“Nothing’s ever just a conversation with you, John.” — Sofia Al-Azwar

John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum launches straight from the previous installment’s shocking finale, hurling John into a frantic dash through New York’s underbelly as a $14 million bounty turns every shadow into a threat. This chapter dials the franchise’s signature intensity even higher, plunging you into an assassin underworld bound by ironclad rules that start to fracture under pressure. The action explodes with creative savagery, though the storyline sometimes buckles beneath its ambitions, offering a pulse-pounding yet slightly bloated addition to the saga.

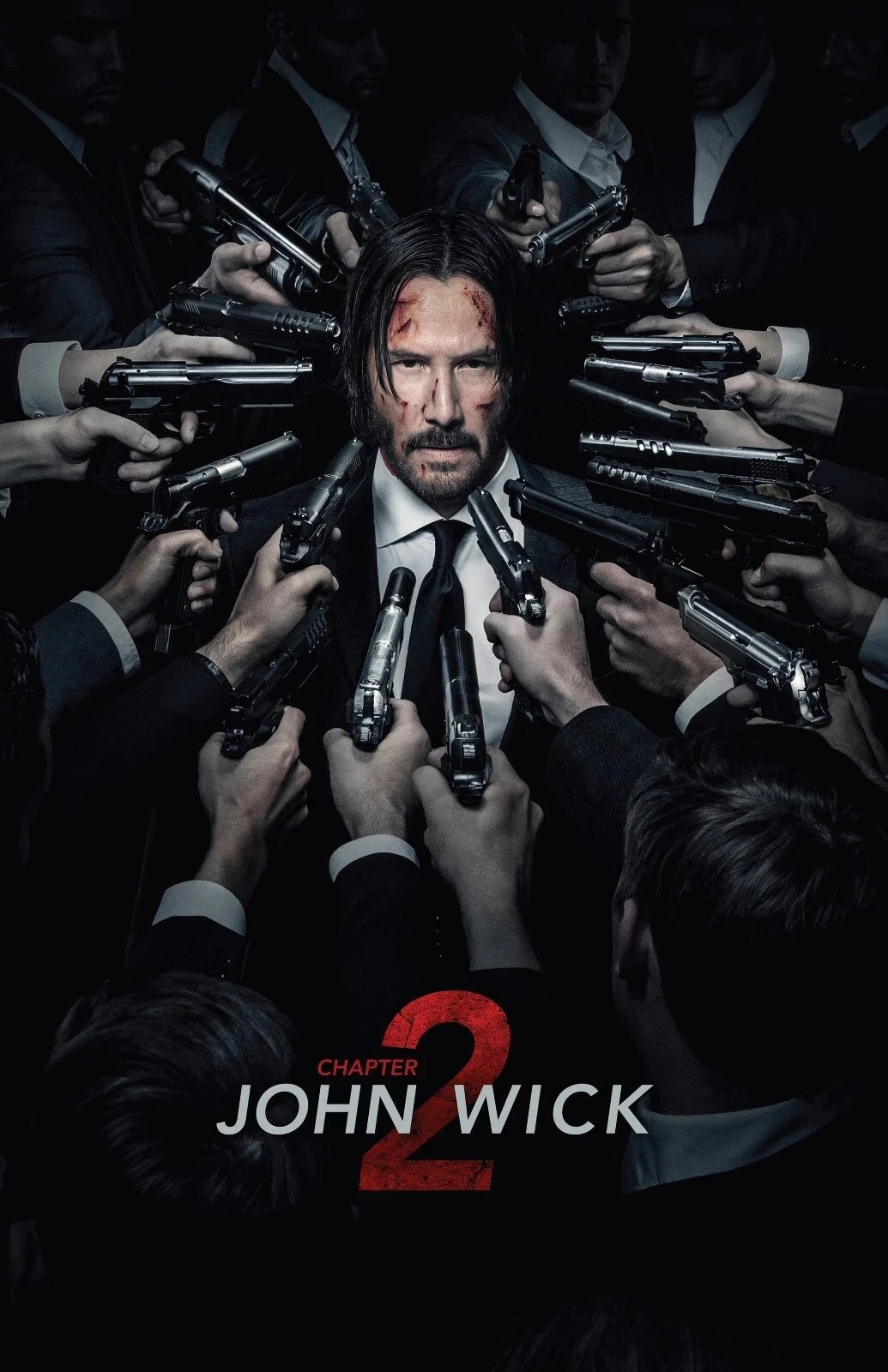

The movie opens with John scrambling through New York streets, his excommunicado status ticking down like a bomb. He’s got one hour before every killer in the city turns on him, and boy, do they. Keanu Reeves is back in top form, looking battered but unbreakable, his puppy-dog eyes conveying more grief and determination than any monologue could. The film’s Latin subtitle, Parabellum—meaning “prepare for war”—sets the tone perfectly as John grabs weapons from the oddest places, like a horse stable or a knife shop where he gets to use blades almost like guns with each throw.

What makes this entry stand out is how it expands the Wick-verse without losing that gritty intimacy. We dive deeper into the High Table’s bureaucracy, with the Adjudicator (Asia Kate Dillon) showing up as this cold, efficient enforcer who judges allies like Winston (Ian McShane) and Charon (Lance Reddick) for helping John. It’s a smart addition, adding layers to the rules that have always governed this world—markers, blood oaths, no business on Continental grounds. Halle Berry pops in as Sofia, an old flame running a Moroccan palace full of attack dogs, leading to one of the film’s wildest sequences where pooches tear into bad guys alongside John. Mark Dacascos as Zero, the sushi-loving villain who’s bald and sports a penchant for movie quotes, brings some quirky charm, even if he’s no Santino from Chapter 2.

Director Chad Stahelski, a former stuntman himself, continues to treat action like high art, and man, does Chapter 3 flex its muscles here harder than ever. The choreography is balletic and brutal, blending gun fu with knives, swords, and even books—there’s a library fight where John uses a volume as a shield and club, then politely reshelves it, which is peak Wick weirdness. Fights escalate from motorcycle sword duels slicing through rainy streets to hall-of-mirrors mayhem that nods to Enter the Dragon, with reflections multiplying the chaos into a dizzying ballet of blades. Indonesian martial arts legends Cecep Arif Rahman and Yayan Ruhian, The Raid 2 alumni who make their franchise debut here, light up the massive finale melee, trading blows with John in a flurry of fists, elbows, and blades that feels like a love letter to silat and caps the chaos perfectly.

Every sequence feels meticulously planned, relying on practical stunts that make CGI-heavy blockbusters look lazy and fake—think real falls, real crashes, real bone-crunching impacts that leave you wincing. The gun fu style—precise headshots amid flips, slides, and reloads—never gets old, evolving with fresh twists like pencil kills upgraded to book barrages or horse-mounted shootouts. The film’s true strength lies in these set pieces: they’re not just fights, they’re symphony-like spectacles where camera work syncs breathlessly with the violence, spatial awareness stays razor-sharp so you track every bullet and block, and the escalation feels organic, building from claustrophobic knife scraps to epic rooftop brawls. It’s the kind of action that honors the genre’s legends while pushing boundaries, making you forget any plot gripes amid the sheer kinetic joy.

That said, it’s not all flawless, and one drawback from Chapter 2 creeps back in here: the film leans heavily into more world-building of its universe, which puts character development on the back burner. John’s arc—fighting to earn back his freedom—repeats beats from the previous entry, and some twists, like Winston’s apparent betrayal, land more as fan service than emotional gut-punches. At 131 minutes, it drags in spots, especially during quieter moments that try to humanize John but end up repetitive, while the dialogue stays sparse and stylized, leaving characters like the Elder (Saïd Taghmaoui) feeling underdeveloped. But then again, the franchise has staked its claim on being action-focused from the jump, so if fans are bought into this wild ride by now, they’re probably here for the balletic bloodshed over deep psychology anyway—it’s like the film loves its assassins’ code more than fleshing out motivations beyond revenge.

Visually, it’s a stunner. Dan Laustsen’s cinematography turns New York into a neon-soaked hellscape, with rain-slicked streets and ornate Continental lobbies popping in crisp 2.40:1. The Morocco desert scenes add exotic flair, though they borrow heavily from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Tyler Bates and Joel J. Richard’s score pounds with industrial electronica, syncing perfectly to the violence, while select tracks like Team Rezo’s “Pray for Kaeo” amp up horse chases. Sound design is Oscar-worthy—the thud of fists, crack of gunfire, all mixed to immerse you in the carnage.

Keanu Reeves carries it all, 54 at release but moving like a man half his age thanks to rigorous training. His physical commitment sells John’s exhaustion; you see the toll in every limp and gasp. Supporting cast shines too—McShane’s suave Winston steals scenes with dry wit, Reddick’s Charon is unflappably loyal, and Berry holds her own in dog-assisted fury. Dacascos adds levity, slicing foes with a sunny disposition, but Dillon’s Adjudicator is more menacing presence than fleshed-out foe. It’s ensemble work in service of spectacle, not drama.

For fans of the series, John Wick: Chapter 3 delivers bigger, bolder chaos that honors stunt performers as the real stars. It celebrates cinema history with nods to Buster Keaton (a horse chase echoes The General) and Hong Kong action flicks, all while pushing practical effects. Critics raved about the thrills, calling it “blissfully brutal” entertainment that shames neighbors like generic superhero fare. Audiences loved the over-the-top kills and Reeves’ stoic heroics.

To keep it fair, though, this isn’t exactly groundbreaking stuff. The simplicity that charmed in the original—a widower’s rampage—has bloated into a globe-trotting saga chasing its own tail. Female characters, while badass like Sofia, still orbit John’s story, and the violence, though stylish, borders on cartoonish excess. Some felt it lost narrative steam, prioritizing set pieces over heart, turning Wick from grieving everyman to invincible machine. Compared to Chapter 2‘s operatic betrayal, this one’s more procedural, like a video game level grind.

Ultimately, John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum is a love letter to action cinema, casual fun if you’re in for the mayhem. It’s not deep, but damn if it doesn’t make you cheer as John unleashes hell. Grab popcorn, dim the lights, and prepare for war—you won’t regret it, unless you’re after Oscar bait. Solid 8/10 for pure, delirious popcorn thrills.

Weapons used by John Wick throughout the film

- TTI STI 2011 Combat Master: Iconic pistol from the armory scene—John’s “2011” choice with optics, extended mags, and flawless reliability for extended shootouts.

- Glock 19 / 19X / 17: Multiple pickups during mint guard fights in Casablanca and Continental siege; versatile Glocks he commandeers mid-battle.

- Walther PPQ / CCP: Snagged from assassins during the motorcycle chase; quick-use comped models for on-the-run defense.

- TTI SIG-Sauer MPX Carbine: Siege standout with Trijicon MRO sight, Streamlight laser, and +11 mags—John’s signature stance shines in hallway clears.

- SIG-Sauer MPX / MPX Copperhead: Casablanca mint raid grabs; compact 9mm shredders with red dots and grips for close-quarters fury.

- Benelli M4 Super 90: Climactic Continental siege with Charon; armor-piercing slugs, extended tubes, ghost rings—devastating hallway blasts.

- Benelli M2 Super 90 (TTI Ultimate package, implied variants): Siege support; Charon favors these, John grabs similar for enforcer waves.

John Wick Franchise (spinoffs)