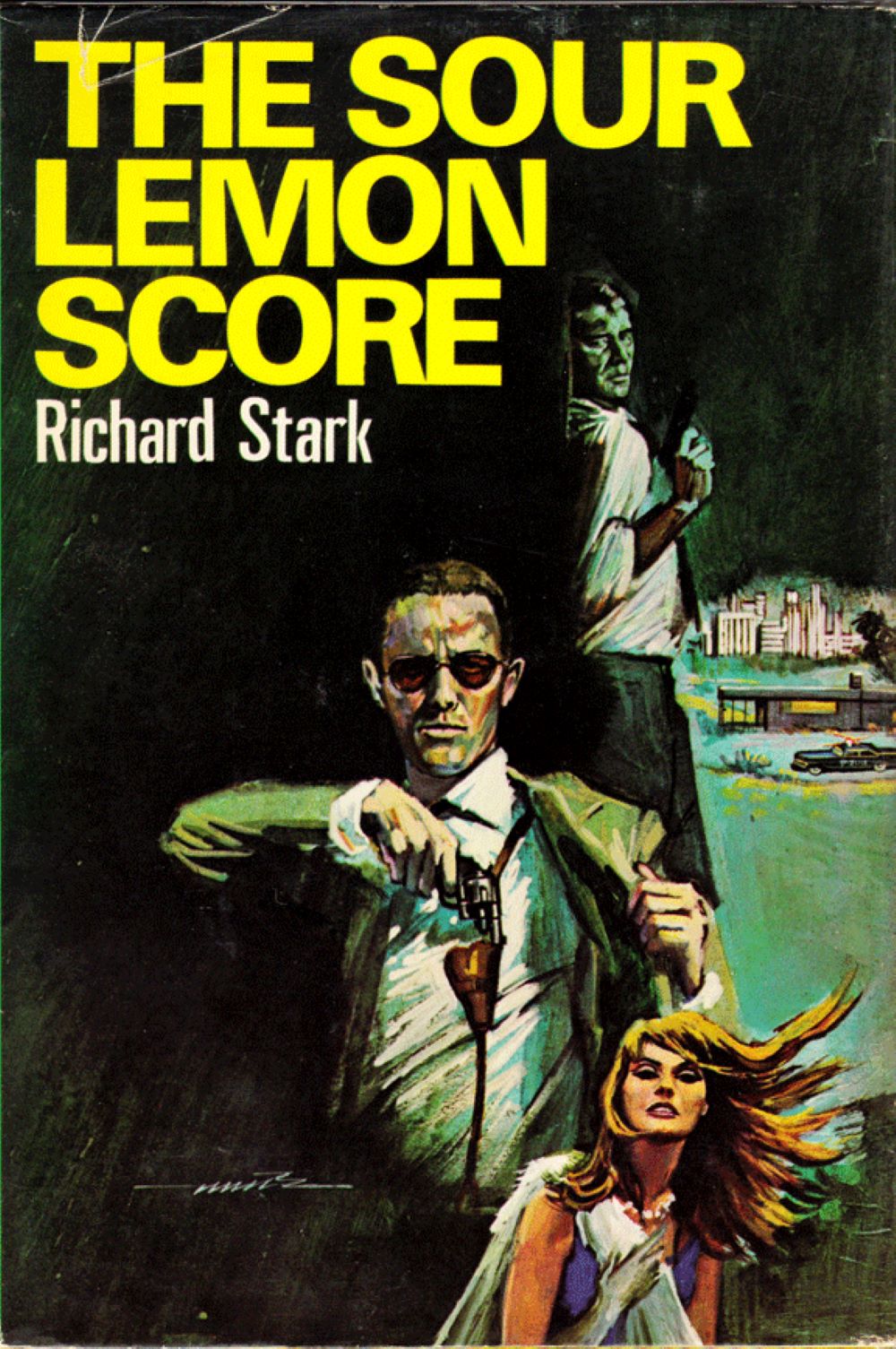

Richard Stark’s Parker novels are the kind of crime fiction that feel like they’re bad for you in all the right ways: lean, mean, amoral heist stories that work as both clinical studies of professional thieves and utterly shameless page‑turners. Taken across the 24-book run, from The Hunter in 1962 through Dirty Money in 2008, the series is remarkably consistent, yet also strange and jagged enough that you never quite relax into it. Reading Parker is like chain‑smoking noir paperbacks—self‑aware guilty pleasure with just enough bite and bleakness that you can pretend it’s good for you.

The basic premise barely changes, and that’s part of the appeal. Parker is a professional robber who prefers big, high‑yield scores: armored cars, payrolls, entire towns temporarily cut off from the world. He’s not an antihero in the modern prestige‑TV sense so much as a working stiff whose job happens to be violent crime, a man who approaches robbery with the same cold professionalism most people reserve for accounting. In The Hunter, the novel that kicks everything off, he’s double‑crossed by his wife and partner, shot, and left for dead, and the story is essentially one long act of payback as he claws his way back to New York and into the orbit of the Outfit, the crime syndicate that ultimately ends up with his money. That mix of stripped‑down revenge and procedural detail sets the tone for almost everything that follows, even when the later books drift away from personal vendetta into cleaner, job‑of‑the‑week capers.

What makes the series work—what makes it weirdly addictive—is how mercilessly Donald Westlake (under the Stark pseudonym) commits to Parker as an almost inhuman constant in a chaotic world. He’s often described by fans as a kind of force of nature, and that tracks with how he moves through these books: stoic, unadorned, perpetually assessing angles, crew members, and exit routes. Traditional redeeming qualities—sentimentality, guilt, even much curiosity about other people—just aren’t there; what you get instead is a kind of brutal efficiency that, perversely, becomes its own charisma. The guilty‑pleasure element kicks in because the novels quietly invite you to enjoy watching a ruthless pro outthink and outmuscle everyone in his path, even though the moral framework is closer to nihilism than romantic outlaw fantasy. There’s pleasure in the competence and in the clean lines of the plotting, even as you’re aware you’re rooting for someone who treats human beings like moving parts in a job.

Formally, the books have a recognizable skeleton that Stark keeps returning to and subtly bending. Most of the novels are divided into four sections: first, Parker’s point of view as he’s planning or executing a job; second, a continuation that usually ends with a betrayal or reversal; third, a shift into the perspective of whoever is double‑crossing or hunting him; and finally, a return to Parker as he fixes what’s gone wrong and settles accounts. This architecture does a couple things. It gives the series a strong procedural rhythm that fans can relax into—you know there will be a job, a screw‑up, and a payback—but it also keeps the tension high by delaying gratification until that fourth‑quarter rampage. You get both the chess match and the inevitable explosion. It’s formulaic in the same way a great blues progression is formulaic: you come for the structure, you stay for the particular variations each time.

The prose is another major part of the series’ guilty‑pleasure charge. Westlake pares the language down to something close to bare steel; the description is sparse, the sentences short, the dialogue practical and unfussy. Reviewers frequently point to how there’s “not a wasted word,” and that seems right: you feel like every line is there to move money, people, or bullets into position. In an age where a lot of thriller writing leans on verbosity and constant internal monologue, Parker’s tight focus can feel almost cleansing. At the same time, that same spareness means the violence can land with an extra jolt—there’s no cushioning around it, no moral throat‑clearing, just the fact of what Parker decides to do when someone gets in his way.

Across the series, the quality is not perfectly even, and that’s where a fair, balanced take has to admit some dips. The early stretch—The Hunter, The Man with the Getaway Face, The Outfit, The Score, and The Jugger—has a raw momentum and a sense of discovery as Westlake works out how far he can push a protagonist this cold. Later titles, especially in the first run up to Butcher’s Moon, often expand the canvas, giving more time to side characters and to elaborate, multi‑phase heists. Some readers and critics consider The Score, with its audacious robbery of an entire mining town, a high‑water mark; others see it as simply a particularly well‑executed entry in a series where the baseline is already high. Then, after the long break between the 1970s and the 1990s revival with Comeback and Backflash, you can feel Westlake adjusting the formula to a slightly different era, with Parker still fundamentally the same but the world around him updated. Those later books are often solid and occasionally excellent, but the sheer shock of the early ones is hard to recapture.

From a modern perspective, one of the more interesting tensions in reading Parker is the question of identification. The books are not satire, and they aren’t quite celebrations; they’re closer to case files written with a strong sense of style. The theme that emerges most strongly is the amoral logic of criminal enterprise: loyalty is provisional, greed is constant, and institutions—whether the Outfit or banks or small‑town cops—are just different power systems to be exploited. There’s no sentimental criminal code here, only practical rules about not talking, not freelancing, and not getting sloppy. That worldview can be bracing and, frankly, kind of fun to inhabit for a few hundred pages at a time, particularly because Westlake doesn’t ask you to endorse it; he just drops you in and lets you watch how it operates.

At the same time, that detachment and hardboiled minimalism can turn some readers off. If you need emotional growth, redemptive arcs, or a sense that the universe punishes the wicked, Parker is going to feel either empty or actively hostile to your expectations. The closest the series comes to sentiment is in Parker’s occasional, grudging respect for other professionals who do their job well—safecrackers, drivers, heist planners—and even that is strictly bounded by the demands of survival and profit. Women, in particular, can feel underwritten or instrumental in some entries, especially the earlier books, reflecting both the genre conventions of the time and the series’ focus on Parker’s narrow, self‑interested worldview. It’s possible to argue that this is part of the point—these are Parker’s stories, and he does not care about anybody’s inner life—but it does mean the books can feel airless if you’re reading a bunch in a row.

Still, that’s the strange magic of Parker: for all the limitations and repetitions, you finish one and almost immediately think about the next job, the next crew, the next betrayal. The series taps into a very specific pleasure center: watching a ruthlessly competent person navigate systems stacked with corruption and stupidity, using only planning, discipline, and a willingness to hit back harder than anyone expects. It’s not aspirational, and it’s not comforting, but it is undeniably gripping. If you can accept an unapologetically amoral center and you have a taste for stripped‑down crime fiction with a strong procedural spine, Parker is easy to devour and just as easy to feel a little guilty about enjoying as much as you do.

Previous Guilty Pleasures

- Half-Baked

- Save The Last Dance

- Every Rose Has Its Thorns

- The Jeremy Kyle Show

- Invasion USA

- The Golden Child

- Final Destination 2

- Paparazzi

- The Principal

- The Substitute

- Terror In The Family

- Pandorum

- Lambada

- Fear

- Cocktail

- Keep Off The Grass

- Girls, Girls, Girls

- Class

- Tart

- King Kong vs. Godzilla

- Hawk the Slayer

- Battle Beyond the Stars

- Meridian

- Walk of Shame

- From Justin To Kelly

- Project Greenlight

- Sex Decoy: Love Stings

- Swimfan

- On the Line

- Wolfen

- Hail Caesar!

- It’s So Cold In The D

- In the Mix

- Healed By Grace

- Valley of the Dolls

- The Legend of Billie Jean

- Death Wish

- Shipping Wars

- Ghost Whisperer

- Parking Wars

- The Dead Are After Me

- Harper’s Island

- The Resurrection of Gavin Stone

- Paranormal State

- Utopia

- Bar Rescue

- The Powers of Matthew Star

- Spiker

- Heavenly Bodies

- Maid in Manhattan

- Rage and Honor

- Saved By The Bell 3. 21 “No Hope With Dope”

- Happy Gilmore

- Solarbabies

- The Dawn of Correction

- Once You Understand

- The Voyeurs

- Robot Jox

- Teen Wolf

- The Running Man

- Double Dragon

- Backtrack

- Julie and Jack

- Karate Warrior

- Invaders From Mars

- Cloverfield

- Aerobicide

- Blood Harvest

- Shocking Dark

- Face The Truth

- Submerged

- The Canyons

- Days of Thunder

- Van Helsing

- The Night Comes for Us

- Code of Silence

- Captain Ron

- Armageddon

- Kate’s Secret

- Point Break

- The Replacements

- The Shadow

- Meteor

- Last Action Hero

- Attack of the Killer Tomatoes

- The Horror at 37,000 Feet

- The ‘Burbs

- Lifeforce

- Highschool of the Dead

- Ice Station Zebra

- No One Lives

- Brewster’s Millions

- Porky’s

- Revenge of the Nerds

- The Delta Force

- The Hidden

- Roller Boogie

- Raw Deal

- Death Merchant Series

- Ski Patrol

- The Executioner Series

- The Destroyer Series

- Private Teacher