“This thing… called a heart… it’s just a dream.” — Guts

The 1997 Berserk anime adaptation dives headfirst into Kentaro Miura’s brutal manga world, turning its already savage Golden Age arc into a gut-wrenching visual nightmare that still haunts fans nearly three decades later. This 25-episode series, aired from October 1997 to March 1998, kicks off with a flash-forward to Guts as the Black Swordsman before rewinding to his mercenary days with Griffith’s Band of the Hawk, capturing the raw rise-and-fall tragedy without pulling punches. What makes it stand out is how it cranks up the manga’s inherent darkness, using stark animation and eerie sound design to make themes of betrayal, rape, and demonic sacrifice feel even more inescapable and visceral.

Right from the opener, Berserk the anime slams you with a blood-soaked tease of Guts’ rage-fueled future, setting a tone that’s less hopeful fantasy and more unrelenting descent into hell. The manga already paints a medieval-inspired world of endless war, ambition, and causality—where fate pulls strings like puppet masters—but the anime condenses this into a tighter, more oppressive narrative arc. It skips some manga side elements like Puck the elf or deeper political intrigue in Midland, which actually sharpens the focus on human frailty, making the horror hit harder without distractions. Critics have called it the pinnacle of dark fantasy, praising how its hand-drawn grit and shadowy palettes evoke the ugliness of war better than polished modern takes.

At its core, the series explores ambition’s toxic price through Griffith, the silver-haired charmer whose dream of kingship devours everyone around him. In the manga, Griffith’s charisma shines amid detailed backstories, but the anime amplifies his fall by lingering on his psychological cracks—torture scenes drag with feverish close-ups, his tongue severed, body broken, eyes hollowed out in a way that feels more pathetic and monstrous than the page’s subtlety. This ramps up the grimness; where Miura’s art might imply despair through intricate shading, the anime’s limited budget forces raw, unflinching stares that bore into your soul, turning Griffith from lowborn visionary into a symbol of corrupted free will. Guts, voiced with gravelly intensity by Nobutoshi Canna, embodies endless struggle—born from a corpse, abused as a kid (hinted brutally but not shown in full like the manga), he swings his massive Dragonslayer like an extension of his trauma.

Casca’s arc gets the darkest upgrade, transforming her from fierce Hawk commander to shattered victim in ways that make the manga’s tragedy feel almost restrained. The anime doesn’t shy from her rape during the Eclipse—depicted with nightmarish silence, blood sprays, and Femto’s (Griffith reborn) cold violation right before Guts’ helpless eyes—losing his arm and eye in a frenzy of futile rage. Manga fans note how the adaptation’s Eclipse outdoes even later films in horror: black voids swallow screams, demons tear flesh with grotesque intimacy, and the lack of music lets raw voice acting convey utter hopelessness. This isn’t gratuitous; it’s the manga’s themes of human nature’s depths—betrayal, causality’s spiral, religion as blind comfort—boiled down to soul-crushing visuals that linger longer than words on a page. The God Hand’s emergence, offering Griffith godhood for his band’s sacrifice, hits like cosmic indifference, making the Eclipse not just gore but a philosophical gut-punch on destiny versus defiance.

Susumu Hirasawa’s soundtrack seals the deal, with synth-heavy tracks like “Forces” and “Guts” weaving ethereal dread into every sword clash and quiet betrayal. Where the manga relies on Miura’s hyper-detailed panels for atmosphere, the anime’s OST—haunting flutes over clanging armor—amplifies isolation, turning battles into dirges and the Eclipse into a silent scream. It’s no wonder fans say time flies despite the deliberate pacing; the slow build to horror keeps you hooked, pondering ambition’s cost and humanity’s fragility.

Culturally, the 1997 Berserk anime exploded as a gateway drug to dark fantasy, pulling in viewers who then devoured the manga and reshaped anime tastes. Before it, Japanese fantasy leaned lighter—think Dragon Quest quests—but Berserk proved you could blend Conan the Barbarian savagery with psychological depth, influencing giants like Attack on Titan‘s doomed soldiers, Goblin Slayer‘s trauma-soaked gore, and even Game of Thrones-style betrayals. It sold millions, won Tezuka Osamu nods for the manga, and got rereleased on Blu-ray as recently as 2024, proving its timeless pull. Western critics hail it as intellectually demanding, transcending tropes with Kurosawa-like violence that underscores humanity amid apocalypse.

The anime dials up the manga’s grimness by necessity—budget constraints meant fewer frills, so every frame prioritizes emotional weight over flash, making demons feel mythically terrifying and losses irreparable. Manga’s Golden Age builds subtle bonds; the show condenses them into feverish intensity, so Griffith’s sacrifice stings deeper, Guts’ rage boils hotter. Themes like predetermination—Guts branded for endless demon pursuit—gain visual permanence via the glowing Brand of Sacrifice, a constant night-haunting reminder absent in static panels. Religion’s critique shines too: Midland’s church ignores atrocities until apostles devour believers, a bleak commentary amplified by animation’s hordes of mangled corpses.

Even flaws enhance the darkness—no fairy-tale elf Puck lightens moods, politics skimmed leave a hollow kingdom, and the cliffhanger ending (mid-Eclipse tease) mirrors life’s unfinished cruelties. Later adaptations like 2016’s CGI mess diluted this; 1997’s raw style keeps the manga’s mud-and-blood realism intact, arguably grimmer for its restraint. Voice acting sells it—Canna’s guttural roars, Yuko Miyamura’s Casca cracking under pressure—pairing with Hirasawa’s score to etch trauma into memory.

Today, Berserk‘s legacy towers: over 70 million manga copies sold, crossovers in Diablo IV, endless merch, and debates on its Eclipse as anime’s bleakest peak. It proved dark themes—child abuse hints, schizophrenia-like breaks, ambition’s cannibalism—could captivate without cheap shocks, birthing “grimdark” as genre staple. For a low-budget ’97 relic, it outshines flashier takes by leaning into despair, making Miura’s world feel like fate’s cruel joke you can’t look away from.

Diving deeper into why it darkens the source: manga’s art allows interpretive distance—shadowed horrors imply pain—but anime forces confrontation, blood arcing in real-time, faces twisting in agony. Guts’ childhood rape allusion becomes a spectral flashback nightmare; Griffith’s torture a year-long montage of pus and screams, eroding his beauty into ruin. The Hawks’ slaughter isn’t panel-flipped pages but prolonged screams fading to silence, each apostle maw chewing comrades we grew to love—Judeau’s wit silenced, Pippin’s bulk rent apart. This visceral amp makes causality’s theme suffocating: no escape, just branded survival in a demon-riddled world.

Culturally, it bridged East-West fantasy gaps, echoing Hellraiser body horror and Excalibur medieval grit while predating Dark Souls (born from Miura’s influence). Fans worldwide cite it as therapy-triggering yet cathartic, sparking forums on trauma, resilience, toxic bonds. Its impact endures—Miura’s 2021 passing spiked sales, proving Berserk as monolith.

Ultimately, the 1997 adaptation doesn’t just adapt; it weaponizes the manga’s shadows, forging a bleaker legend that demands you question humanity’s fight against oblivion.

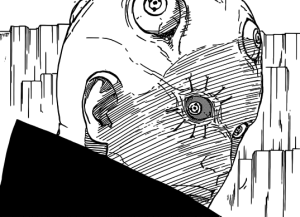

Stand Alone Complex lies much closer to the root of my music series, because some of the key issues it tackles have since arisen online in the real world. Everyone is well familiar with the use of V for Vendetta-styled Guy Fawkes masks in protests originating from the internet, but there is a decent chance you have also caught a glimpse of an odd blue smiley face among the rabble. The Laughing Man image originates from Stand Alone Complex, where it functions as a mask employed anonymously by individuals taking public action independently of each other. At first, an advocate for social justice uses it to disguise himself while committing a ‘terrorist’ act, but the image quickly overreaches his motives. Others commit unrelated political sabotage under the guise. Corporations employ it to discredit their competitors. Pranksters use it as a sort of meme, forming the shape with chairs on a rooftop and cutting it into a field as a crop circle, for instance. The image has no concrete meaning, and everyone who uses it essentially ‘stands alone’, but the public perceive the Laughing Man as a single individual.

Stand Alone Complex lies much closer to the root of my music series, because some of the key issues it tackles have since arisen online in the real world. Everyone is well familiar with the use of V for Vendetta-styled Guy Fawkes masks in protests originating from the internet, but there is a decent chance you have also caught a glimpse of an odd blue smiley face among the rabble. The Laughing Man image originates from Stand Alone Complex, where it functions as a mask employed anonymously by individuals taking public action independently of each other. At first, an advocate for social justice uses it to disguise himself while committing a ‘terrorist’ act, but the image quickly overreaches his motives. Others commit unrelated political sabotage under the guise. Corporations employ it to discredit their competitors. Pranksters use it as a sort of meme, forming the shape with chairs on a rooftop and cutting it into a field as a crop circle, for instance. The image has no concrete meaning, and everyone who uses it essentially ‘stands alone’, but the public perceive the Laughing Man as a single individual. Ghost in the Shell has remained a uniquely relevant franchise in science fiction because it got so many ideas right. In 1989, at a time when internet was still a novelty of college libraries, the manga offered a world of total connectivity, where every human and device belonged to a global network. In 2002, Stand Alone Complex introduced the Laughing Man, and shortly afterwards the real world knew an equivalent. Whether this bodes well for the franchise’s dabblings into cyborg technology, only time can tell, but history has certainly made an inherently fascinating fictional world all the more compelling. In the Ghost in the Shell universe, science has fully bridged the gap between computers and neural systems, allowing electronic implants to directly convert wireless digital information into stimuli compatible with the senses. The average citizen possesses visual augmentations which allow them to directly browse the internet via voice command. More complex technology delves deeper, creating a sort of sixth sense whereby users can engage a network through thought command. Some individuals, especially accident victims with the means to afford it, might have their entire bodies replaced by neurally triggered machine components.

Ghost in the Shell has remained a uniquely relevant franchise in science fiction because it got so many ideas right. In 1989, at a time when internet was still a novelty of college libraries, the manga offered a world of total connectivity, where every human and device belonged to a global network. In 2002, Stand Alone Complex introduced the Laughing Man, and shortly afterwards the real world knew an equivalent. Whether this bodes well for the franchise’s dabblings into cyborg technology, only time can tell, but history has certainly made an inherently fascinating fictional world all the more compelling. In the Ghost in the Shell universe, science has fully bridged the gap between computers and neural systems, allowing electronic implants to directly convert wireless digital information into stimuli compatible with the senses. The average citizen possesses visual augmentations which allow them to directly browse the internet via voice command. More complex technology delves deeper, creating a sort of sixth sense whereby users can engage a network through thought command. Some individuals, especially accident victims with the means to afford it, might have their entire bodies replaced by neurally triggered machine components.