“Do they have the car?”

“We have the driver.”

Those two lines of dialogue, uttered towards the end of the film, pretty much sums up F1, a terrifically entertaining movie about Formula One racing.

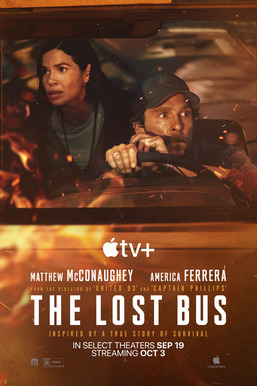

Brad Pitt stars as Sonny Hayes, a former FI prodigy who, in the early 90s, suffered a traumatic crash at the Spanish Grand Prix. The crash nearly killed him and it temporarily ended his career as an F1 driver. Sonny has spent the past thirty years as a drifter, gambler, and as a race car driver for hire. He lives in a van and is haunted by nightmares of his crash. When he wakes up in the morning, he groans as he stretches his tattooed, beat-up, but still muscular body. He dunks his face in a sink full of ice. He’s aging but he hasn’t surrendered just yet. The film opens with Sonny helping to win the 24 Hours of Daytona race. After his victory, he’s approached by his former teammate, Ruben (Javier Bardem). Ruben is in charge of the APEXGP F1 team. He needs a driver to partner with the young and arrogant Joshua Pearce (Damson Idris). Sonny agrees, though only after Ruben asks if Sonny wants a chance to show that he’s the best in the world. Sonny may be one of the oldest guys on the track but he’s still got something to prove.

If F1 came out in 80s, the 90s, or even the Aughts, it would be viewed as a well-made but predictable racing film, one in which a fairly by-the-numbers script was held together by Brad Pitt’s overwhelming charisma and Joseph Kosiniski’s kinetic direction. And that certainly is a legitimate way to view the film in 2025. On the other hand, coming after both the scoldy Woke Era and the authoritarian COVID Era, a film that celebrates competing without guilt, that says that it’s more fun to win than to lose, and which doesn’t apologize for embracing a culture of driving fast and breaking the rules feels almost revolutionary. Just as he did with Top Gun: Maverick, director Joseph Kosinski reminds the audience that it’s okay to be entertained. Not everything has to be a struggle session. Not everything has to be a rejection of the things that once made you happy. F1 is a film that invites you to cheer without guilt or shame.

It’s a good film, one that is full of exciting racing scenes and gasp-inducing crashes. After both this film and Top Gun: Maverick, there’s little doubt that director Joseph Kosinski knows how to harness the power of Hollywood’s few true movie stars. That said, as good as Brad Pitt is, Damson Idris is equally impressive, playing Joshua, a young driver who learns that there’s more to being a great driver than just getting good press. When we first meet Joshua, he’s young and cocky and arrogant and one thing that I respect about the film is that, even after Joshua learns the importance of teamwork and trust, he’s still more than a little cocky. He never stops believing in himself. He doesn’t sacrifice his confidence on the way to becoming the best. Though the film is definitely on Sonny’s side when it comes to their early conflicts (one can practically here the film saying, “Put down your phone, you young whippersnapper!”), it’s smart enough to not make Joshua into a caricature. Instead, he’s just a young man trying to balance celebrity and talent. Kerry Condon also gives a good performance as APEX’s technical director, though her romance with Sonny does feel a bit tacked on. (Far too often, whenever a female character says that she’s not looking for a relationship, movies refuse to take her word for it.)

When I first heard about F1, I have to admit that I wondered if Kosinski was deliberately following up the Top Gun sequel with a remake of Days of Thunder.It is true that F1 does have a lot in common with other racing films but, in the end, it doesn’t matter. Brad Pitt’s star turn and Joseph Kosinski’s direction makes F1 into an absolutely thrill ride and one of the best of 2025.