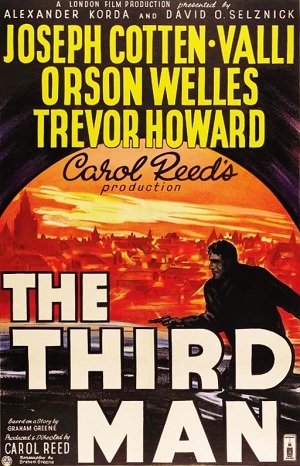

For some reason, certain people seem to feel the need to try to reduce what Orson Welles accomplished with 1941’s Citizen Kane.

In 1971, the famous film critic Pauline Kael published an essay called Raising Kane, in which she argued that screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz deserved the majority of the credit for Citizen Kane. This was Kael’s shot at rival Andrew Sarris and his embrace of the auteur theory. (1971 was the same year that Kael described Dirty Harry as being a “fascist work of art” so I guess even the best film critics can have a bad year.) David Fincher’s father, after reading Kael’s essay, wrote the screenplay for Mank, which not only made the case that Mankiewicz deserved the credit but which portrayed Orson Welles in such a negative fashion that you really did have to wonder if maybe Orson had owed old Jack Fincher money or something. Herman J. Mankiewicz himself always claimed that he deserved the majority of the credit for Citizen Kane but then he would, wouldn’t he?

The truth of the matter is that Mankiewicz did write the screenplay for Citizen Kane and he did base the character of Charles Foster Kane on William Randolph Hearst and the character of Kane’s second wife on Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies. There’s some debate over how much of the film’s narrative structure belongs to Mankiewicz and how much of it was a result of Welles rewriting the script. Mankiewicz played his part in the making of Citizen Kane but he played that part largely because Orson Welles allowed him to. Like all great directors, Welles surrounded himself with people who could help to bring his vision to life. (That’s something that would think David Fincher, of all people, would understand. Aaron Sorkin may have written The Social Network but the reason why the film touched so many is because it was a David Fincher film.)

Make no mistake about it. Citizen Kane is Orson Welles’s vision and Welles is the one who deserves the majority of the credit for the film. The themes of Citizen Kane are ones to which Welles would frequently return and the cast, all of whom bring their characters to vivid life, is made up of largely of the members of Welles’s Mercury Theatre. The tracking camera shots, the dark cinematography, and the satiric moments are all pure Welles. As the Fincher film argues, Mankiewicz may have very well meant to use the film to attack Hearst for his personal hypocrisy and for opposing the political ambitions of Upton Sinclair. If so, let us be thankful that Orson Welles, as a director, was smart enough to realize that such didacticism is often deadly dull.

And there’s nothing dull about Citizen Kane. It’s a great film but it’s also an undeniably fun film, full of unforgettable imagery and scenes that play like their coming to us in a dream. It’s a film that grabs your interest and proves itself to be worthy of every minute that it takes to watch it. I was lucky enough to first see Citizen Kane at a repertory theater and on the big screen and really, that’s the best way to watch it. It’s a big film that’s full of bigger-than-life characters who are ultimately revealed to be full of the same human longings and regrets as all of us. As a young man, the fabulously wealthy Charles Foster Kane thinks that it would be “fun” to run a newspaper. Later, he thinks that he’s found love by marrying the niece of the President. He runs for governor of New York and, watching Welles in these scenes, you can see why FDR tried to recruit him to run for the Senate. Welles has the charisma of a born politician. When Welles first meets Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore) it’s easy to laugh. The great man has just been splashed by a taxi. Susan laughs but then winces in pain due to a tooth ache. Later, Kane insists on trying to turn her into an opera star. He runs a negative review written by his friend (Joseph Cotten) and then he promptly fires him. As in all of Welles’s films, it’s all about personal loyalty. Kane may betray his wife and the voters but he’s ultimately just as betrayed by those around him. In the end, you get the feeling that Kane was desperately trying to not be alone and yet, that’s how he ended up.

There are so many stand-out moments in Citizen Kane that it’s hard to list them all. The opening — MIGHTY XANADU! — comes to mind. The satirically overdramatic newsreel is another. (Citizen Kane can be a very funny film.) Joseph Cotten’s performance continues to charm. Orson Welles’s performance continues to amaze. Who can forget Agnes Moorehead as Kane’s mother or Everett Sloane as Mr. Bernstein, haunted by that one woman he once saw on a street corner? Myself, I’ve always liked the performances of Ray Collins (as the sleazy but strangely reasonable Boss Gettys), Paul Stewart (as the subtly menacing butler), and Ruth Warrick (as Kane’s first wife). Mankiewicz may have put the characters on paper but Welles is the one who selected the amazing cast that brought them to life.

Citizen Kane was nominated for nine Oscars and it won one, for the screenplay written by Welles and Mankiewicz. Best Picture went to How Green Was My Valley. When was the last time anyone debated who should be given credit for that movie?