Welcome to Fort Apache, The Bronx.

Shot on location, the 1981 film of the same name takes place in one of the toughest police precincts in New York City. The film opens with a prostitute (Pam Grier) walking up to a police car in the middle of the night and promptly gunning down the two cops inside. (The scene emphasis on the blood splattering in the squad car makes it all the more disturbing and frightening.) As soon as the cops are dead, people come out of the shadows and immediately start going through their pockets, collecting everything that they can.

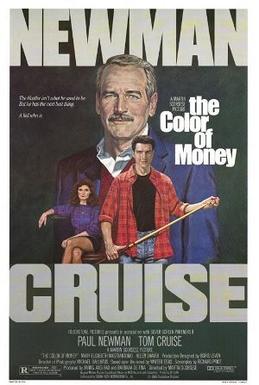

Why were the cops killed? There is no real motive, beyond Grier’s prostitute being high on drugs and enjoying the kill. Indeed, we know from the start that Grier is the killer but the cops investigating the case continually ignore her, despite the fact that she’s always wandering around in the background. (Grier is perfectly frightening in the nearly silent role.) The new captain of the precinct, a by-the-book type named Dennis Connolly (Ed Asner), assumes that the killing must have been an organized assassination and he is soon ordering his cops to arrest and interrogate almost anyone that they see. If someone jaywalks, Connolly wants them in the back of a squad car so that they can be interrogated. He offers to give the men two weeks of extra vacation time for every lead that they find. When veteran detective John Joseph Vincent Murphy III (Paul Newman) says that the reward is going to do more damage than good, Connolly dismisses his concerns. Connolly is convinced that he knows how to run the precinct. He views the people who live in the Bronx as being enemies who have to be tamed and controlled. Murphy, who comes from a long line of cops, believes in working with the community as opposed to going strictly by the book.

It’s an episodic film, following Murphy and his partner, Corelli (Ken Wahl), as they try to keep the peace in a neighborhood full of empty lots, abandoned buildings, and horrific poverty. (The film is all the more effective for having actually been shot on location. Looking at the scenery in which everyone is living and working, it’s easy to understand why tempers get so easily frayed.) Corelli is ambitious. Murphy is cynical. When Murphy meets a nurse (Rachel Ticotin), it seems like love at first sight. They’re both survivors of the toughest city in America. But the nurse has a secret of her own. There’s a lot of stories that are told in Fort Apache, The Bronx but few of them have a happy ending.

It’s an effective film, though the structure is occasionally a bit too loose and the generic “cop music” on the soundtrack sometimes makes it seem as if the viewer is watching a cop show on one of the nostalgia channels. The film works because it allows the Bronx itself to be as important a character as the cops played by Newman, Asner, and Wahl. There’s a grittiness to the film that overcomes even the occasional melodramatic moment. In the end, the film suggests that, while cops come and go, the precinct will always remain the same. Killing two drug dealers just allows two more to move in. Reporting on a bad cop, like the one played in the film by Danny Aiello, will only lead to the ostracization of a good cop. To the film’s credit, neither Newman nor Asner are portrayed as being totally correct or totally wrong in their different approaches to police work. Newman is correct about Asner’s heavy-handed tactics creating mistrust and resentment in the community. Asner, however, has a point when he says that a cop killer cannot be allowed to go unpunished.

Paul Newman gives a great performance as Murphy, a role that a lesser actor would have turned into a cliche. Murphy is the latest in a long line of cops and he’s on the verge of abandoning the family business. Newman does a good job of portraying not only Murphy’s burnout but also how his affair with the nurse briefly inspires him to believe that he still might actually be able to make a difference in the world. The film ends on an ambiguous note, one that leaves you with the impression that Murphy couldn’t stop being a cop if he tried. The job may be burning him out but it’s still the only thing he knows.

Fort Apache, The Bronx is not an easy movie to find. Though it did well at the box office (and reportedly inspired shows like Hill Street Blues and NYPD Blue), the film was also controversial because of the way the Bronx was portrayed. While it’s not currently streaming or even available to rent on any of the major sites, I did find a good, age-restricted upload on YouTube. Look for it before someone takes it down.