I’m one of the biggest fans of the San Francisco 49ers. In my 52 years on earth, I’ve been able to celebrate a lot of Super Bowl Sundays that have featured my team. We even won 5 of those Super Bowls. The problem is that all five of those victories came before I reached the age of 22. Over the last 30 years, we’ve reached another 3 Super Bowls and lost each one in heartbreaking fashion. I thought I’d share my main memories of each of those games today!

Super Bowl XVI — January 24, 1982

The 49ers won their first Lombardi trophy when they edged the Cincinnati Bengals 26-21 in a gritty, hard-fought battle at the Pontiac Silverdome. This kicked off the 49ers ‘80’s dynasty where the would win four Super Bowls during the decade. For an eight year old Brad, what I remember the most personally during that year was not the Super Bowl, but rather the victory over the Dallas Cowboys in the NFC Championship, when Joe Montana threw the ball and Dwight Clark made “the catch!” It has justly retained its place over the years as one of the great plays in NFL history.

Super Bowl XIX — January 20, 1985

San Francisco kicked the Miami Dolphins butts, 38–16, in their own backyard, showcasing a team firing on all cylinders and carving their name into NFL lore. My brother Donnie was a huge fan of the Dolphins back at this time. I was eleven years old and he was twelve, and I remember I didn’t want to rub it in, because I didn’t want to hurt his feelings. When I think of that game, I think of Montana throwing TD passes to recent Hall of Fame inductee Roger Craig!

Super Bowl XXIII — January 22, 1989

In a classic showdown in Miami, the 49ers rallied late to beat the Bengals 20–16, a game punctuated by clutch plays and a finish that echoed their championship pedigree. I had reached the age of 15 when the Niners beat the Bengals for a 2nd time in the decade. When I think of this game, I think of Jerry Rice being unstoppable, John Taylor catching the winning TD pass from Montana with 34 seconds to play, and I think of the story Montana told about John Candy as the last drive was about to start. It was awesome stuff!

Super Bowl XXIV — January 28, 1990

San Francisco exploded in New Orleans, routing the Denver Broncos 55–10 in one of the most dominant performances in Super Bowl history… a statement that this franchise was at its peak. I was 16 years old when this game was played. I honestly don’t remember that much of the game itself, because I was making out with my girlfriend for most of the game. I do remember paying enough attention to know that we were kicking butt. Once our dominance was firmly established, most of my focus was elsewhere!

Super Bowl XXIX — January 29, 1995

In Miami, the 49ers put the exclamation point on their ‘90s success with a 49–26 victory over the San Diego Chargers, racking up points in every quarter and leaving no doubt who ruled that season. This was one of my favorite Super Bowls and my favorite team’s last win. I was 21 years old and had been married for less than a month. We had a Super Bowl party with friends, and Steve Young threw six TD passes, a record that still stands, as the Niners routed the Chargers. The grilled hamburgers tasted great that night as Young got the Montana legacy “monkey off of his back” and wrote his own Canton story.

Super Bowl XLVII — February 3, 2013

After years away from football’s biggest stage, San Francisco returned but fell just short, losing a tight 31–34 to the Baltimore Ravens in a game defined by momentum swings and near misses. Eighteen years after the 49ers last Super Bowl, we finally made it back. Colin Kaepernick, Frank Gore, Michael Crabtree and Vernon Davis seemed unstoppable going into the Super Bowl, but Joe Flacco and the Ravens had other plans. After falling way behind, a stadium power outage wasn’t enough to save my team as we fell just short in the “Har-Bowl.” The youth group from our church was at our house that night, so I tried to be on my best behavior, but it wasn’t easy when the refs didn’t call a clear holding penalty on the Ravens near the end. This was also my first Super Bowl with my son who was 13 at the time.

Super Bowl LIV — February 2, 2020

In Miami Gardens, the Chiefs outpaced the 49ers 31–20, capping a back-and-forth affair that saw San Francisco’s defense bend and an explosive Kansas City offense take control in the second half. Recently divorced, I watched this game with my 13 year old daughter at Buffalo Wild Wings. It was another heartbreaking loss, where we were ahead by 10 points in the fourth quarter before falling apart. I was trying to enjoy the time with my daughter, and for the most part I was successful, but it still hurt as we lost again.

Super Bowl LVIII — February 11, 2024

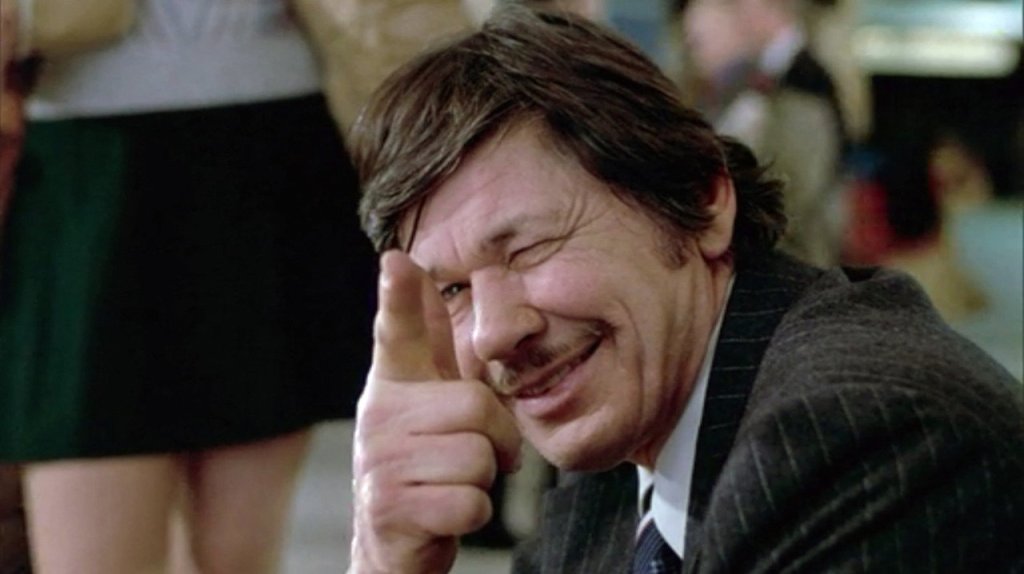

In a heartbreaker at Allegiant Stadium, the 49ers fought Kansas City to the wire but fell 25–22 in overtime… a testament to grit even in defeat on football’s grandest stage. As a 50 year old man, this Super Bowl meant something different to me than any Super Bowl before. My wife and I went to my mom and dad’s house and watched the game. My son also joined us. I really just wanted to watch the 49ers win a Super Bowl with my dad and my son. My son, also a huge 49ers fan, had never seen them win the ultimate championship. I thought it would be the perfect night to celebrate. Unfortunately, Brock Purdy and the Niners came up just short against Patrick Mahomes again in overtime. It was another punch to the gut.

With that said, however, and with a little time, that Super Bowl in 2024 is so meaningful to me. My dad, my son and I watched every play together in complete unison as we pulled for the Niners. The night may not have ended the way we wanted it to, but it was still a wonderful and special night. The picture I share here was from that night as the game was about to get started. Nothing that’s meaningful comes without a little bit of pain, and that night was one of the most meaningful of my last few years!

Tonight, I’ll watch the Super Bowl, but I won’t be with my Dad or my son. Either the Seahawks or Patriots will win, but in a few days I won’t ever care again. It does give me some peace knowing that out there somewhere, Dads and sons will be living and dying on every play. That won’t be us tonight, but it wasn’t that long ago that it was!