Taylor Sheridan has become a fairly big part of my life over the last decade. It started when I saw HELL OR HIGH WATER in the movie theater back in 2016. It was one of my favorite movies of the year, and it was written by a guy named Taylor Sheridan. Well, the next year brought us WIND RIVER, which was both written and directed by Taylor Sheridan, and it was one of my favorite movies of 2017. Then came the series YELLOWSTONE, which was created by Taylor Sheridan and began airing in 2018. I didn’t watch the first couple of seasons, but I thought it looked good and even bought the first season on DVD when I saw it for sale at Wal Mart. When my wife Sierra came home from performing her nursely duties at the hospital and told me that everyone was saying that we needed to watch YELLOWSTONE, I informed her that I just so happened to own Season 1 on DVD. So, we popped it in the DVD player, and we were soon obsessed with the world of the Duttons. My wife took special joy in the characters of Beth (Kelly Reilly) and Rip (Cole Hauser), while John Dutton (Kevin Costner) and Rip kept my attention. I’ll admit that it scared me a little bit that Sierra enjoyed Beth so much, and I’m glad to report that, up to this point, she has not started trying to emulate her actions in real life!

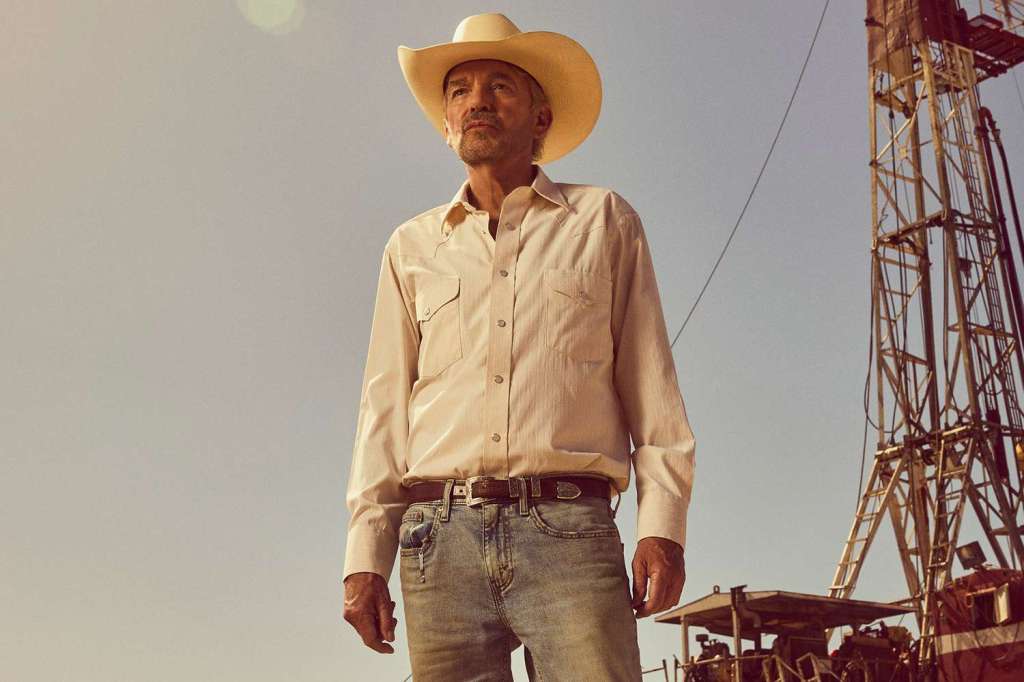

When YELLOWSTONE ended its run at the end of 2024, the Paramount network was putting a major marketing push into their latest “Taylor Sheridan” series, that being LANDMAN, which had started its first season around the same time YELLOWSTONE was wrapping up its final season. I’m a huge fan of actor Billy Bob Thornton, so the fact that he was headlining a series set in Texas oil country automatically piqued my curiosity. Not ready to commit to 10 hours’ worth of LANDMAN episodes quite yet, we put the show on the backburner for a bit, knowing that we could jump in and watch it whenever we wanted to. Well, this past weekend, we got snowed in here in Central Arkansas, so I asked Sierra if she’d like to watch a few episodes of LANDMAN. Needless to say, over the course of the day we watched every episode of Season 1. I really enjoyed the first season and decided to share some of my thoughts with you.

First off, if I’m going to commit to watching 10 hours’ worth of anything, I need to really like at least some of the characters. I don’t just like Billy Bob Thornton’s portrayal of the “Landman” of the title, his Tommy Norris is now one of my favorite characters that he’s ever played. He’s the ultimate realist, because no matter what situation he finds himself in, whether he’s dealing with the head of a drug cartel, the head of his oil company, or his ex-wife, he tackles every situation by uniquely framing the specific issues in a matter of moments and then providing solutions that appeal to his audience’s most base instincts. Alternatively hilarious, serious, heartbreaking and genius, Thornton gives a masterful performance that I don’t think anyone else could have pulled off any more effectively. His ex-wife Angela (Ali Larter) is probably the toughest of all for him to deal with as his own sense of self-preservation seems to go out the window whenever she’s around. Ali Larter’s performance as Angela is loud, brash, attention-seeking, hypersexual, and every so often, just vulnerable enough that you can kind of like her. I think she’s great, and quite sexy, in the role. Michelle Randolph and Jacob Lofland get a lot of screen time in the first season as their children, Ainsley Norris and Cooper Norris. Michelle is cute and spunky, definitely her mother’s daughter, but she also loves her dad so much. I like her. Lofland, who, like Thornton, is from my state of Arkansas, has a meatier role, having to deal with tragedy from the very beginning and then serious family drama as the season plays out. It’s not a showy role, but he does a solid job. The other performance that I really enjoy throughout season 1 comes from Jon Hamm as the head of the oil company, Monty Miller. I kept referring to him as J.R. Ewing as I watched because he’s the big boss. He’s the person that Tommy Norris calls when he can’t solve their problems. Unlike J.R. Ewing, although Miller is a tough businessman, he’s also a committed family man who tries to be there for his wife Cami (Demi Moore) and their daughters when they need him. He is as hard-nosed as it gets in his business dealings, though, and it’s easy to see why he had emerged as the main guy over Tommy. I did want to shout out the actors Colm Feore, James Jordan and Mustafa Speaks as various employees of the oil company who provide different elements of humor and toughness to the proceedings over the course of the season. Finally, as far as the primary cast, while prominently credited throughout the first season, Demi Moore has relatively little to do until the very end of season 1. If you’re a big fan of hers, just know that going in. Her character seems primed to be a big part of season 2, though, so it will be interesting to see where that goes.

Second, like with any popular dramatic TV series, LANDMAN Season 1 contains some storylines that I really enjoy, while there are some that I don’t really care for. Where LANDMAN really works for me is when it features Billy Bob Thornton’s Tommy Norris as a fixer of some sort. It was in these storylines that we get to see his ability to use his intelligence, communication skills, and understanding of human nature to come up with solutions that are best for everyone. It might not always be easy, and he might have to take a beating every now and then, but Tommy knows how to get things done, and the show is at its best when it’s focused on him. We see this throughout season 1 as Norris deals with a variety of cartel henchmen, hotshot attorneys, and unhappy leaseholders in order to advance his company, M-Tex’s interests. There are also a few badass moments when it becomes clear that talking won’t get the job done, and even more direct methods will have to be used to get his point across. This usually happens when Tommy’s feeling the need to protect his children. If there is a weakness to the show, for me, it’s the fact that when Tommy Norris isn’t part of the proceedings, I don’t like it nearly as much. For example, while scenes involving Jacob Lofland’s character, Cooper, and the recently widowed young mother Ariana (Paulina Chavez), whose husband was an employee of the company, ramp up the melodrama, they also take up a lot of time, and I don’t find them very appealing. The same can be said when Ali Larter’s character, Angela, and her daughter Ainsley, decide they’re going to volunteer at a nursing home, and then proceed to hook the residents up with alcohol and even take them to a strip club. While I smiled at some of the proceedings, they weren’t realistic and didn’t really add anything to the story. I even found myself worrying about some of the residents, I mean, I’m sure some of their medication was NOT compatible with tequila! I’m guessing that these quibbles really just come down to a matter of personal preference, as I’m sure there are some who enjoy these moments more than I do. I will admit that these scenes are well-acted and performed even if they’re not advancing my favorite parts of the story.

Overall, I really enjoyed season 1 of LANDMAN, and I’m looking forward to jumping into season 2 soon, which is now streaming. The last couple of episodes of season 1 introduced or elevated some very interesting characters who will have more prominent roles moving forward (played by Andy Garcia and Demi Moore), and peaking ahead, season 2 also appears to have some interesting additions to the cast (I’m looking at you Sam Elliott). I’m looking forward to the next 10 hours of fun!