Michael Mann has always been in the forefront of experimenting and trying out new film techniques and styles to tell his stories. 2003’s Collateral was a veritable masterpiece of directing of a modern, urban noir. He even made Tom Cruise very believable as a sociopathic character. In 2006, Michael Mann followed up Collateral with another trip down the darkside of the law and crime. Taking a concept he made into a cultural phenomenon during the mid 80’s, Mann reinvents the show Miami Vice from the pastel colors, hedonistic and over-the-top drug-culture Miami of the 1980’s to a more down, dirty and shadowy world of the new millenium where extremes by both the cops and the criminals rule the seedy, forgotten side of the city.

Michael Mann’s films have always dealt with the extremes in its characters. Whether its James Caan’s thief character Frank in Thief, the dueling detective and thief of Al Pacino and Robert DeNiro in Heat, up to Foxx and Cruise’s taxi driver and assassin in the aforementioned Collateral. They all have had one thing in common. They’re individuals dedicated to their chosen craft. Professional in all respect and so focused to doing their job right that they’ve crossed the line to obsession. It is this obsession and how it governs everything they do which almost makes it into their own personal form of drug.

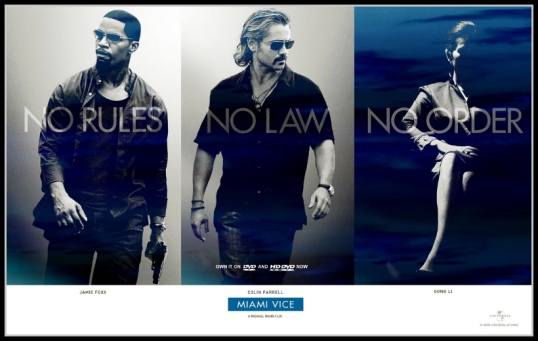

This theme continues in Mann’s film reboot of his TV series Miami Vice. The characters remain the same. There’s still the two main characters of Vice Detectives Sonny Crockett and Ricardo Tubbs. This time around these titular characters were played by Colin Farrell (in a look that echoes Gregg Allman more than Don Johnson) and Jamie Foxx. From the first moment the first scene suddenly appears all the way through to the final fade to black in the end of the film, the audience was thrust immediately into the meat of the action. Mann dispenses with the need for any sort of opening credits. In fact, the title of the film doesn’t appear until the end of the film and the same goes for the names of all involved. I thought this was a nice touch. It gave the film a stronger realism throughout.

The film’s story was a mixture of past classic episodes rolled into one two-hour long film with the episode “Smuggler’s Blues” being the main influence on the story. The glamour and glitz that were so prevalent in the original series does show up in the film, but it’s not used too much that it turned the characters of Crockett, Tubbs and the rest of the cast into caricatures. The glamour seems more of a thin veneer to hide the danger inherent in all the parties involved. These people were all dangerous from the cops to the criminals. There’s a lot of the so-called “gray areas” between what makes a cop and what makes a criminal. Mann’s always been great in blurring those lines and in showing that people on either side of the line have much more in common than they realize.

Miami Vice‘s story doesn’t leave much for back story exposition for the main leads. Michael Mann takes the minimalist approach and just introduces the characters right from the beginning with nothing to explain who they were outside of the roles they played — whether they were law-enforcement or drug dealers. The script allows for little personal backstory and instead lets the actors’ performance show just what moves, motivates and inspires these characters. Again, Jamie Foxx steals the film from his more glamorous co-star in Colin Farrell. Farrell did a fine job in making Crockett the high-risk taking and intense half of the partnership, but Foxx’s no-nonsense, focused intensity as Tubbs was the highlight performance throughout the film.

The rest of the cast do a fine job in the their roles. From Gong Li as Isabella, the drug-lord’s moll who also double’s as his organization’s brains behind the finances to Luis Tosar as the mastermind drug kingping Arcángel de Jesús Montoya. Tosar as Montoya also does a standout performance, but was in the screen for too less a time. Two other players in the film I have to make mention of were John Ortiz as Jose Yero who was Montoya’s machiavellian spymaster and Tom Towles in a small, but scary role as the leader of the Aryan Brotherhood gang hired by Yero to be his Miami enforcers. Both actors were great in their supporting role and more than held their own against their more celebrated cast mates.

This film wouldn’t be much of a police crime drama if it was all talk and no action. The action in Miami Vice comes fast and tight. Each scene was played out with a tightness and intensity which prepped the audience to the point that the violence that suddenly arrives was almost a release. Everyone knew what was coming and when the violence and action do arrive it goes in hard and fast with no use of quick edits, slow-motion sequences or fancy camera angles and tricks like most action films. Instead Michael Mann continues his theme of going for realism even in these pivotal moments in the film.

The shootouts doesn’t have the feel of artificiality. The gunshots inflicted on the people in the film were brutal, violent and quick. The camera doesn’t linger on the dead and wounded. These scenes must’ve taken only a few minutes of the film’s running time, but they were minutes that were executed with Swiss-like precision. The final showdown at an empty lot near the Miami docks was organized chaos with the scene easy to follow yet still keeping a sense of anarchy to give the whole sequence a real sense of “in the now”.

The look of the film was where Mann’s signature could be seen from beginning to end. He started using digital cameras heavily in Collateral. His decision to use digital cameras for that film also was due to a story mostly set at night. The use of digital allowed him to capture the deepest black to off-set the grays and blues of Los Angeles at night. Mann does the same for Miami Vice, but he does Collateral one better by using digital cameras from beginning to end. Digital lent abit of graininess to some scenes, but it really wasn’t as distracting as some reviewers would have you believe. In fact, it made Miami Vice seem like a tale straight out of COPS or one of those reality police shows.

Michael Mann stretches the limits of what his mind and technology could accomplish when working in concert. Mann’s direction and overall work in Miami Vice could only be described as being as focused and obsessive over the smallest detail as the characters in his films. This is a filmmaker who seem to want nothing but perfection in each scene shot.

With Miami Vice, Michael Mann has done the unthinkable and actually made a film adaptation of a TV show look like an art-film posing as a tight police drama. Everyone who have given the film a less than stellar review seem to have done so because Mann didn’t use the 80’s imagery and sensibilities from the original show. There were no pastel designer clothes and homes. There was no pet alligator and little friendly banter and joking around. Mann goes the other way and keeps the mood deadly serious. This was very apropo since the two leads led mortally dangerous lives as undercover agents who could die at the slightest mistake. The fun and jokes of the original series would’ve broken the mood and feel of this film. I, for one, am glad Mann went this route and not paid homage to the original series. This some saw as a major flaw, but I saw it as the main advantage in keeping Miami Vice from becoming a self-referential film bordering on camp.

Miami Vice was a finished product thats smart, stylish, and innovative crime drama. This was a film that people would either love despite some of the flaws, or one people would hate due to not being like the original TV series. Those who decide to skip watching Miami Vice because of the latter would miss a great film from one of this generation’s best directors. Those who do give this version of Miami Vice a chance would be rewarded with a great tale of cops and criminals and the obsession they have in their set roles.