4 Or More Shots From 4 Or More Films is just what it says it is, 4 shots from 4 of our favorite films. As opposed to the reviews and recaps that we usually post, 4 Shots From 4 Films lets the visuals do the talking!

4 Shots From 4 Heavenly Films

4 Or More Shots From 4 Or More Films is just what it says it is, 4 shots from 4 of our favorite films. As opposed to the reviews and recaps that we usually post, 4 Shots From 4 Films lets the visuals do the talking!

4 Shots From 4 Heavenly Films

In Alan J. Pakula’s 1974 film The Parallax View, Warren Beatty plays a seedy journalist who goes undercover to investigate the links between the mysterious Parallax Corporation and a series of recent political assassinations. In the film’s most famous sequence, Beatty — pretending to be a job applicant (read: potential assassin) for the Parallax Corporation — is shown an orientation film that has been designed to test whether or not he’s a suitable applicant. The montage is shown in its entirety, without once cutting away to show us Beatty’s reaction. The implication, of course, is that what’s important isn’t how Beatty reacts to the montage but how the viewers sitting out in the audience react.

So, at the risk of furthering the conspiracy, here’s that montage.

Filmed in 1957 for a television program called Westinghouse Studio One, The Night America Trembled is a dramatization of the night that Orson Welles terrified America with his radio adaptation of War of The Worlds.

For legal reasons, Orson Welles is not portrayed nor is his name mentioned. Instead, the focus is mostly on the people listening to the broadcast and getting the wrong idea. That may sound like a comedy but The Night America Trembled takes itself fairly seriously. Even pompous old Edward R. Murrow shows up to narrate the film, in between taking drags off a cigarette.

Clocking in at a brisk 60 minutes, The Night America Trembled is an interesting recreation of that October 30th. Among the people panicking: a group of people in a bar who, before hearing the broadcast, were debating whether or not Hitler was as crazy as people said he was, a babysitter who goes absolutely crazy with fear, and a group of poker-playing college students. If, like me, you’re a frequent viewer of TCM, you may recognize some of the faces in the large cast: Ed Asner, James Coburn, John Astin, Warren Oates, and Warren Beatty all make early appearances.

It’s an interesting little historical document and you can watch it below!

In this scene, from Arthur Penn’s 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie Parker (played by Faye Dunaway) writes a poem and tries to craft the future image of Bonnie and Clyde. Though it has none of the violence that made Bonnie and Clyde such a controversial film in 1967, this is still an important scene. (Actually, it’s more than one scene.) Indeed, this scene is a turning point for the entire film, the moment that Bonnie and Clyde goes from being an occasionally comedic attack on the establishment to a fatalistic crime noir. This is where Bonnie shows that, unlike Clyde, she knows that death is inescapable but she also knows that she and Clyde are destined to be legends.

(Of course, Dunaway and Warren Beatty — two performers who once epitomized an era but who are only seen occasionally nowadays — are already legends.)

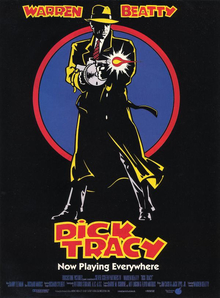

The year is 1937 and “Big Boy” Caprice (Al Pacino) and his gang of flamboyant and often disfigured criminals are trying to take over the rackets. Standing in their way is ace detective Dick Tracy (Warren Beatty), the yellow trench-wearing defender of the law. Tracy is not only looking to take down Caprice but he and Tess Trueheart (Glenne Headly) are currently the guardians of The Kid (Charlie Korsmo), a young street kid who witnessed one of Caprice’s worst crimes. Tracy’s investigation leads him through a rogue’s gallery of criminals and also involves Breathless Mahoney (Madonna), who has witnessed many of Caprice’s crimes but who also wants to steal Tracy’s heart from Tess.

The year is 1937 and “Big Boy” Caprice (Al Pacino) and his gang of flamboyant and often disfigured criminals are trying to take over the rackets. Standing in their way is ace detective Dick Tracy (Warren Beatty), the yellow trench-wearing defender of the law. Tracy is not only looking to take down Caprice but he and Tess Trueheart (Glenne Headly) are currently the guardians of The Kid (Charlie Korsmo), a young street kid who witnessed one of Caprice’s worst crimes. Tracy’s investigation leads him through a rogue’s gallery of criminals and also involves Breathless Mahoney (Madonna), who has witnessed many of Caprice’s crimes but who also wants to steal Tracy’s heart from Tess.

Based on the long-running comic strip, Dick Tracy was a labor of love on the part of Warren Beatty. Not only starring but also directing, Tracy made a film that stayed true to the look and the feel of the original comic strip (the film’s visual palette was limited to just seven colors) while also including an all-star cast the featured Madonna is an attempt to appeal to a younger audience who had probably never even heard of Dick Tracy. When Dick Tracy was released, the majority of the publicity centered around Madonna’s participation in the film and the fact that she was dating Beatty at the time. Madonna is actually probably the weakest element of the film. More of a personality than an actress, Madonna is always Madonna no matter who she is playing and, in a film full of famous actors managing to be convincing as the members of Dick Tracy’s rogue gallery, Madonna feels out of place. Michelle Pfeiffer would have been the ideal Breathless Mahoney.

It doesn’t matter, though, because the rest of the film is great. It’s one of the few comic book films of the 90s to really hold up, mostly due to Beatty’s obvious enthusiasm for the material and the performances of everyone in the supporting cast who was not named Madonna. Al Pacino received an Oscar nomination for playing Big Boy Caprice but equally good are Dustin Hoffman as Mumbles, William Forsythe as Flaptop, R.G. Armstong as Pruneface, and Henry Silva as Influence. These actors all create memorable characters, even while acting under a ton of very convincing makeup. I also liked Dick Van Dyke as the corrupt District Attorney. Beatty knew audience would be shocked to see Van Dyke not playing a hero and both he and Van Dyke play it up for all its worth. Beatty embraces the comic strip’s campiness while still remaining respectful to its style and the combination of Danny Elfman’s music and Stephen Sondheim’s songs provide just the right score for Dick Tracy’s adventures. The film can be surprisingly violent at times but the same was often said about the Dick Tracy comic strip. It wasn’t two-way wrist radios and trips to the Moon. Dick Tracy also dealt with the most ruthless and bloodthirsty gangsters his city had to offer.

Dick Tracy was considered to be a box office disappointment when it was originally released. (Again, you have to wonder if Beatty overestimated how many fans Dick Tracy had in 1990.) But it holds up well and is still more entertaining than several of the more recent comic book movies that have been released.

Today, we wish a happy birthday to actor, director, and producer Warren Beatty!

This wonderfully-acted scene that I love comes from Beatty’s 1978 film, Heaven Can Wait. In this scene Warren Beatty plays a character who attempts to convince his friend (Jack Warden) that he has come back from the dead and is inhabiting the body of an old millionaire. (Watch the film, it makes sense.) James Mason plays the erudite angel that only Beatty can see.

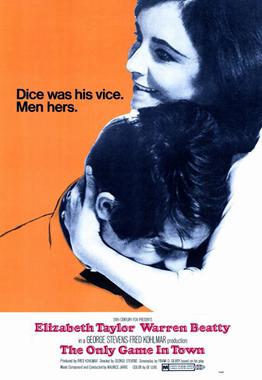

Fran Walker (Elizabeth Taylor) is an aging Vegas showgirl who has been abandoned by her married lover (Charles Braswell). A trip to a piano bar leads to her meeting pianist and gambling addict Joe Grady (Warren Beatty). Frank brings Joe home with her. Joe is trying to win $5,000 so he can leave Las Vegas and go to New York. Fran needs someone to keep her from going to back to her go-nowhere relationship. The two talk and talk. And talk.

Fran Walker (Elizabeth Taylor) is an aging Vegas showgirl who has been abandoned by her married lover (Charles Braswell). A trip to a piano bar leads to her meeting pianist and gambling addict Joe Grady (Warren Beatty). Frank brings Joe home with her. Joe is trying to win $5,000 so he can leave Las Vegas and go to New York. Fran needs someone to keep her from going to back to her go-nowhere relationship. The two talk and talk. And talk.

Based on a play that closed after 16 performances, The Only Game In Town is memorable for being one of the most expensive theatrical adaptations ever produced. That’s because Taylor insisted on filming in Paris instead of Las Vegas. A set representing Fran’s tiny apartment (which is supposed to look cheap) was built on a Paris soundstage and the budget ballooned to a then unheard of $11,000,000. (By today’s standards, that would be a $90,461,391 budget for a film with two stars and only a handful of locations.) The Only Game In Town is also memorable for being the only film to feature both Elizabeth Taylor and Warren Beatty. Taylor and Beatty were actually close in age but Fran still seems to be several decades older than Joe. It was not the script’s intention but, due to the age difference, Joe comes across as being a gigolo. (Originally, Frank Sinatra was cast as Joe but he left while the sets were being made in France.) Finally, this was the final film to be directed by George Stevens, one of the great Golden Age directors who found himself struggling to keep up in a changing Hollywood. With its stagey set-up and it’s dialogue-heavy script, this film does not features Stevens’s best work.

The Only Game In Town was a huge flop when released, damaging Taylor’s already floundering career and making Beatty even more determined to eventually direct his own films. Seen today, Warren Beatty is actually pretty good in his role, even if he does come across as being too young. Elizabeth Taylor is not served well by any element of the film, from her matronly (but expensive) costumes or a script the encourages her to be shrill. The Only Game In Town was not one that anyone won.

First released in 1971, McCabe & Mrs. Miller takes place in the town of Presbyterian Church at the turn of the 19th Century.

Presbyterian Church is a mining town in Washington State. When we first see the town, there’s not much to it. The town is actually named after its only substantial building and the residents refer to the various parts of the town as either being on the right side or the left side of the church. The rest of the town is half-constructed and appears to be covered in a permanent layer of grime. This is perhaps the least romantic town to ever appear in a western and it is populated largely by lazy and bored men who pass the time gambling and waiting for something better to come along.

When a gambler who says that he is named McCabe (Warren Beatty) rides into town, it causes a flurry of excitement. The man is well-dressed and well-spoken and it’s assumed that he must be someone important. Soon a rumor spreads that McCabe is an infamous gunfighter named Pudgy McCabe. Pudgy McCabe is famous for having used a derringer to shoot a man named Atwater. No one is really sure who Atwater was or why he was shot but everyone agrees that it was impressive.

McCabe proves himself to be an entrepreneur. He settles down in Presbyterian Church and establishes himself as the town’s pimp. Soon, he is joined by a cockney madam names Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie). The two of them go into business together and soon, Presbyterian Church has its own very popular bordello. Sex sells and Presbyterian Church becomes a boomtown. It attracts enough attention that two agents of a robber baron approach McCabe and offer to buy him out. McCabe refuses, thinking that he’ll get more money if he holds out. Mrs. Miller informs him that the men that he’s dealing with don’t offer to pay more money. Instead, they just kill anyone who refuses their initial offer.

Three gunmen do eventually show up at Presbyterian Church and we do eventually get an answer to the question of whether or not McCabe killed Atwater or if he’s just someone who has borrowed someone else’s legend. The final gunfight occurs as snow falls on the town and the townspeople desperately try to put out a fire at the church. No one really notices the fact that McCabe is fighting for his life at the time and, as befits a revisionist western, there’s nothing romantic or dignified about the film’s violence. McCabe is not above shooting a man in the back. The killers are not above tricking an innocent cowboy (poor Keith Carradine) into reaching for his gun so that they’ll have an excuse so gun him down. McCabe may be responsible for making Presbyterian Church into a boomtown but no one is willing to come to his aid. The lawyer (William Devane) that McCabe approaches is more interested in promoting his political career than actually getting personally involved in the situation. Mrs. Miller, a businesswoman first, smokes in an opium den with an air of detachment while the snow falls outside.

It’s a dark story with moments of sardonic humor. It’s also one of director Robert Altman’s best. The story of McCabe and Mrs. Miller and the three gunmen is far less important than the film’s portrayal of community growing and changing. Featuring an ensemble cast and Altman’s trademark overlapping dialogue, McCabe & Mrs. Miller puts the viewer right in the heart of Presbyterian Church. There are usually several stories playing out at once and it’s often up to the viewer to decide which one that they want to follow. Yes, the film is about Warren Beatty’s slick but somewhat befuddled McCabe and Julie Christie’s cynical Mrs. Miller. But it’s just as much about Keith Carradine’s Cowboy and Rene Auberjonois’s innkeeper. Corey Fischer, Michael Murphy, John Schuck, Shelley Duvall, Bert Remsen, and a host of other Altman mainstays all have roles as the people who briefly come into the orbit of either McCabe or Mrs. Miller. Every character has a life and a story of their own. McCabe & Mrs. Miller is a film that feels as if it is truly alive.

As with many of Altman’s films, McCabe & Mrs. Miller was not fully appreciated when initially released. The intentionally muddy look and the overlapping dialogue left some critics confused and the film’s status as a western that refused to play by the rules of the genre presented a challenge to audience members who may have just wanted to see Warren Beatty fall in love with Julie Christie and save the town. But the film has endured and is now recognized as one of the best of the 70s.

In the 1981 film Reds, Warren Beatty plays Jack Reed, the radical journalist who, at the turn of the century, wrote one of the first non-fiction books about Russia’s communist revolution and then went on to work as a propagandist for the communists before becoming disillusioned with the new Russian government and then promptly dying at the age of 32.

Diane Keaton plays Louise Bryant, the feminist writer who became Reed’s lover and eventually his wife. Louise found fame as one of the first female war correspondents but then she also found infamy when she was called before a Congressional committee and accused of being a subversive.

Jack Nicholson plays Eugene O’Neill, the playwright who was a friend of both Reed and Bryant’s and who had a brief affair with Bryant while Reed was off covering labor strikes and the 1916 Democratic Convention.

Lastly, Maureen Stapleton plays Emma Goldman, the anarchist leader who was kicked out of the country after one of her stupid little dumbass followers assassinated President McKinley. (Seriously, don’t get me started on that little jerk Leon Czolgosz.)

Together …. well, I was going to say that they solve crimes but that joke is perhaps a bit too flippant for a review of Reds. Reds is a big serious film about the left-wing activists at the turn of the century, one in which the characters move from one labor riot to another and generally live the life of wealthy bohemians. Reed spends the film promoting communism, just to be terribly disillusioned when the communists actually come to power in Russia. For a history nerd like me, the film is interesting. For those who are not quite as obsessed with history, the film is extremely long and the scenes of Reed and Bryant’s domestic dramas often feel a bit predictable, especially when they’re taking place against such a large international tableaux. At its best, the film is almost a Rorschach test for how the viewer feels about political and labor activists. Do you look at Jack Reed and Louise Bryant and see two inspiring warriors for the cause or do you see two wealthy people playing at being revolutionaries?

Reds was a film that Warren Beatty spent close to 20 years trying to make, despite the fact that the heads of the Hollywood studios all told him that audiences would never show up for an epic film about a bunch of wealthy communists. (The heads of the studio turned out to be correct, as the film was critically acclaimed but hardly a success at the box office.) It was only after the success of the 1978, Beatty-directed best picture nominee Heaven Can Wait that Beatty was finally able to get financing for his dream project. He ended up directing, producing, and writing the film himself and he cast his friend Jack Nicholson as O’Neill and his then-romantic partner Diane Keaton as Louise Bryant. (Gene Hackman, Beatty’s Bonnie and Clyde co-star, shows up briefly as one of Reed’s editors.) One left-wing generation’s tribute to an early left-wing generation, Reds is fully a Warren Beatty production and, for his efforts, Beatty was honored with the Oscar for Best Director. That said, the Reds lost the award for Best Picture to another historical epic, Chariots of Fire. Chariots of Fire featured no communists and did quite well at the box office.

The film is good but a bit uneven, especially towards the end when we suddenly get scenes of Louise Bryant trudging through Finland as she attempts to make it to Russia to be reunited with Reed. The film actually works best when it features interviews with people who were actual contemporaries of Reed and Bryant and who share their own memoires of the time. In fact, the interviews work almost too well. The “witnesses,” as the film refers to them, paint such a vivid picture of the Reed, Bryant, and turn of the century America that Beatty’s attempt to cinematically recreate history often can’t compete. One can’t help but feel that Beatty perhaps should have just made a documentary instead of a narrative film.

(Interestingly enough, many of the witnesses were people who were sympathetic to Reed’s politics in at the start of the century but then moved much more to the right as the years passed. Reed’s friend and college roommate, Hamilton Fish, went on to become a prominent Republican congressman and a prominent critics of FDR.)

That said, Jack Nicholson gives a fantastic performance as Eugene O’Neill, adding some much needed cynicism to the film’s portrayal of Reed and Bryant’s idealism. Keaton and Beatty sometime both seem to be struggling to escape their own well-worn personas as Bryant and Reed but Beatty does really sell Reed’s eventually disillusionment with Russia and the scene where he finally tells off his Russian handler made me want to cheer. Fans of great character acting will want to keep an eye out for everyone from Paul Sorvino to William Daniels to Edward Herrmann to M. Emmet Walsh and IanWolfe, all popping up in small roles.

Reds is not a perfect film but, as a lover of history, I enjoyed it.

Filmed in 1957 for a television program called Westinghouse Studio One, The Night America Trembled is a dramatization of the night that Orson Welles terrified America with his radio adaptation of War of The Worlds.

For legal reasons, Orson Welles is not portrayed nor is his name mentioned. Instead, the focus is mostly on the people listening to the broadcast and getting the wrong idea. That may sound like a comedy but The Night America Trembled takes itself fairly seriously. Even pompous old Edward R. Murrow shows up to narrate the film, in between taking drags off a cigarette.

Clocking in at a brisk 60 minutes, The Night America Trembled is an interesting recreation of that October 30th. Among the people panicking: a group of people in a bar who, before hearing the broadcast, were debating whether or not Hitler was as crazy as people said he was, a babysitter who goes absolutely crazy with fear, and a group of poker-playing college students. If, like me, you’re a frequent viewer of TCM, you may recognize some of the faces in the large cast: Ed Asner, James Coburn, John Astin, Warren Oates, and Warren Beatty all make early appearances.

It’s an interesting little historical document and you can watch it below!