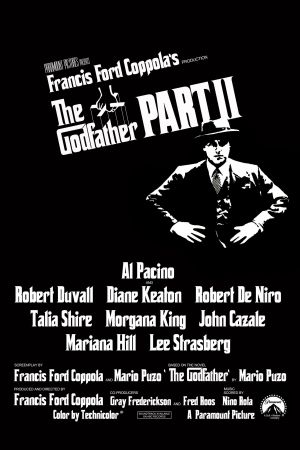

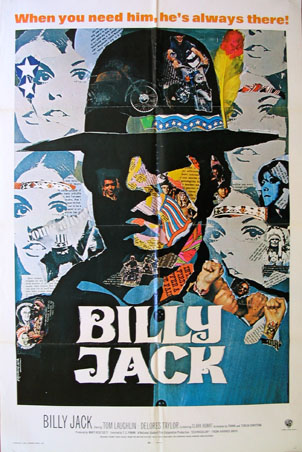

Believe it or not, The Trial of Billy Jack was not the only lengthy sequel to be released in 1974. Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Part II was released as well and it went on to become the first sequel to win an Oscar for best picture. (It was also the first, and so far, only sequel to a best picture winner to also win best picture.) Among the films that The Godfather, Part II beat: Chinatown, Coppola’s The Conversation, and The Towering Inferno. 1974 was a good year.

Whenever I think about The Godfather, Part II, I find myself wondering what the film would have been like if Richard Castellano hadn’t demanded too much money and had actually returned in the role of Clemenza, as was originally intended. In the first Godfather, Clemenza and Tessio (Abe Vigoda) were Don Corleone’s two lieutenants. Tessio was the one who betrayed Michael and was killed as a result. Meanwhile, Clemenza was the one who taught Michael how to fire a gun and who got to say, “Leave the gun. Take the cannoli.”

Though Castellano did not return to the role, Clemenza is present in The Godfather, Part II. The Godfather, Part II tells two separate stories: during one half of the film, young Vito Corleone comes to America, grows up to be Robert De Niro and then eventually becomes the Godfather. In the other half of the film, Vito’s successor, Michael (Al Pacino), tries to keep the family strong in the 1950s and ultimately either loses, alienates, or kills everyone that he loves.

During Vito’s half of the film, we learn how Vito first met Clemenza (played by Bruno Kirby) and Tessio (John Aprea). However, during Michael’s half of the story, Clemenza is nowhere to be seen. Instead, we’re told that Clemenza died off-screen and his successor is Frankie Pentangeli (Michael V. Gazzo). All of the characters talk about Frankie as if he’s an old friend but, as a matter of fact, Frankie was nowhere to be seen during the first film. Nor is he present in Vito’s flashbacks. This is because originally, Frankie was going to be Clemenza. But Richard Castellano demanded too much money and, as a result, he was written out of the script.

And really, it doesn’t matter. Gazzo does fine as Frankie and it’s a great film. But, once you know that Frankie was originally meant to be Clemenza, it’s impossible to watch The Godfather Part II without thinking about how perfectly it would have worked out.

If Clemenza had been around for Michael’s scenes, he would have provided a direct link between Vito’s story and Michael’s story. When Clemenza (as opposed to Frankie) betrayed Michael and went into protective custody, it would have reminded us of how much things had changed for the Corleones (and, by extension, America itself). When Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall) talked Clemenza (as opposed to Frankie) into committing suicide, it truly would have shown that the old, “honorable” Mafia no longer existed. It’s also interesting to note that, before Tessio was taken away and killed, the last person he talked to was Tom Hagen. If Castellano had returned, it once again would have fallen to Tom to let another one of his adopted father’s friends know that it was time to go.

Famously, the Godfather, Part II ends with a flashback to the day after Pearl Harbor. We watch as a young and idealistic Michael tells his family that he’s joined the army. With the exception of Michael and Tom Hagen, every character seen in the flashback has been killed over the course of the previous two films. We see Sonny (James Caan), Carlo (Gianni Russo), Fredo (John Cazale), and even Tessio (Abe Vigoda). Not present: Clemenza. (Vito doesn’t appear in the flashback either but everyone’s talking about him so he might as well be there. Poor Clemenza doesn’t even get mentioned.)

If only Richard Castellano had been willing to return.

But he didn’t and you know what? You really only miss him if you know that he was originally meant to be in the film. With or without Richard Castellano, The Godfather, Part II is a great film, probably one of the greatest of all time. When it comes to reviewing The Godfather, Part II, the only real question is whether it’s better than the first Godfather.

Which Godfather you prefer really depends on what you’re looking for from a movie. Even with that door getting closed in Kay’s face, the first Godfather was and is a crowd pleaser. In the first Godfather, the Corleones may have been bad but everyone else was worse. You couldn’t help but cheer them on.

The Godfather Part II is far different. In the “modern” scenes, we discover that the playful and idealistic Michael of part one is gone. Micheal is now cold and ruthless, a man who willingly orders a hit on his older brother and who has no trouble threatening Tom Hagen. If Michael spent the first film surrounded by family, he spends the second film talking to professional killers, like Al Neri (Richard Bright) and Rocco Lampone (Tom Rosqui). Whereas the first film ended with someone else closing the door on Kay, the second film features Michael doing it himself. By the end of the film, Michael Corleone is alone in his compound, a tyrant isolated in his castle.

Michael’s story provides a sharp contrast to Vito’s story. Vito’s half of the film is vibrant and colorful and fun in a way that Michael’s half is not and could never be. But every time that you’re tempted to cheer a bit too easily for Vito, the film moves forward in time and it reminds you of what the future holds for the Corleones.

So, which of the first two Godfathers do I prefer? I love them both. If I need to be entertained, I’ll watch The Godfather. If I want to watch a movie that will truly make me think and make me question all of my beliefs about morality, I’ll watch Part Two.

Finally, I can’t end this review without talking about G.D. Spradlin, the actor who plays the role of U.S. Sen. Pat Geary. The Godfather Part II is full of great acting. De Niro won an Oscar. Pacino, Gazzo, Lee Strasberg, and Talia Shire were all nominated. Diane Keaton, Robert Duvall, and John Cazale all deserved nominations. Even Joe Spinell shows up and brilliantly delivers the line, “Yeah, we had lots of buffers.” But, with each viewing of Godfather, Part II, I find myself more and more impressed with G.D. Spradlin.

Sen. Pat Geary doesn’t have a lot of time on-screen. He attends a birthday party at the Corleone Family compound, where he praises Michael in public and then condescendingly insults him in private. Later, he shows up in Cuba, where he watches a sex show with obvious interest. And, when Michael is called before a Senate committee, Geary gives a speech defending the honor of all Italian-Americans.

But the scene that we all remember is the one where Tom Hagen meets Sen. Geary in a brothel. As Geary talks about how he passed out earlier, the camera briefly catches the sight of a dead prostitute lying on the bed behind him. What’s especially disturbing about this scene is that neither Hagen nor Geary seem to acknowledge her presence. She’s been reduced to a prop in the Corleone Family’s scheme to blackmail Sen. Geary. His voice shaken, Geary says that he doesn’t know what happened and we see the weakness and the cowardice behind his almost all-American facade.

It’s a disturbing scene that’s well-acted by both Duvall and Spradlin. Of course, what is obvious (even if it’s never explicitly stated) is that Sen. Geary has been set up and that nameless prostitute was killed by the Corleones. It’s a scene that makes us reconsider everything that we previously believed about the heroes of the Godfather.

For forcing us to reconsider and shaking us out of our complacency, The Godfather, Part II is a great film.

(Yes, it’s even better than The Trial of Billy Jack.)