Private Lessons is that kind of early ’80s sex comedy that feels like a time capsule from when movies could get away with stuff that would never fly today. It’s got this awkward charm mixed with some seriously questionable choices, centering on a horny teenager named Philly who gets schooled in the ways of love by his family’s sultry French housekeeper. The film tries to play it all for laughs and titillation, but it lands somewhere between guilty pleasure and uncomfortable relic.

Philly, played by Eric Brown, is your classic 15-year-old rich kid left home alone for the summer in a sprawling Albuquerque mansion while his dad jets off on business. Dad hires Nicole, this alluring European housekeeper portrayed by Sylvia Kristel—yeah, the Emmanuelle star herself—to keep an eye on things, along with the sleazy chauffeur Lester, brought to life by Howard Hesseman in full sleazeball mode. From the jump, Philly’s got a massive crush on Nicole; he’s peeping through keyholes and fumbling over his words whenever she’s around. It’s all very American Pie before American Pie existed, but with a Euro-sex vibe courtesy of Kristel’s effortless sensuality. She catches him spying one night, strips down without a care, and invites him to touch—Philly bolts like his pants are on fire. You can’t help but chuckle at his panic; Brown’s wide-eyed innocence sells it without overplaying the hand.

The setup builds slowly, which is both a strength and a drag. Philly spills the beans to his buddy Sherman, played with manic energy by Patrick Piccininni, who turns every conversation into a roast session about Philly’s virginity. Their banter is some of the film’s highlights—raw, boyish ribbing that feels authentic to awkward teen friendships. Nicole keeps pushing the envelope: a steamy makeout in a dark movie theater, a goodnight kiss that nearly melts the screen, and finally, a fancy French dinner date where they seal the deal back home. Kristel owns these scenes; her Nicole isn’t just a seductress, she’s got this playful confidence that makes the slow seduction believable. The sex scene itself is tame by today’s standards—soft-focus, lots of sighs—but it’s handled with a wink, pretending to be shocking while delivering the era’s softcore goods.

But here’s where Private Lessons swerves into darker territory and kinda loses its footing. Midway through their romp, Nicole fakes a heart attack and “dies” right on top of Philly. Freaked out, he confesses to Lester, who smells opportunity. Turns out, the chauffeur’s been blackmailing Nicole over her immigration status and hatches a scheme to pin her “murder” on Philly, forcing the kid to cough up a chunk of his trust fund to cover it up. They bury a dummy in the desert, and Lester plays the concerned adult while pocketing the cash. It’s a twist that amps up the stakes, but it also shifts the tone from fluffy comedy to something creepier, leaning hard into moral panic territory. Hesseman chews the scenery as Lester, all smarmy grins and side-eye; he’s the perfect villain you love to hate, but the plot machinations feel forced, like the writers ran out of seduction gags and needed conflict.

Nicole, developing real feelings for Philly amid the con, has a change of heart and spills the truth. Together, they rope in Philly’s tennis coach—Ed Begley Jr. in a quick but fun bit—to impersonate a cop and scare Lester straight. The bad guy panics, gets nabbed trying to flee with the money, and everyone agrees to a truce: no one rats anyone out. Nicole’s “child molestation” (the film’s own loaded term for her role in seducing a minor) and immigration issues stay buried, Lester technically keeps his job, and Nicole splits before Dad returns. It’s a tidy wrap-up that dodges real consequences, which fits the film’s escapist fantasy but leaves a sour taste ethically. The romance fizzles without much payoff; you half-expect a heartfelt goodbye, but it’s more pragmatic than emotional.

Tonally, Private Lessons is all over the map. The first half thrives on its lighthearted horniness—Philly’s fumbling advances, Nicole’s teasing allure, and a very of-its-time soundtrack that pumps up the montages. It’s got that innocent raunchiness of films like Porky’s, where sex is the big mystery and everyone’s in on the joke. Brown holds his own as the lead; at 15, he’s convincingly flustered yet game, making Philly relatable rather than cartoonish. Kristel brings actual star power, turning what could be a one-note vixen into someone with hints of depth—her chemistry with Brown sparks genuine warmth amid the sleaze. Hesseman leans into Lester’s slimeball energy, turning every scene with him into a mix of funny and gross.

That said, the film’s not without flaws, and they’re glaring by modern eyes. The premise is straight-up predatory: a grown woman systematically grooming an underage boy, played for comedy without much self-awareness. It’s the male version of Lolita, but without any critique—instead of examining the situation, it just sort of grins and shrugs. The blackmail plot tries to add intrigue but mostly undermines the fun, turning Nicole from free spirit to reluctant crook. Pacing drags in spots; the relatively short runtime still feels stretched when the seduction stalls so the script can set up the con. And the ending? It papers over everything with a shrug, letting all parties walk free like it’s no big deal. The whole thing feels very much like a product of a moment when taboo could be turned into box-office bait without much pushback.

Visually, it’s a product of its time: glossy ’80s cinematography, plenty of skin but no hardcore edge, and that mansion setting screaming wealth fantasy. Director Alan Myerson keeps it breezy, never letting the comedy get too mean-spirited until Lester’s scheme really kicks in. The score and song choices nail the vibe—upbeat for the flirtations, a bit more tense for the con, always keeping things light even when the story goes to shadier places. It very much feels like something that would play late at night on cable and stick in your memory more as a vibe than as a fully coherent film.

Does it hold up? Kind of, if you’re in a nostalgic mood or digging for ’80s cheese. It’s honest about teen lust without being judgmental, and the performances carry the silly plot. But the power imbalance and the underage angle make it tough to fully endorse—watch with that lens, and it’s more cringe than chuckle. Still, for what it is—a raunchy romp with a surprisingly soft center—Private Lessons delivers just enough to warrant a spin on a bored night. Eric Brown and Sylvia Kristel do a lot of heavy lifting; without their chemistry, this would be forgettable smut instead of a strangely endearing, if deeply problematic, relic. If you’re into retro sex comedies like My Tutor or Zapped!, this one sits comfortably in that same dusty corner of the genre, flaws and all, as a snapshot of looser times that’s best taken with a big grain of salt.

Previous Guilty Pleasures

- Half-Baked

- Save The Last Dance

- Every Rose Has Its Thorns

- The Jeremy Kyle Show

- Invasion USA

- The Golden Child

- Final Destination 2

- Paparazzi

- The Principal

- The Substitute

- Terror In The Family

- Pandorum

- Lambada

- Fear

- Cocktail

- Keep Off The Grass

- Girls, Girls, Girls

- Class

- Tart

- King Kong vs. Godzilla

- Hawk the Slayer

- Battle Beyond the Stars

- Meridian

- Walk of Shame

- From Justin To Kelly

- Project Greenlight

- Sex Decoy: Love Stings

- Swimfan

- On the Line

- Wolfen

- Hail Caesar!

- It’s So Cold In The D

- In the Mix

- Healed By Grace

- Valley of the Dolls

- The Legend of Billie Jean

- Death Wish

- Shipping Wars

- Ghost Whisperer

- Parking Wars

- The Dead Are After Me

- Harper’s Island

- The Resurrection of Gavin Stone

- Paranormal State

- Utopia

- Bar Rescue

- The Powers of Matthew Star

- Spiker

- Heavenly Bodies

- Maid in Manhattan

- Rage and Honor

- Saved By The Bell 3. 21 “No Hope With Dope”

- Happy Gilmore

- Solarbabies

- The Dawn of Correction

- Once You Understand

- The Voyeurs

- Robot Jox

- Teen Wolf

- The Running Man

- Double Dragon

- Backtrack

- Julie and Jack

- Karate Warrior

- Invaders From Mars

- Cloverfield

- Aerobicide

- Blood Harvest

- Shocking Dark

- Face The Truth

- Submerged

- The Canyons

- Days of Thunder

- Van Helsing

- The Night Comes for Us

- Code of Silence

- Captain Ron

- Armageddon

- Kate’s Secret

- Point Break

- The Replacements

- The Shadow

- Meteor

- Last Action Hero

- Attack of the Killer Tomatoes

- The Horror at 37,000 Feet

- The ‘Burbs

- Lifeforce

- Highschool of the Dead

- Ice Station Zebra

- No One Lives

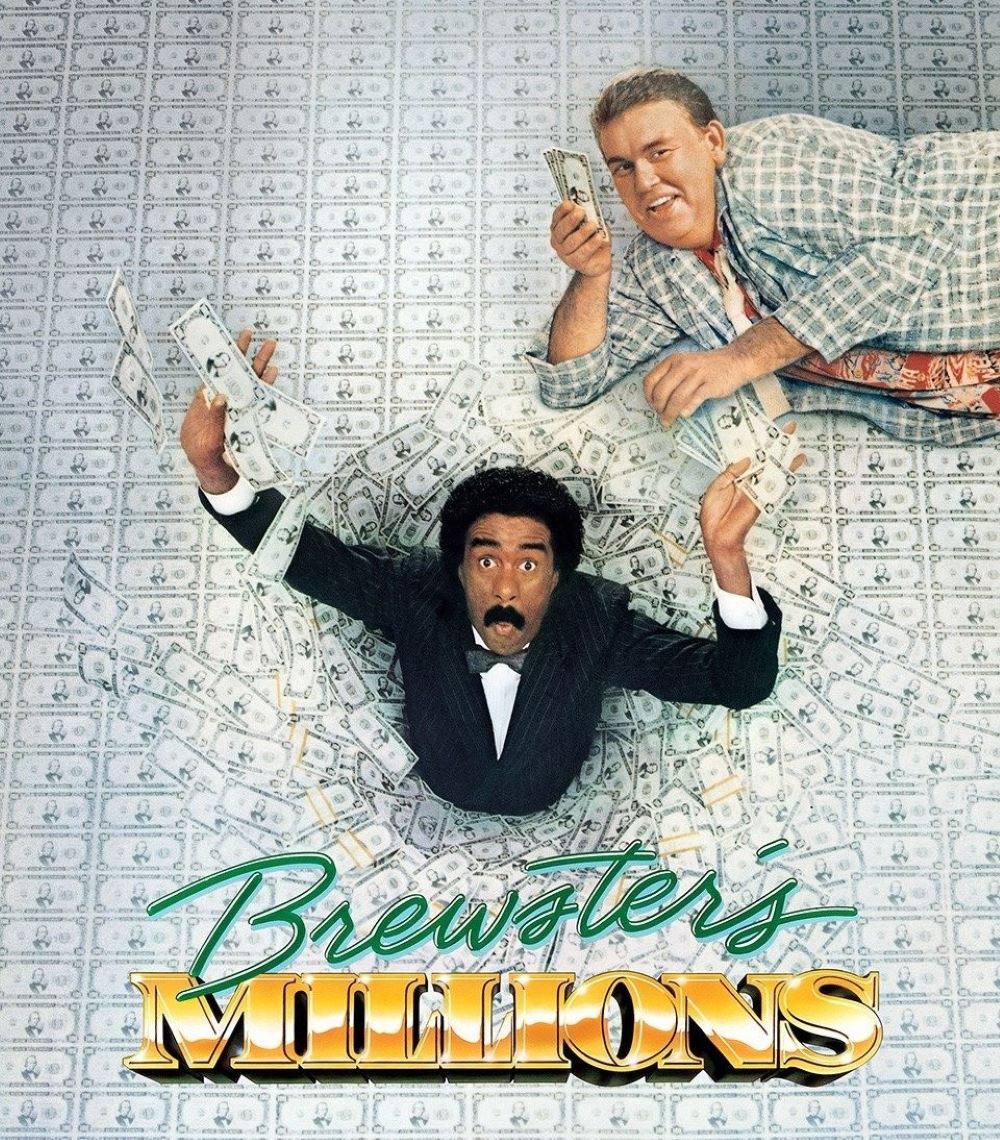

- Brewster’s Millions

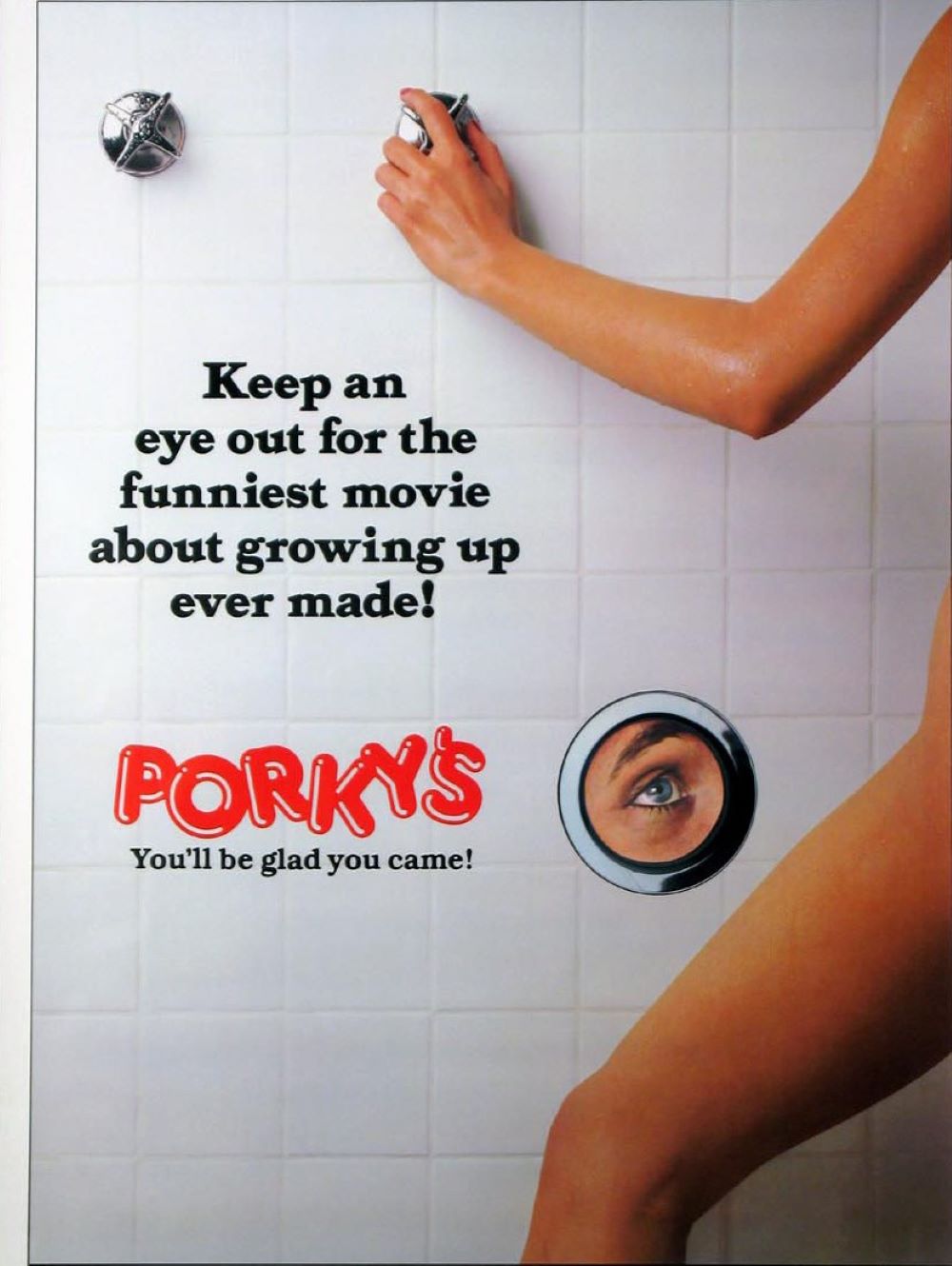

- Porky’s

- Revenge of the Nerds

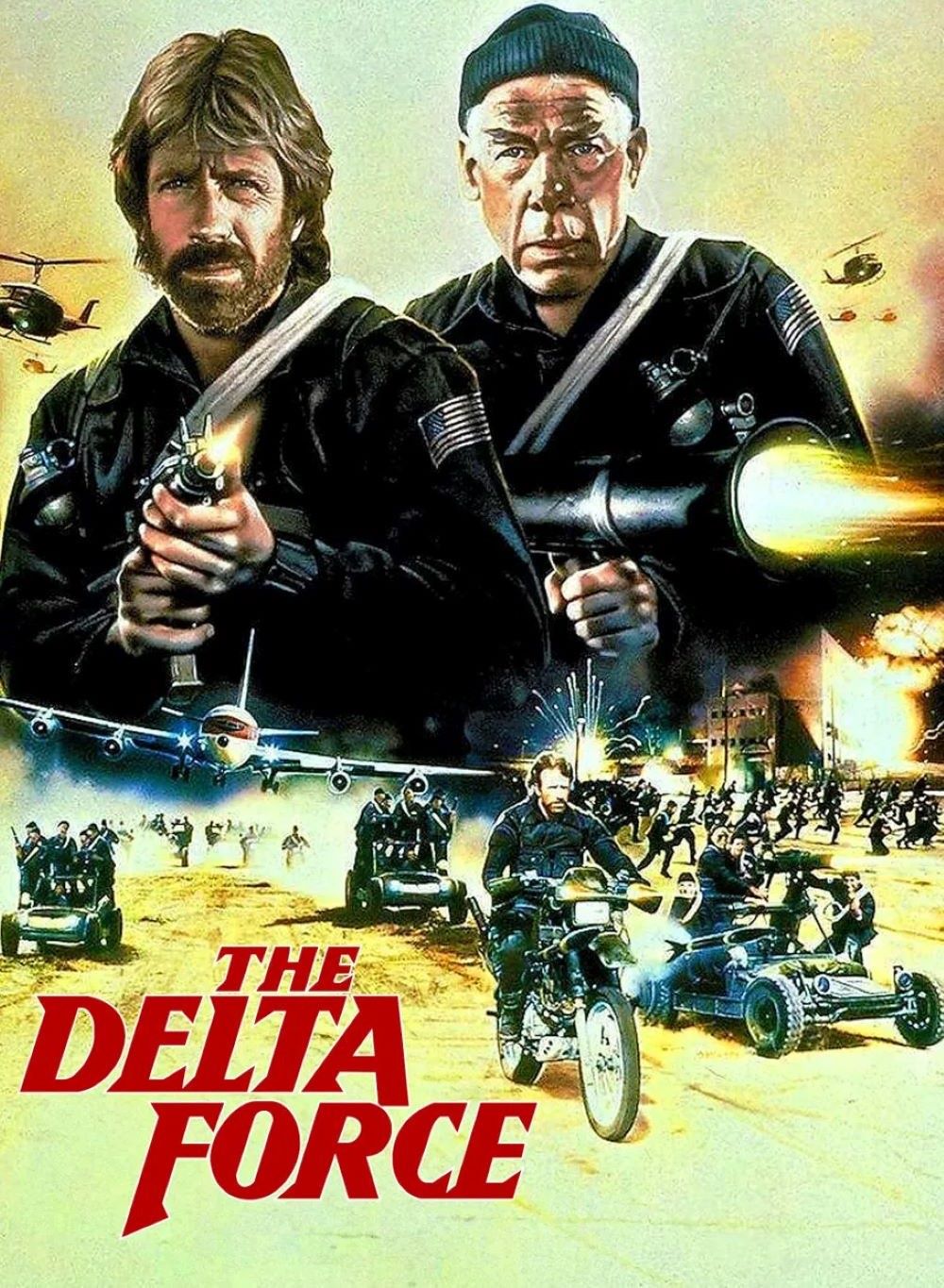

- The Delta Force

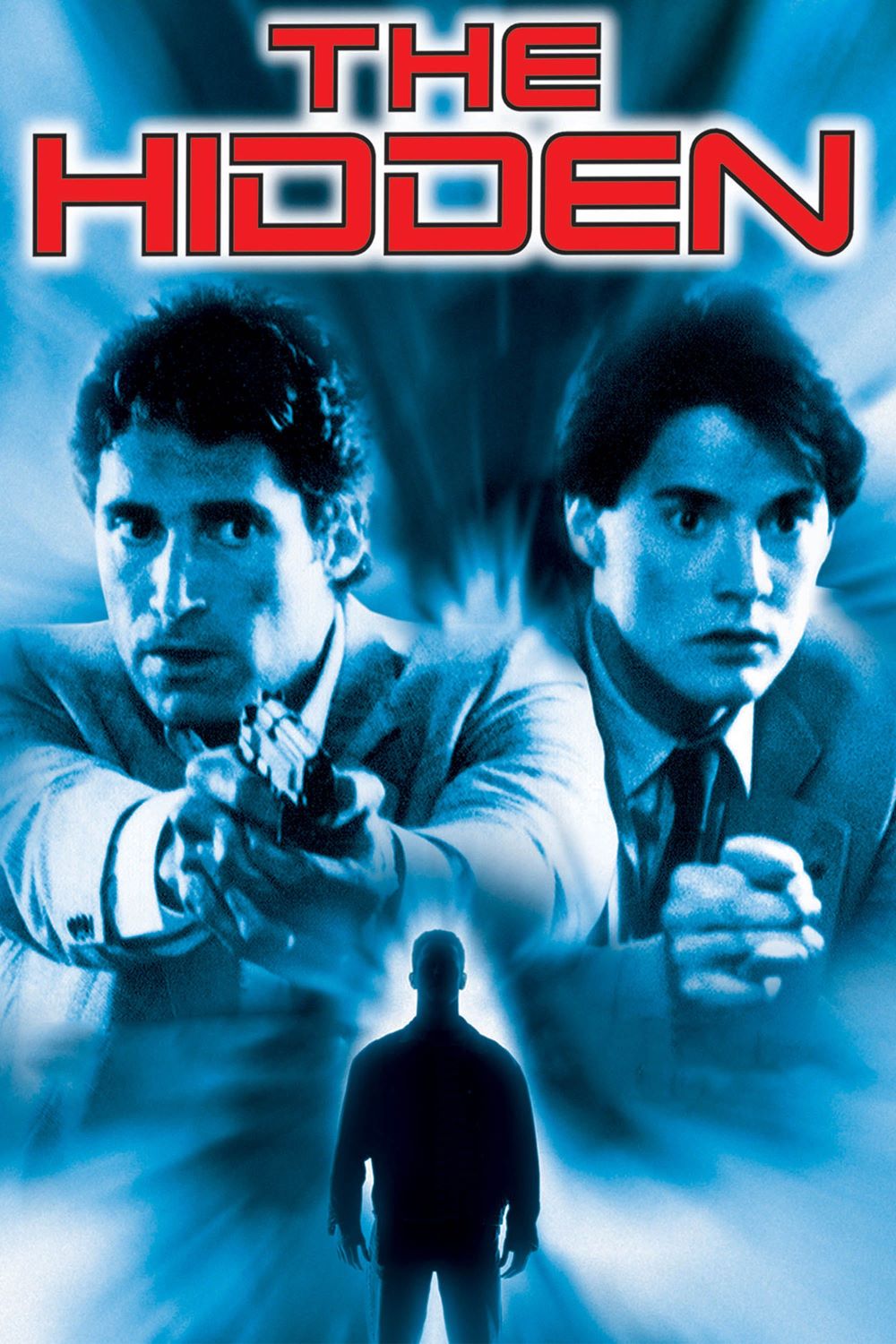

- The Hidden

- Roller Boogie

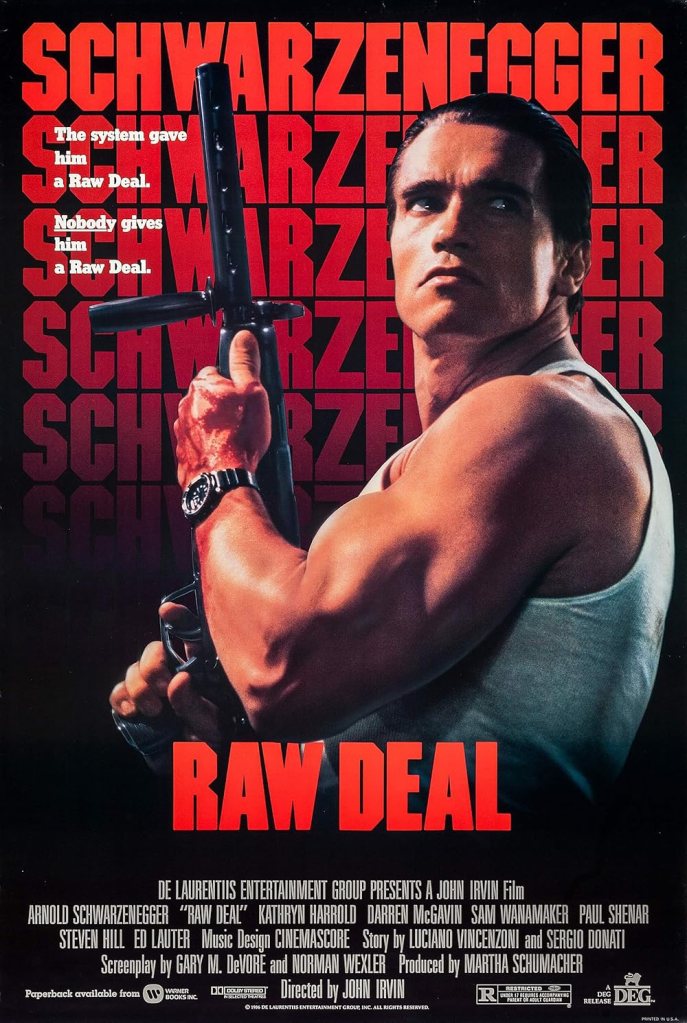

- Raw Deal

- Death Merchant Series

- Ski Patrol

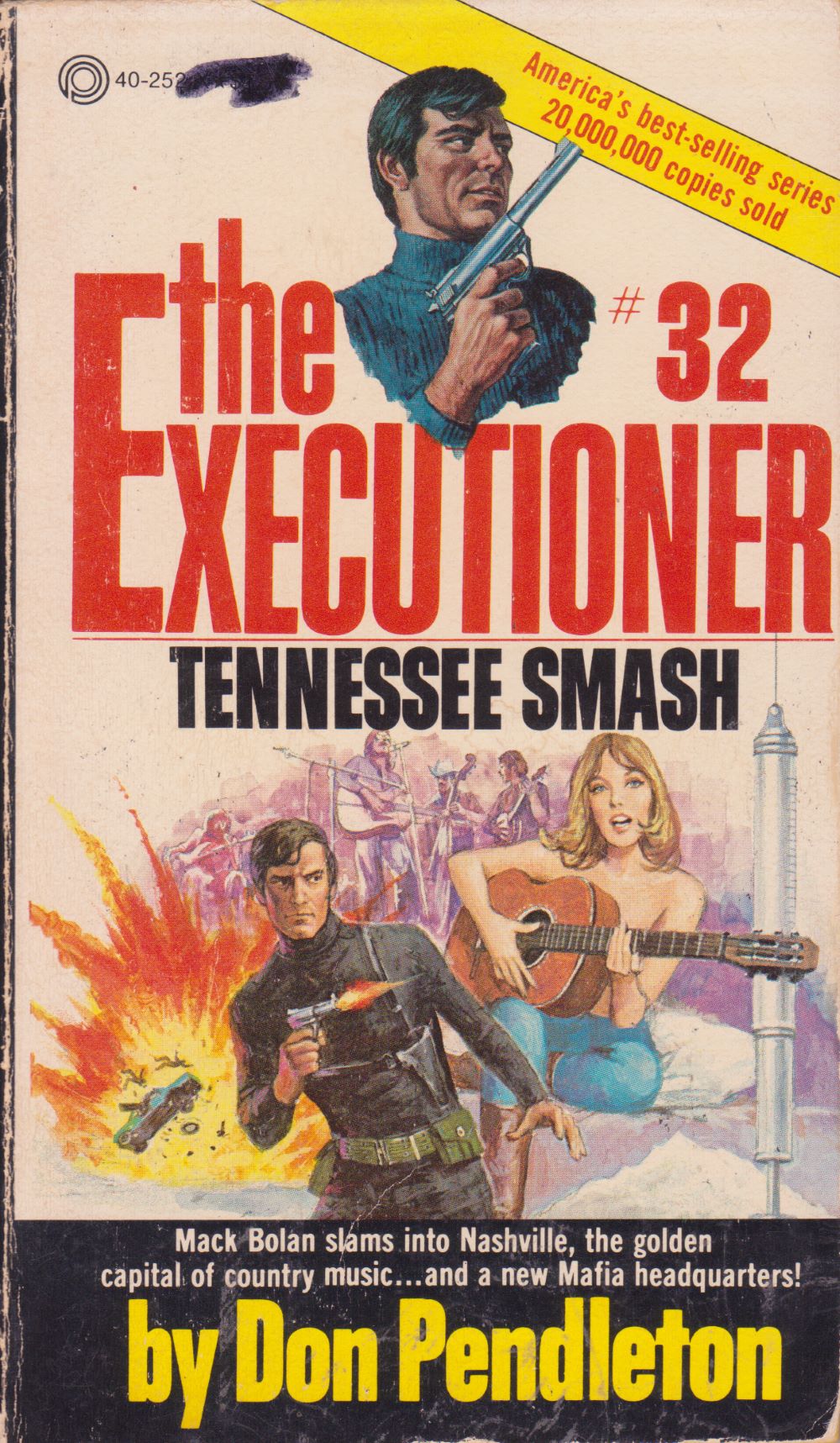

- The Executioner Series

- The Destroyer Series