1970’s The Andersonville Trial takes place in one muggy military court room. The year is 1865. The Civil War is over but the wounds of the conflict are still fresh. Many of the leaders of the Confederacy are still fugitives. Abraham Lincoln has been dead for only a month. The people want someone to pay and it appears that person might be Captain Henry Wirz (Richard Basehart).

Originally born in Switzerland and forced to flee Europe after being convicted of embezzlement, Henry Wirz eventually ended up in Kentucky. He served in the Confederate Army and was eventually named the commandant of Camp Sumter, a prison camp located near Andersonville, Georgia. After the war, Captain Wirz is indicted for war crimes connected to his treatment of the Union prisoners at the camp. Wirz and his defense counsel, Otis Baker (Jack Cassidy), argue that the prison soon became overcrowded due to the war and that Wirz treated the prisoners as well as he could considering that he had limited resoruces. Wirz points out that his requests for much-needed supplies were denied by his superiors. Prosecutor Norton Chipman (William Shatner) argues that Wirz purposefully neglected the prisoners and their needs and that Wirz is personally responsible for every death that occurred under his watch. The trial is overseen by Maj. General Lew Wallace (Cameron Mitchell), the same Lew Wallace who would later write Ben-Hur and who reportedly offered a pardon to Billy the Kid shortly before the latter’s death. Wallace attempts to give Wirz a fair trial, even allowing Wirz to spend the trial reclining on a couch due to a case of gangrene. (Agck! The 19th century was a scary time!)

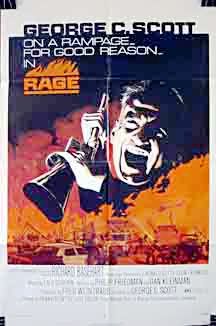

The Andersonville Trial started life as a 1959 Broadway production. On stage, George C. Scott played Chipman, an experience he described as difficult because, even though Chipman was nominally the play’s hero, Wirz was actually a much more sympathetic character. When the play was adapted for television in 1970, Scott returned to direct. Admittedly, the television version is very stagey. Scott doesn’t make much effort to open up the play. Almost all of the action is confined to that courtroom. We learn about the conditions at Fort Sumter in the same way that the judges learned about the conditions. We listen as the witnesses testify. We listen as a doctor played by Buddy Ebsen talks about the deplorable conditions at Fort Sumter. We also listen as a soldier played by Martin Sheen reports that Wirz has previously attempted to suicide and we’re left to wonder if it was due to guilt or fear of the public execution that would follow a guilty verdict. We watch as Chipman and Baker throw themselves into the trial, two attorneys who both believe that they are correct. And we watch as Wirz finally testifies and the play hits its unexpected emotional high point.

As most filmed plays do, The Andersonville Trial demands a bit of patience on the part of the viewer. It’s important to actually focus on not only what people are saying but also how they’re saying it. Fortunately, Scott gets wonderful performances from his ensemble cast. Even William Shatner’s overdramatic tendencies are put to good use. Chipman is outraged but the play asks if Chipman is angry with the right person. With many of the Confederacy’s leaders in Canada and Europe, Wirz finds himself standing in for all of them and facing a nation that wants vengeance for the death of their president. Wirz claims and his defense attorney argues that Wirz was ultimately just a soldier who followed orders, which is what soldiers are continually told to do. The Andersonville Trial considers when military discipline must be set aside to do what is morally right.

Admittedly, when it comes to The Andersonville Trial, it helps to not only like courtroom dramas but to also be a bit of a history nerd as well. Fortunately, both of those are true of me. I found The Andersonville Trial to be a fascinating story and a worthy production.