What’s an Insomnia File? You know how some times you just can’t get any sleep and, at about three in the morning, you’ll find yourself watching whatever you can find on cable or streaming? This feature is all about those insomnia-inspired discoveries!

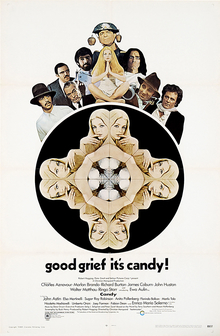

If you find yourself having trouble getting to sleep tonight, you can always pass the time by watching the 1968 film, Candy. It’s currently on Tubi.

Based on a satirical novel by Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg, Candy follows Candy Christian (Ewa Aulin), a naive teenager from middle America as she has a number of increasingly surreal adventures, the majority of which end with her getting sexually assaulted by one of the film’s special guest stars. It’s very much a film of the 60s, in that it’s anti-establishment without actually seeming to know who the establishment is. It opens with a lengthy sequence that appears to be taking place in outer space. It ends with an extended sequence of Candy walking amongst the film’s cast and a bunch of random hippies. Director Christian Marquand appears as himself, directing the film. Yep, this is one of those films where the director and the film crew show up and you’re supposed to be say, “Far out, I didn’t realize I was watching a movie, man.”

The whole thing is a bit of a misfire. The novel was meant to be smut that satirized smut. The film isn’t really clever enough to work on any sort of real satirical level. As was the case with a lot of studio-made “psychedelic” films in the 60s, everything is a bit too obvious and overdone. Casting the Swedish Ewa Aulin as a character who was meant to represent middle America was just one of the film’s missteps. Based on The Graduate, Mike Nichols probably could have made a clever film out of Candy. The French Christian Marquand, a protegee of Roger Vadim’s, can not because he refuses to get out of the film’s way. It’s all jump cuts, flashy cinematography, and attempts to poke fun at American culture by someone who obviously knew nothing about America beyond the jokes told in Paris.

That said, the main reason that anyone would watch this film would be for the collection of guest stars who all show up and try to take advantage of Candy. Richard Burton plays an alcoholic poet named MacPhisto and his appearance goes on for far too long. (Burton, not surprisingly, appears to actually be drunk for the majority of his scenes.) Ringo Star — yes, Ringo Starr — plays a Mexican gardener who assaults Candy after getting turned on by the sight of MacPhisto humping a mannequin. When Emmanuel’s sisters try to attack Candy, she and her parents escape on a military plane that is commanded by Walter Matthau. Landing in New York, Candy’s brain-damaged father (John Astin) is operated on by a brilliant doctor (James Coburn) who later seduces Candy after she faints at a cocktail party. Candy’s uncle (John Astin, again) also tries to seduce Candy, leading to Candy getting lost in New York, meeting a hunchback (Charles Aznavour), and then eventually ending up with a guru (Marlon Brando). Candy’s adventures climax with a particularly sick joke that requires a bit more skill to pull off than this film can afford.

If you’re wondering how all of these famous people ended up in this movie, you have Brando to thank (or blame). Christian Marquand was Brando’s best friend and Marlon even named his son after him. After Brando agreed to appear in the film, the rest of the actors followed. Brando, Burton, and Coburn received a share of the film’s profits and Coburn later said that his entire post-1968 lifestyle was pretty much paid for by Candy. That seems appropriate as, out of all the guest stars, Coburn i the only one who actually gives an interesting performance. Burton is too drunk, Matthau is too embarrassed, Starr is too amateurish, and Brando is too self-amused to really be interesting in the film. Coburn, however, seems to be having a blast, playing his doctor as being a medical cult leader.

Candy is very much a film of 1968. It has some value as a cultural relic. Ultimately, it’s main interest is as an example of how the studios tried (and failed) to latch onto the counterculture zeitgeist.

Previous Insomnia Files:

- Story of Mankind

- Stag

- Love Is A Gun

- Nina Takes A Lover

- Black Ice

- Frogs For Snakes

- Fair Game

- From The Hip

- Born Killers

- Eye For An Eye

- Summer Catch

- Beyond the Law

- Spring Broke

- Promise

- George Wallace

- Kill The Messenger

- The Suburbans

- Only The Strong

- Great Expectations

- Casual Sex?

- Truth

- Insomina

- Death Do Us Part

- A Star is Born

- The Winning Season

- Rabbit Run

- Remember My Name

- The Arrangement

- Day of the Animals

- Still of The Night

- Arsenal

- Smooth Talk

- The Comedian

- The Minus Man

- Donnie Brasco

- Punchline

- Evita

- Six: The Mark Unleashed

- Disclosure

- The Spanish Prisoner

- Elektra

- Revenge

- Legend

- Cat Run

- The Pyramid

- Enter the Ninja

- Downhill

- Malice

- Mystery Date

- Zola

- Ira & Abby

- The Next Karate Kid

- A Nightmare on Drug Street

- Jud

- FTA

- Exterminators of the Year 3000

- Boris Karloff: The Man Behind The Monster

- The Haunting of Helen Walker

- True Spirit

- Project Kill

- Replica

- Rollergator

- Hillbillys In A Haunted House

- Once Upon A Midnight Scary

- Girl Lost

- Ghosts Can’t Do It

- Heist

- Mind, Body & Soul