Based on a novel by James Jones (and technically, a sequel of sorts to From Here To Eternity), 1998’s The Thin Red Line is one of those Best Picture nominees that people seem to either love or hate.

Those who love it point out that the film is visually stunning and that director Terrence Malick takes a unique approach to portraying both the Battle of Guadalcanal and war in general. Whereas Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan told a rather traditional story about the tragedy of war (albeit with much more blood than previous World War II films), The Thin Red Line used the war as a way to consider the innocence of nature and the corrupting influence of mankind. “It’s all about property,” one shell-shocked soldier shouts in the middle of a battle and later, as soldiers die in the tall green grass of the film’s island setting, a baby bird hatches out of an egg. Malick’s film may have been an adaptation of James Jones’s novel but its concerns were all pure Malick, right down to the philosophical voice-overs that were heard throughout the film.

Those who dislike the film point out that it moves at a very deliberate pace and that we don’t really learn much about the characters that the film follows. In fact, with everyone wearing helmets and running through the overgrown grass, it’s often difficult to tell who is who. (One gets the feeling that deliberate on Malick’s point.) They complain that the story is difficult to follow. They point out that the parade of star cameos can be distracting. And they also complain that infantrymen who are constantly having to look out for enemy snipers would not necessarily be having an inner debate about the spirituality of nature.

I will agree that the cameos can be distracting. John Cusack, for example, pops up out of nowhere, plays a major role for a few minutes, and then vanishes from the film. The sight of John Travolta playing an admiral is also a bit distracting, if just because Travolta’s mustache makes him look a bit goofy. George Clooney appears towards the end of the film and delivers a somewhat patronizing lecture to the men under his command. Though his role was apparently meant to be much larger, Adrien Brody ends up two lines of dialogue and eleven minutes of screentime in the film’s final cut.

That said, The Thin Red Line works for me. The film is not meant to be a traditional war film and it’s not necessarily meant to be a realistic recreation of the Battle of Guadalcanal. Instead, it’s a film that plays out like a dream and, when viewed a dream, the philosophical voice overs and the scenes of eerie beauty all make sense. Like the majority of Malick’s films, The Thin Red Line is ultimately a visual poem. The plot is far less important than how the film is put together. It’s a film that immerses you in its world. Even the seeming randomness of the film’s battles and deaths fits together in a definite patten. It’s a Malick film. It’s not for everyone but those who are attuned to Malick’s wavelength will appreciate it even if they don’t understand it.

And while Malick does definitely put an emphasis on the visuals, he still gets some good performances out of his cast. Nick Nolte is chilling as the frustrated officer who has no hesitation about ordering his men to go on a suicide mission. Elias Koteas is genuinely moving as the captain whose military career is ultimately sabotaged by his kind nature. Sean Penn is surprisingly convincing as a cynical sergeant while Jim Caviezel (playing the closest thing the film has to a main character) gets a head start on humanizing messianic characters by playing the most philosophical of the soldiers. Ben Chaplin spends most of his time worrying about his wife back home and his fantasies give us a glimpse of what’s going on in America while its soldiers fight and die overseas.

The Thin Red Line was the first of Terrence Malick’s films to be nominated for Best Picture and it was one of three World War II films to be nominated that year. However, it lost to Shakespeare In Love.

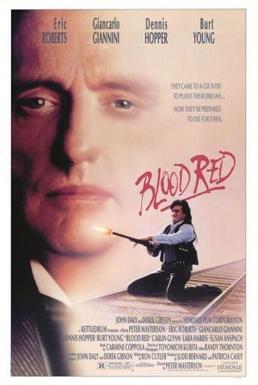

The time is the 1890s. The place is California. Sicilian immigrant Sebastian Collogero (Giancarlo Giannini) has just been sworn in as an American citizen and owns his own vineyard. When Irish immigrant William Bradford Berrigan (Dennis Hopper) demands that Sebastian give up his land so Berrigan run a railroad through it, Sebastian refuses. Berrigan hires a group of thugs led by Andrews (Burt Young) to make Sebastian see the error of his ways. When Sebastian ends up dead, his wayward son, Marco (Eric Roberts), takes up arms and seeks revenge.

The time is the 1890s. The place is California. Sicilian immigrant Sebastian Collogero (Giancarlo Giannini) has just been sworn in as an American citizen and owns his own vineyard. When Irish immigrant William Bradford Berrigan (Dennis Hopper) demands that Sebastian give up his land so Berrigan run a railroad through it, Sebastian refuses. Berrigan hires a group of thugs led by Andrews (Burt Young) to make Sebastian see the error of his ways. When Sebastian ends up dead, his wayward son, Marco (Eric Roberts), takes up arms and seeks revenge.