is found dead during a party. Apparently, someone intentionally gave him an overdose of heroin. Detective Cusack thinks that the culprit was Dr. Brian Venible (Michael Nouri). Detective Quinn thinks that there has to be some other solution. Complicating things is that Quinn and Venible are … you guessed it … lovers! Is Quinn truly allowing herself to be held in the arms of a killer or is the murderer someone else?

This sound like it should have been a fun movie but instead, it’s all a bit dull. Nouri and Smith have next to no chemistry so you never really care whether the doctor is the killer or not. John Spencer was one of those actors who was pretty much born to play world-weary detectives but, other than his performance, this is pretty forgettable movie.

- Overboard

- Released: 1987

- Directed by Garry Marshall

- Starring Goldie Hawn, Kurt Russell, Edward Herrmann, Katherine Helmond, Roddy McDowall, Michael G. Hagerty, Brian Price, Jared Rushton, Hector Elizondo

When a spoiled heiress named Joanne Slayton (Goldie Hawn) falls off of her luxury yacht, no one seems to care. Even when her husband, Grant (Edward Herrmann), discovers that Joanne was rescued by a garbage boat and that she now has amnesia, he denies knowing who she is. Instead, he takes off with the boat and proceeds to have a good time. The servants (led by Roddy McDowall) who Joanne spent years terrorizing are happy to be away from her. In fact, the only person who does care about Joanne is Dean Proffitt (Kurt Russell). When Dean sees a news report about a woman suffering from amnesia, he heads over to the hospital and declares that Joanne is his wife, Annie.

Convinced that she is Annie, Joanne returns with Dean to his messy house and his four, unruly sons. At first, Dean says that his plan is merely to have Joanne work off some money that she owes him. (Before getting amnesia, Joanne refused to pay Dean for some work he did on her boat.) But soon, Joanne bonds with Dean’s children and she and Dean start to fall in love. However, as both Grant and Dean are about to learn, neither parties nor deception can go on forever…

This is one of those films that’s pretty much saved by movie star charisma. The plot itself is extremely problematic and just about everything that Kurt Russell does in this movie would land him in prison in real life. However, Russell and Goldie Hawn are such a likable couple that the film come close to overcoming its rather creepy premise. Both Russell and Hawn radiate so much charm in this movie that they can make even the stalest of jokes tolerable and it’s always enjoyable to watch Roddy McDowall get snarky. File this one under “Kurt Russell Can Get Away With Almost Anything.”

A remake of Overboard, with the genders swapped, is set to be released in early May.

- Shy People

- Released: 1987

- Directed by Andrei Konchalovsky

- Starring Jill Clayburgh, Barbara Hershey, Martha Plimpton, Merritt Butrick, John Philbin, Don Swayze, Pruitt Taylor Vince, Mare Winningham

Diana Sullivan (Jill Clayburgh) is a writer for Cosmopolitan and she’s got a problem! It turns out that her teenager daughter, Grace (Martha Plimpton), is skipping school and snorting cocaine! OH MY GOD! (And, to think, I thought I was a rebel just because I used to skip Algebra so I could go down to Target and shoplift eyeliner!) Diana knows that she has to do something but what!?

Diana’s solution is to get Grace out of New York. It turns out that Diana has got some distant relatives living in Louisiana bayou. After Cosmo commissions her to write a story about them, Diana grabs Grace and the head down south!

(Because if there’s anything that the readers of Cosmo are going to be interested in, it’s white trash bayou dwellers…)

The only problem is that Ruth (Barbara Hershey) doesn’t want to be interviewed and she’s not particularly happy when Diana and Grace show up. Ruth and her four sons live in the bayous. Three of the sons do whatever Ruth tells them to do. The fourth son is often disobedient so he’s been locked up in a barn. Diana, of course, cannot understand why her relatives aren’t impressed whenever she mentions that she writes for Cosmo. Meanwhile, Grace introduces her cousins to cocaine, which causes them to go crazy. “She’s got some strange white powder!” one of them declares.

So, this is a weird film. On the one hand, you have an immensely talented actress like Jill Clayburgh giving one of the worst performances in cinematic history. (In Clayburgh’s defense, Diana is such a poorly written character that I doubt any actress could have made her in any way believable.) On the other hand, you have Barbara Hershey giving one of the best. As played by Hershey, Ruth is a character who viewers will both fear and admire. Ruth has both the inner strength to survive in the bayou and the type of unsentimental personality that lets you know that you don’t want to cross her. I think we’re supposed to feel that both Diana and Ruth have much to learn from each other but Diana is such an annoying character that you spend most of the movie wishing she would just go away and leave Ruth alone. In the thankless role of Grace, Martha Plimpton brings more depth to the role than was probably present in the script and Don Swayze has a few memorable moments as one of Ruth’s sons. Shy People is full of flaws and never really works as a drama but I’d still recommend watching it for Hershey and Plimpton.

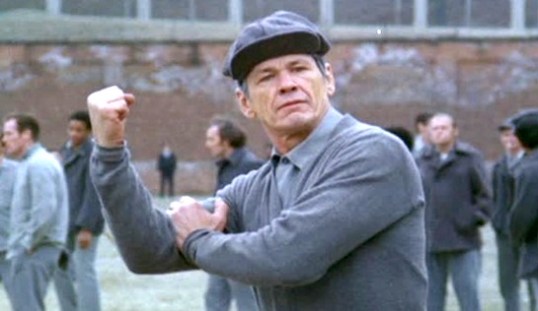

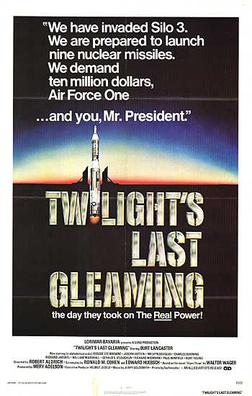

In Montana, four men have infiltrated and taken over a top-secret ICBM complex. Three of the men, Hoxey (William Smith), Garvas (Burt Young), and Powell (Paul Winfield) are considered to be common criminals but their leader is something much different. Until he was court-martialed and sentenced to a military prison, Lawrence Dell (Burt Lancaster) was a respected Air Force general. He even designed the complex that he has now taken over. Dell calls the White House and makes his demands known: he wants ten million dollars and for the President (Charles Durning) to go on television and read the contents of top secret dossier, one that reveals the real reason behind the war in Vietnam. Dell also demands that the President surrender himself so that he can be used as a human shield while Dell and his men make their escape.

In Montana, four men have infiltrated and taken over a top-secret ICBM complex. Three of the men, Hoxey (William Smith), Garvas (Burt Young), and Powell (Paul Winfield) are considered to be common criminals but their leader is something much different. Until he was court-martialed and sentenced to a military prison, Lawrence Dell (Burt Lancaster) was a respected Air Force general. He even designed the complex that he has now taken over. Dell calls the White House and makes his demands known: he wants ten million dollars and for the President (Charles Durning) to go on television and read the contents of top secret dossier, one that reveals the real reason behind the war in Vietnam. Dell also demands that the President surrender himself so that he can be used as a human shield while Dell and his men make their escape.