I noticed that today is Harrison Ford’s 83rd birthday. Like most people born in the early 1970’s, I’m a big fan of Harrison Ford. My formative years included the Star Wars movies, the Indiana Jones movies, and many other great films like BLADE RUNNER (1982) and WITNESS (1984). He would go on to make more classics like THE FUGITIVE (1993) and AIR FORCE ONE (1997) as I got older and moved into adulthood, but one of my personal favorite films starring Harrison Ford is REGARDING HENRY (1991).

In REGARDING HENRY, Harrison Ford stars as Henry Turner, a ruthless bastard, who also happens to be a hugely successful and cutthroat attorney in New York City. This horrific approach to being a human being does seem to provide plenty of money for his wife Sarah (Annette Bening) and his daughter Rachel (Mikki Allen), but you don’t get the feeling there’s that much actual love being shared between the three. Then one night, after another successful day of sticking it to the masses, Henry’s world is turned upside down when he’s shot in the head at the corner convenience store by a guy sticking up the place (John Leguizamo). The bullet to the brain doesn’t kill Henry, but it does leave him with severe brain damage and extremely impaired motor skills. This turns out to be a nice turn of events for Henry, and his family, for several reasons. First, he meets Bradley (Bill Nunn), his physical therapist and all around nice guy, who really helps him get headed back in the right direction in health, and in life, again. Second, he begins to reconnect with his wife who likes this more thoughtful, caring and affectionate version of Henry that seems to be emerging. Finally, he starts to show his daughter some much needed love and attention, rather than just wanting to ship her off to boarding school as quickly as possible. Wouldn’t you know it though, just when things are going so perfect, the sweet, innocent Henry stumbles up some very uncomfortable truths about his former life. Will these revelations upend his new life, or will he be able to move forward with a fresh start and a household filled with love?!!

There are two main reasons that I love REGARDING HENRY. The first reason is undoubtedly the feel-good story at the heart of the film. This is J.J. Abrams second writing credit and his screenplay takes Henry from being an arrogant, selfish jerk who is only interested in his own glorification, to a sweet-natured man of integrity who elevates his wife and his daughter to the prominent positions they rightfully deserve. Is this transformation grounded in reality… no, but I love movies because I want to escape reality and live vicariously through the heroes on the screen. Henry may not be a hero in the same way as Superman, Charles Bronson, or Chow Yun-Fat, but he is someone that I can relate to. I want to be a better dad. I want to be a better husband. I want to be a man of principle and integrity in the workplace. I may not always be perfect, but watching Henry navigate his life and correct past wrongs is very satisfying and uplifting to see. I love the look in the eyes of his wife and daughter as they are so proud of him. I want my family to look at me in that same way. This movie just makes me feel good. When I want realism, I’ll go visit a shrink and watch documentaries about men and women dealing with traumatic brain injuries.

The second reason I love REGARDING HENRY stems from the performances of several of the cast members. Harrison Ford is so good in the title role. His transformation from a cold hearted lawyer to a simple-minded family man is one of those things that could be really bad with the wrong actor, but I’ll gladly follow Ford through the process. He’s believable on both sides, and he has to be for the movie to work. Annette Bening is also great as his wife, Sarah. Her transformation isn’t a physical transformation, but an emotional transformation, and she’s just as convincing. The love she conveys toward Henry as he embraces his new life, followed by the way she plays the scenes when Henry uncovers some of the painful truths of their former life, are actually some of the strongest moments in the film. Finally, I want to give an extra shoutout to Bill Nunn as Bradley, possibly the greatest physical therapist on earth. If dictionaries had pictures, the word “likable” should have a picture of Bill Nunn from REGARDING HENRY. Nunn was a fine character actor, with many credits to his name, but I will never see him in a role that doesn’t take me back to his performance in this film.

Overall, I highly recommend REGARDING HENRY to any person who enjoys a well-made and well-acted feel good story. It’s not the most realistic film in the world, but it’s one that I truly love.

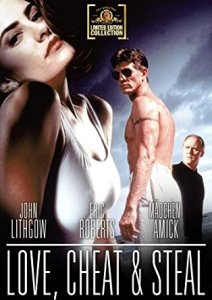

Paul Harrington (John Lithgow) is a wealthy banking consultant who has just married a sexy, younger woman, Lauren (Madchen Amick). Paul thinks that Lauren is perfect but then her brother, Donald (Eric Roberts), shows up. What Paul does not know is that Donald is not actually Lauren’s brother. Instead, Donald is Reno, Lauren’s first husband who she never actually divorced. Reno has just escaped from prison where he was serving time for a crime for which he believes Lauren framed him. While Paul tries to save his father’s failing bank, Reno starts to plan a bank robbery and Lauren tries to balance her old life with Reno with her new life with Paul.

Paul Harrington (John Lithgow) is a wealthy banking consultant who has just married a sexy, younger woman, Lauren (Madchen Amick). Paul thinks that Lauren is perfect but then her brother, Donald (Eric Roberts), shows up. What Paul does not know is that Donald is not actually Lauren’s brother. Instead, Donald is Reno, Lauren’s first husband who she never actually divorced. Reno has just escaped from prison where he was serving time for a crime for which he believes Lauren framed him. While Paul tries to save his father’s failing bank, Reno starts to plan a bank robbery and Lauren tries to balance her old life with Reno with her new life with Paul.