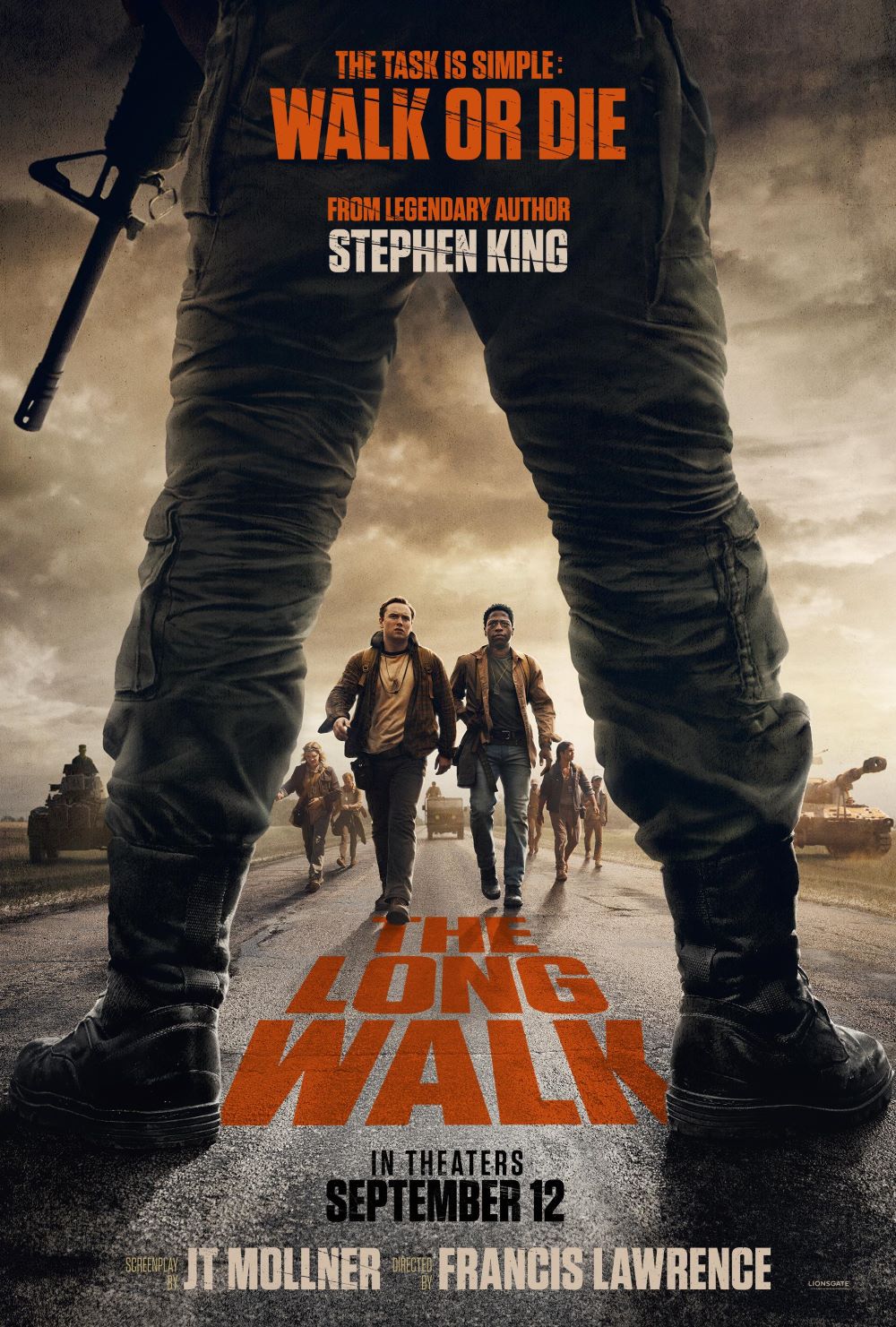

“In this Walk, it’s not about winning. It’s about refusing to be forgotten while the world watches us fade away.” — Peter McVries

Francis Lawrence’s The Long Walk (2025) delivers a relentlessly brutal and unyielding vision of dystopian horror that explores survival, authoritarian control, and the devastating loss of innocence. The film immerses viewers in a grim spectacle: fifty teenage boys forced to participate in an annual, televised event known as the Long Walk. To survive, each participant must maintain a constant pace, never falling below a minimum speed, or else face immediate execution.

At the heart of this bleak narrative is Raymond Garraty, played with earnest vulnerability by Cooper Hoffman. Garraty’s backstory, marked by the tragic execution of his father for political dissent, sets a somber tone from the outset. As the Walk drags on, Garraty forges fragile bonds with fellow contestants, particularly Peter McVries (David Jonsson), whose camaraderie and quiet resilience inject moments of hope and humanity into the harrowing journey. These relationships become the emotional core, grounding the film’s relentless physical and psychological torment in deeply human experiences.

The setting enhances this oppressive atmosphere. The time and place remain deliberately ambiguous, with evident signs that the United States has recently suffered a second Civil War. The aftermath is a landscape ruled by a harsh, authoritarian military regime overseeing a nation economically and politically in decline. Though visual cues evoke a retro, 1970s aesthetic—reflected in military hardware and daily life—the film resists pinning itself to an exact year. This timelessness amplifies its allegorical power, emphasizing ongoing societal collapse and authoritarianism without tying the story to one era specifically. The dystopian backdrop is populated by broken communities and a pervasive sense of hopelessness that mirrors the characters’ internal struggles.

Visually, The Long Walk employs stark, gritty cinematography that traps viewers in the monotonous expanse of endless roads and bleak environments. Lawrence’s direction is unflinching and unrelenting, echoing the merciless march to death and the broader commentary on institutionalized brutality. The atmospheric score complements this oppressive tone, underscoring the emotional and physical exhaustion pacing the narrative.

Performances elevate the film’s emotional stakes significantly. Hoffman’s portrayal of Garraty captures the youth’s evolving vulnerability and determination, while Jonsson’s McVries adds a poignant emotional depth with his steady, hopeful presence. Supporting actors such as Garrett Wareing’s enigmatic Billy Stebbins and Charlie Plummer’s self-destructive Barkovitch bring vital complexity and urgency. Stebbins remains a figure whose allegiance is ambiguous, adding layered mystery to the group dynamics. Judy Greer’s limited screentime as Ginny Garraty, Ray’s mother, stands out powerfully despite its brevity. Each of her appearances is heartbreaking, bringing a wrenching emotional weight to the film. Her panicked, anguished attempts to hold onto her son before he embarks on the deadly Walk amplify the human cost of the dystopian spectacle, leaving a lasting impression of maternal agony amid the surrounding brutality.

Mark Hamill’s role as The Major is a significant supporting presence, embodying the authoritarian face of the regime. The Major oversees the brutal enforcement of the Walk’s rules, commanding lethal squads who execute those who falter. Hamill brings a grim and chilling force to the character, whose cold charisma and unwavering commitment to the ruthless system make him a menacing figure. Despite relatively limited screen time compared to the young participants, The Major’s presence looms large over the story, symbolizing the chilling machinery of power and control that governs the dystopian world.

Yet, the film is stark in its depiction of violence. The executions and suffering are raw and often grotesquely explicit, serving as a damning critique of authoritarian cruelty and the voyeuristic nature of state violence televised as entertainment. This unfiltered brutality can, however, become numbing and exhausting as it piles on relentlessly, occasionally undercutting emotional resonance. The narrative embraces nihilism fully, underscoring the dehumanization and futility within the dystopian world it portrays.

The film’s overall pacing and structure reflect this bleakness but at times suffer from monotony. The heavy focus on walking and survival mechanics leads to a lack of narrative variation, testing the audience’s endurance much like the characters’. There is likewise a noticeable stretch of physical realism—the contestants endure near-impossible physical feats without adequate signs of weariness or injury, which can strain believability.

Character development is another area where the film falters slightly. While Garraty and McVries are well-drawn and immunize emotional investment, other characters tend toward archetypical roles—bullies, outsiders, or generic competitors—diminishing the impact of many deaths or interactions. Similarly, the repetitiveness of the setting and cinematography, relying mostly on basic shots following the walkers, misses opportunities for more creative visual storytelling that might heighten tension or spotlight key emotional beats.

The film’s conclusion, stark and abrupt, offers no real catharsis or closure, reinforcing the overarching theme of unyielding despair. While this resonates with the film’s nihilistic motif, it may alienate those seeking narrative resolution or hope. The visceral shock and bleak tone permeate to the end, leaving the viewer with a lasting impression of relentless suffering and sacrifice.

This demanding yet visually striking and emotionally intense film challenges viewers with its unrelenting bleakness and brutal thematic content. It critiques societal violence, media spectacle, and authoritarianism through starkly powerful performances and an oppressive, immersive atmosphere. Though it excels in evoking emotional rawness in key moments and maintaining thematic consistency, it struggles with pacing, character depth beyond the leads, and occasional narrative monotony. Its ambiguous setting in a post-second Civil War America ruled by a declining authoritarian regime adds a timeless, allegorical layer to its exploration of human endurance and societal collapse.

Ultimately, this film is best suited for viewers prepared for an uncompromising, intense vision of dystopia. It stands as a compelling, if bleak, meditation on youth, survival, and the human spirit under extreme duress, showcasing Francis Lawrence’s aptitude for crafting thought-provoking, provocative horror.