First released in 1970, Airport is a real time capsule.

As one can guess from the title, it takes place over 12 hours at an airport. The airport in question is a fictional one, Chicago’s Lincoln International Airport. Over the course of one night, almost everything that can happen does happen.

A sudden snowstorm causes almost all of the other airports in the midwest to shut down for the night. On Lincoln’s Runway 29, one of the airplanes gets stuck in the show when it lands. No one is hurt but, until Joe Patroni (George Kennedy) and his men can dig out and move that plane, no one is going to be able to land on 29.

Runway 22 is still open but the homeowners association is currently picketing the airport to protest the amount of noise pollution that is caused whenever airplanes use Runway 22. Using 22 in the middle of the night is sure to prove their point and make trouble for the airport. Mel Bakersfield (Burt Lancaster), the airport manager, thinks that the only solution is to buy up all of the land around the airport but the Board of Commissioners disagrees. Mel says that airports have to adjust to changing times but no one is willing to put up the money.

Mel is unhappily married to the wealthy and socially ambitious Cindy (Dana Wynter), who is not happy to learn that, due to the storm, Mel is going to miss an important dinner party. Tanya Livingston (Jean Seberg), head of customer relations for Trans Global Airlines, is in love with Mel but Mel isn’t the type to cheat, even if his marriage is troubled.

On the other hand, Mel’s brother-in-law, pilot Vernon Demerest (Dean Martin, the hippest pilot in the sky), has absolutely no problem cheating on his wife (Barbara Hale). Vernon is currently having an affair with flight attendant, Gwen Meighen (Jacqueline Bisset). When Gwen tells Vernon that she’s pregnant, Vernon says that “it” can be taken care of in Sweden. Gwen says that she wants to have the baby.

Meanwhile, Ada Quonsett (Helen Hayes, who won an Oscar for her performance here) is an elderly woman who has developed an addiction to stowing away on flights. She manages to sneak onto a plane flying to Rome, the same plane on which Vernon is the co-pilot. (Technically, Vernon is on the plane to evaluate the captain, who is played by Barry Nelson. Yes, the same Barry Nelson who played Jimmy Bond in 1954’s Casino Royale and Mr. Ullman in The Shining.) Ada ends up sitting next to a nervous man named D.O. Guerrero (Van Heflin). Having failed as a businessman, Guerrero has a bomb in his briefcase and is planning on blowing himself and the airplane up so that his wife (Maureen Stapleton) can receive an insurance payment.

Seriously, that’s a lot of drama! It seems like this airport has a little bit of everything! But you know what this airport doesn’t have? It doesn’t have the TSA groping people and telling them what they can and cannot take on the plane with them. It doesn’t have the endless lines full of tired travelers who just want to be allowed to get on with their business. It doesn’t have the suspicious atmosphere that has become a part of modern air travel. Compared to the average airport experience of 2026, the movie’s airport is a paradise, full of people who are working hard, who are polite to each other, and who all seem to know what they’re doing. I’d take the drama of 1970’s Airport over the reality of a modern airport any day.

Airport is very much a celebration of competent people getting the job done. On the whole, we really don’t learn much about the characters played by Burt Lancaster, Dean Martin, Jean Seberg, Barry Nelson, and George Kennedy but we definitely learn that they’re all very good at their jobs. Even Helen Hayes’s stowaway is meant to be likable precisely because she is so good at stowing away. The only person who is portrayed as being a failure as Van Heflin’s D.O. Guerrero and he’s so upset about not being good at his job that he decides to blow himself up. Though the film is full of split screens and dialogue that was probably risqué by the standards of a 1970 studio film, one gets the feeling that Airport probably felt old-fashioned even when it was first released. One can only imagine what George Kennedy’s hard-working Joe Patroni would have thought about the characters in a film like Easy Rider. About as close as Airport gets to the counterculture is Dean Martin mockingly calling Burt Lancaster “dad” while telling him to get his favorite runway cleared. This is a film where even Dean Martin is a stickler for regulations.

Based on a best-selling novel, Airport is often listed as being one of the worst films to ever be nominated for best picture. And …. well, okay, it’s definitely not a great film, especially when compared to some of the other films of the early 70s. The film was the highest grossing film of 1970 and that, more than anything, probably explains why it was nominated. Airport moves at a very deliberate pace and and visually, it is pretty flat. It looks like a competently made television pilot. When I first did a capsule review of Airport in 2010, I was fairly harsh towards it. I have to admit, though, that when I recently rewatched the film, I actually kind of liked it. Compared to today’s world, there’s something comforting about the competence of the characters in Airport. Airport has its flaws and it definitely should not have been nominated for 11 Oscars but it presents a world that seems almost cozy compared to what we have to deal with nowadays.

Dean Martin as a pilot? Helen Hayes as a chatty stowaway? George Kennedy chewing on an unlit cigar and complaining to Burt Lancaster about how incompetent the TGA pilots are? Hey, why not? If it means not having to deal with the TSA and knowing that everyone is dedicated to getting me to where I’m going in comfort, I’m all for taking my next flight out Lincoln International.

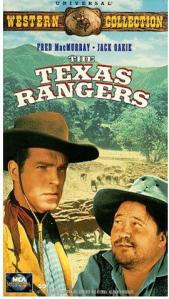

Sam (Lloyd Nolan), Jim (Fred MacMurray), and Wahoo (Jack Oakie) are three outlaws in the old west. Wahoo works as a stagecoach driver and always lets Sam and Jim know which coaches will be worth holding up. It’s a pretty good scam until the authorities get wise to their scheme and set out after the three of them. Sam abandons his two partners while Jim and Wahoo eventually end up in Texas. At first, Jim and Wahoo are planning to keep on robbing stagecoaches but then they realize that they can make even more money as Texas Rangers.

Sam (Lloyd Nolan), Jim (Fred MacMurray), and Wahoo (Jack Oakie) are three outlaws in the old west. Wahoo works as a stagecoach driver and always lets Sam and Jim know which coaches will be worth holding up. It’s a pretty good scam until the authorities get wise to their scheme and set out after the three of them. Sam abandons his two partners while Jim and Wahoo eventually end up in Texas. At first, Jim and Wahoo are planning to keep on robbing stagecoaches but then they realize that they can make even more money as Texas Rangers.