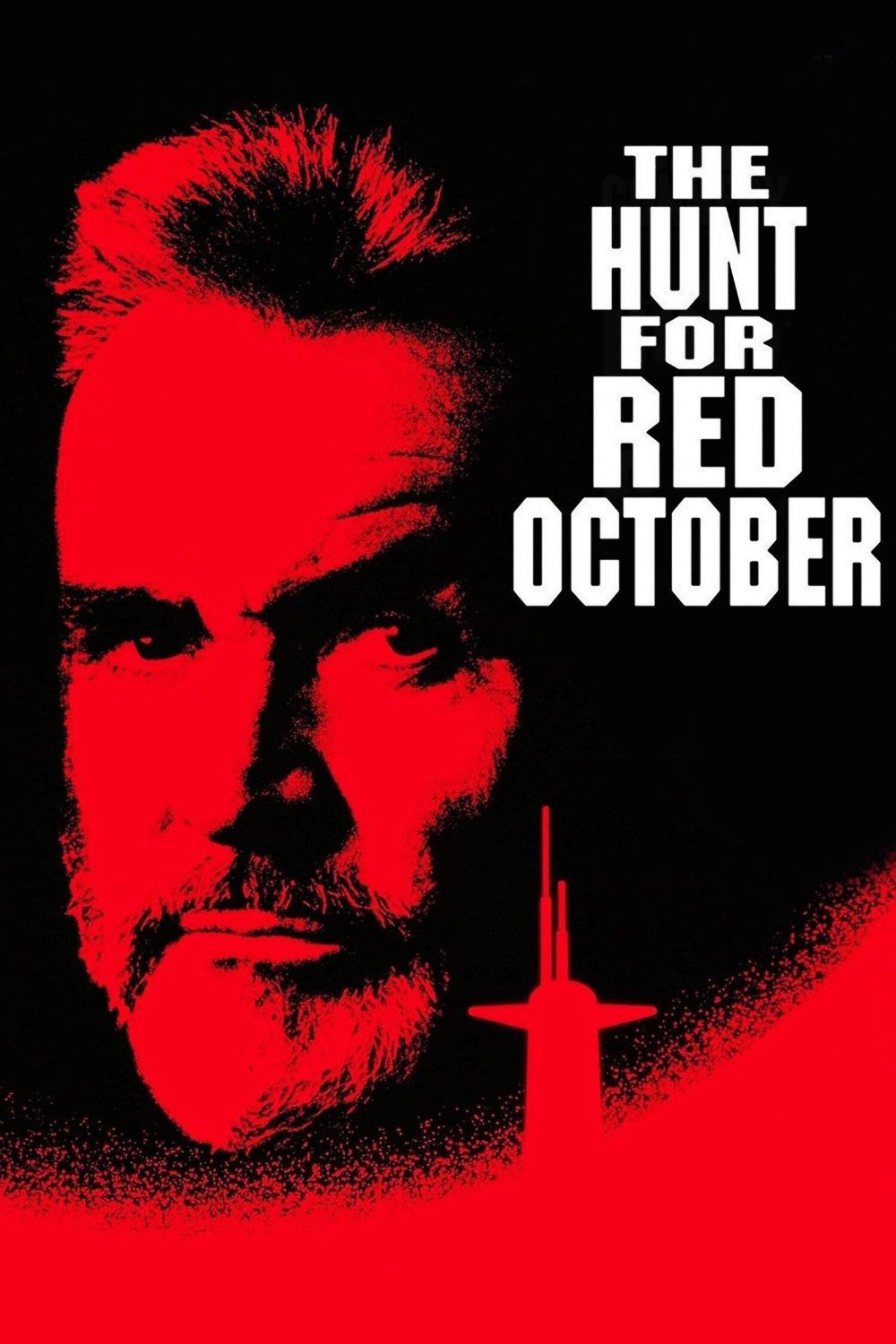

“I’m a politician. Which means that I am a cheat and a liar, and when I’m not kissing babies, I’m stealing their lollipops.” — Dr. Jeffrey Pelt, National Security Advisor

The Hunt for Red October glides into the tail end of Cold War cinema like a stealthy sub cutting through midnight swells, packing a smart mix of spy intrigue and nail-biting underwater showdowns that keep you locked in from the opening credits. Directed by John McTiernan, fresh from helming Die Hard, this 1990 adaptation of Tom Clancy’s doorstopper novel smartly distills pages of naval geekery into a taut, propulsive thriller where Soviet skipper Marko Ramius—Sean Connery in full brooding mode—pilots the formidable Red October, a behemoth sub with a hush-mode propulsion system that ghosts past detection like a shadow in fog.

McTiernan shines in wrangling the script from Clancy’s tech-heavy tome, slicing through the babble to propel the story with crisp momentum and unrelenting suspense, turning potential info-dumps into pulse-quickening beats that hook casual viewers and sub nerds alike. The premise grabs fast: Ramius’s bold maneuvers ignite a transatlantic frenzy, with U.S. and Soviet forces locked in a paranoid standoff over what looks like an imminent crisis. That ’80s-era distrust simmers perfectly here, crammed into a runtime that pulses with fresh urgency decades later, amplified by those dim-lit sub corridors in steely teal tones that squeeze the air right out of the room.

Alec Baldwin embodies Jack Ryan as the reluctant brainiac from CIA desks, sweaty and green around the gills yet armed with instincts that cut through official noise like a periscope through chop. Pulled from family downtime—teddy bear in tow—he injects everyday stakes into the global chessboard, proving heroes don’t need camo or cockiness, just smarts and stubbornness. Connery’s Ramius dominates as a haunted vet with a personal chip on his shoulder, steering a tight-knit officer corps including Sam Neill’s devoted second-in-command, their quiet bonds hinting at deeper loyalties amid the red menace.

Standouts fill the roster seamlessly: James Earl Jones lends gravitas as the steady Admiral Greer backing Ryan’s wild cards; Scott Glenn commands the American hunter sub with laconic steel; Jeffrey Jones brings quirky spark to the sonar savant whose audio tricks flip the script on silence. The dialogue crackles with shorthand lingo and understated jabs, forging a crew dynamic that’s as pressurized as the hull plates, pulling you into hushed command post vibes without a whiff of cheesiness.

McTiernan elevates the genre by leaning on wits over blasts—thrilling pursuits deliver without dominating, letting mind games and split-second calls drive the dread, all while streamlining Clancy’s minutiae into seamless propulsion. Gadgetry gleams without overwhelming: the sub’s whisper-quiet tech sparks clever cat-and-mouse in hazard-filled depths, ramping uncertainty to fever pitch. Pacing builds masterfully from war-room skepticism—Ryan battling brass skepticism—to heart-in-throat ocean dashes, every frame taut as a bowstring. Practical models and effects ground the peril in gritty tangibility, no digital gloss, evoking Ice Station Zebra‘s frosty traps but streamlined into a relentless machine that dodges the older film’s drag. It’s a clinic in balancing spectacle and smarts, where tension coils from isolation’s cruel math: one ping too many, and it’s lights out.

On the eyes and ears front, the movie plunges into submersed nightmare fuel—consoles pulsing crimson in battle stations, scopes piercing mist-shrouded waves, silo bays looming like sleeping leviathans. McTiernan tempers his action flair for thinker-thrills; Basil Poledouris’s great orchestral score surges with iconic power through the chases—those brooding horns, choral swells, and rhythmic pulses echoing engine throbs have etched into legend, pounding your chest like incoming cavitation and elevating every dive. Audio wizardry seals the immersion: hull groans, ping echoes, bubble roars craft a metallic tomb where errors echo eternally. Flaws peek through—early scenes drag with setup chatter, foes skew broad-stroked—but the core hunt erases them, surging to a sharp, satisfying close that nods to Ryan’s budding legend without overplaying the hand.

’90s tentpole lovers and thaw-era history fans find a benchmark here, as the film plays the long con of trust amid torpedoes, fusing bombast with nuance that reboots chase in vain. It bottles superpower jitters spot-on—frantic commands clashing with strike debates—yet softens adversaries via Connery’s world-weary depth and Neill’s subtle conviction. Endless rewatches uncover gems: crew hints dropped early, sonar hacks foreshadowing real tech leaps. Baldwin’s grounded Ryan—chopper-barfing, suit-clashing, chaos-navigating—earns triumphs the hard way, contrasting Das Boot‘s bleak grind with upbeat ingenuity that feels won, not waved. Poledouris’s motifs linger post-credits, a symphonic anchor boosting replay pulls.

Endurance stems from mastering sub-horror’s essence: solitude sharpening choices, where flubs invite apocalypse. Ramius embodies defector realism—war-weary idealist mirroring history’s turncoats—while Clancy’s specs (sub classes, velocities) anchor without anchoring down. McTiernan sidesteps flags; zero flag-waving, pure operator craft in dodges and climactic finesse that blends brains with boom. Quirks delight—the premier’s bluster, aides’ cool calculus—padding a 134-minute gem that exhales you surfacing, amped. Expands on score’s role too: “Hymn to Red October” choral rise mirrors Ramius’s quiet rebellion, threading emotional undercurrents through mechanical mayhem, a Poledouris hallmark outlasting the film.

Bottom line, The Hunt for Red October captivates via cerebral kick—shadow games in fluid physics, intellect over muscle, audacious plays punking empire folly. Sparks post-view chin-strokes on allegiances and risks. Connery’s gravelly “One ping only, Vasily” endures as gold; storm-watch it, trade sofa for sonar station—raw thrill spiked with savvy. Sub saga staple? This silent stalker nails every target.