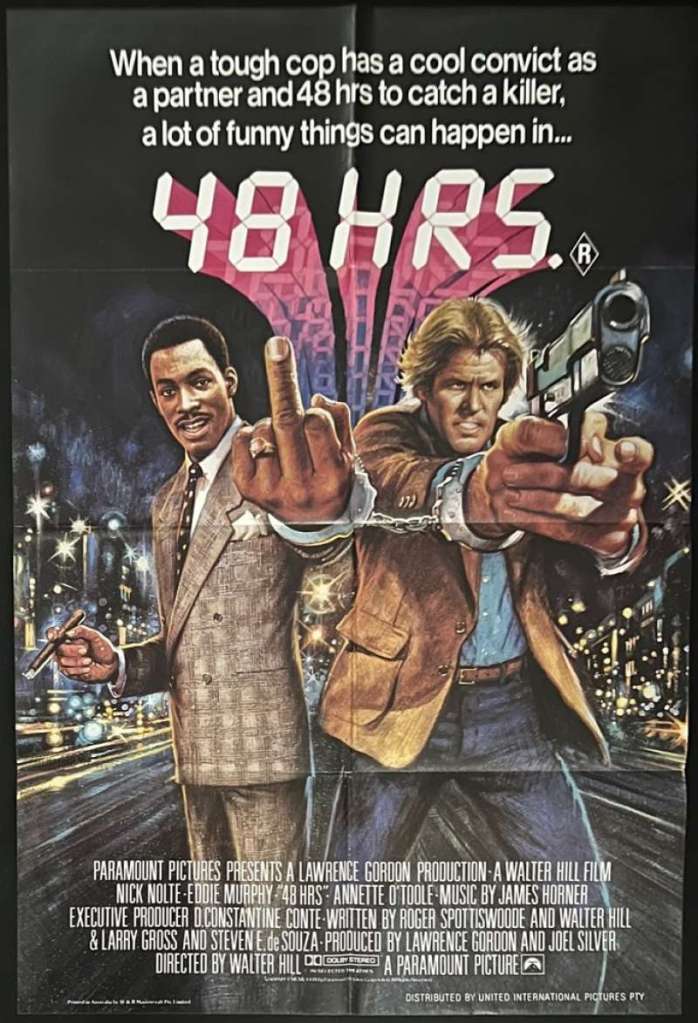

“This ain’t no god damn way to start a partnership.” – Reggie Hammond

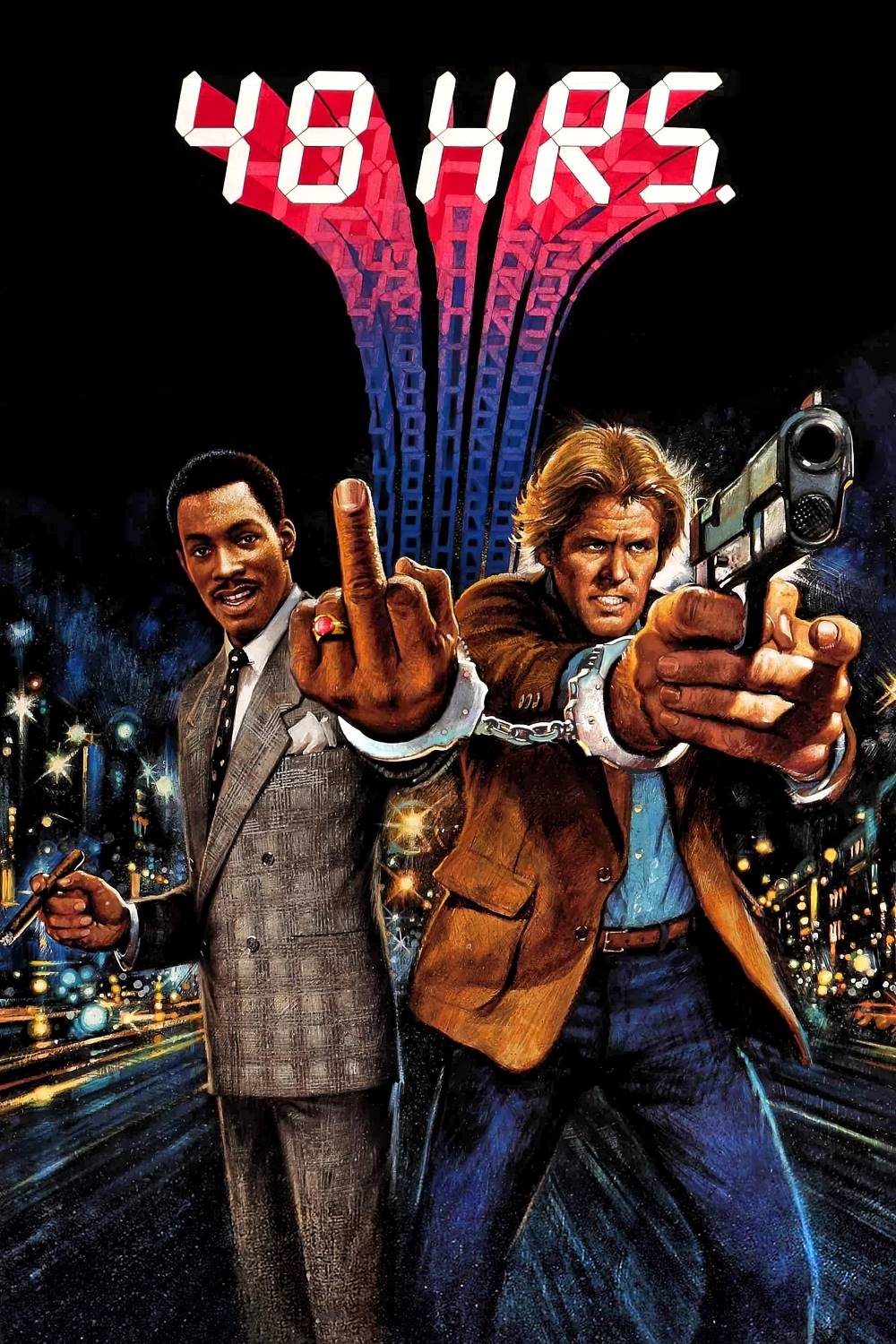

48 Hrs. bursts onto the screen with a gritty prison breakout that sets the stage for chaos in the foggy streets of San Francisco, where a pair of ruthless killers slip away after gunning down a cop’s partner in cold blood. Jack Cates, the surviving detective, is left battered and furious, piecing together a case that points to a slick convict named Reggie Hammond holding the key to the crooks’ whereabouts—and a stash of stolen cash. With time ticking down, Jack pulls strings to get Reggie out on a 48-hour pass, thrusting these two polar opposites into a reluctant alliance that turns the city into their personal battlefield of bullets, banter, and bad blood.

From the jump, Jack comes across as the ultimate rough-around-the-edges cop, nursing a flask under his trench coat, snapping at colleagues, and charging headfirst into danger like a man who’s got nothing left to lose. His apartment is a mess of empty bottles and regret, and his rocky relationship with his girlfriend underscores how the job has chewed him up and spit him out, leaving him more beast than man. Reggie, by contrast, rolls in with street-honed swagger, his prison jumpsuit barely containing the energy of a guy who’s survived by being quicker on his feet and sharper with his mouth than anyone around him. He’s got a girlfriend waiting with that hidden money, and no intention of playing nice with a cop who’s eyeing him like fresh meat.

The beauty of their pairing lies in how the film lets their friction spark from the very first shared car ride, where Jack’s growled commands clash against Reggie’s nonstop ribbing, turning a simple stakeout into a verbal demolition derby. Picture them peeling out after a lead goes south, tires screeching through narrow alleys while Reggie gripes about the beat-up car and Jack slams the dash in frustration—it’s these raw, unscripted-feeling moments that make the movie breathe. As they hit up seedy bars, chase informants through strip joints, and dodge ambushes, the script peels back layers: Jack’s not just a bully, he’s haunted by close calls; Reggie’s bravado masks real fear of ending up dead or broke.

One standout sequence drops them into a hillbilly roadhouse packed with hostile locals, where Reggie grabs the mic for an impromptu takedown that flips the room from menace to mayhem, buying them time while Jack backs him up with sheer firepower. It’s tense, hilarious, and perfectly timed, showing how their skills complement each other—Jack’s brute force meeting Reggie’s silver tongue—in ways neither saw coming. The villains, led by a stone-cold Luther and his trigger-happy sidekick, keep the heat cranked high, popping up for savage hits that leave bodies in the gutter and force the duo to improvise on the fly, like hot-wiring rides or shaking down lowlifes for scraps of intel.

Walter Hill’s direction keeps it all taut and visceral, with handheld cameras capturing the sweat and grime of every punch thrown or shot fired, no glossy filters to soften the blows. The San Francisco backdrop shines through rain-slicked hills, neon-lit dives, and shadowy piers, giving the action a grounded, almost documentary edge that amps up the stakes. Sound design punches too—the roar of engines, the crack of gunfire, the thud of fists—layered over a pulsing ’80s score that shifts from funky grooves during chases to ominous drones in quieter beats, mirroring the push-pull between comedy and threat.

Diving deeper into the characters, Jack’s arc feels earned through small touches: a hesitant phone call to his ex, a flicker of respect when Reggie saves his skin, moments that humanize the hardass without forcing redemption. Reggie evolves too, his initial scam-artist vibe giving way to flashes of loyalty, like when he risks his neck to protect that cash not just for himself, but to build something real outside the walls. Supporting roles flesh out the world—the precinct captain barking orders, the sultry singer tangled with the bad guys, Reggie’s tough-as-nails woman who won’t take guff—but they never overshadow the core duo, serving as sparks for conflict or comic relief.

Pacing-wise, the film rarely pauses for breath, clocking in under two hours yet packing in a full meal of twists, from double-crosses at motels to a frantic foot chase across rooftops that leaves you winded. The 48-hour ticking clock adds urgency without gimmicks, every dead end ramping tension as dawn breaks on their deadline. Humor lands organically too, not from slapstick but from character-driven zingers—Reggie calling out Jack’s outdated tough-guy schtick, Jack grumbling about Reggie’s flashy clothes—keeping the tone light even as blood spills.

Of course, watching through modern eyes, the dialogue packs some era-specific punches, with raw language around race, cops, and crooks that reflects ’80s attitudes head-on, for better or worse. It’s unapologetic, mirroring the film’s macho pulse, but adds texture to the time capsule feel, making replays fascinating for how boldly it leaned into taboos. The women, while fierce in spots, often play second fiddle to the bromance brewing, a hallmark of the genre that 48 Hrs. helped cement before it evolved.

What elevates this beyond standard action fare is how it nails the buddy dynamic’s slow burn: no instant high-fives, just gradual thaw from shared survival, culminating in a dockside finale where alliances solidify amid explosions and last stands. The editing zips between high-octane set pieces and downtime breather scenes, like a roadside diner heart-to-heart that reveals backstories without halting momentum. Cinematography plays with shadows and neon to heighten paranoia, turning everyday spots into pressure cookers.

Influence-wise, you can trace lines straight to later hits—the grizzled vet and smooth-talking newbie formula got refined here, blending Lethal Weapon grit with Beverly Hills Cop wit years ahead of schedule. Performances anchor it all: the leads’ chemistry crackles, carrying weaker beats on sheer charisma, while Hill’s lean style ensures every frame earns its keep. Runtime flies because it’s efficient, no fat, just muscle.

Final stretch ramps to operatic violence on those windswept docks, bullets flying as personal scores settle, leaving our heroes bloodied but bonded in a way that feels hard-won. 48 Hrs. endures as a rowdy blueprint for the genre, blending laughs, thrills, and toughness into a package that’s addictive on first watch and rewarding on revisit. It’s got heart under the bruises, edge in the jokes, and a vibe that’s pure ’80s adrenaline—grab it for a night of no-holds-barred entertainment that still packs a wallop over four decades later.