“We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection.” — Abraham Lincoln

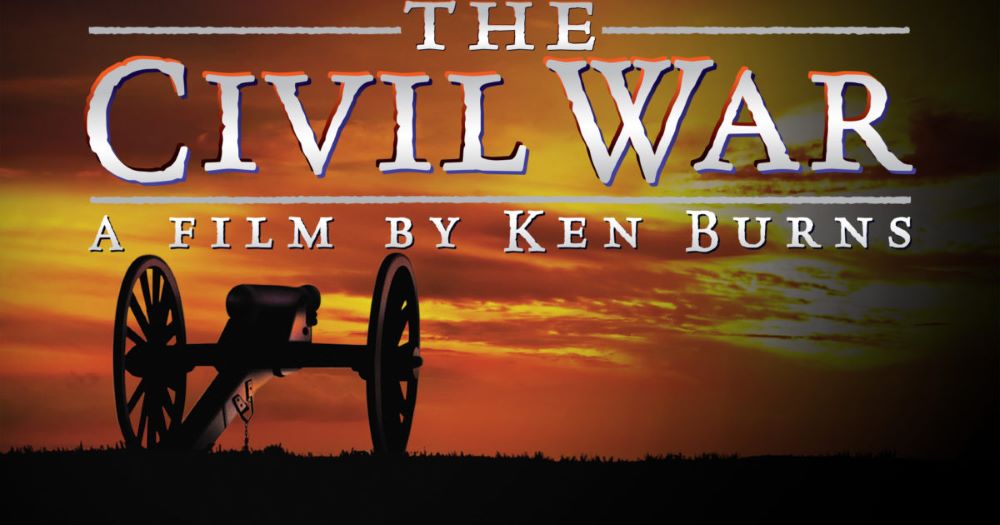

Ken Burns’ The Civil War stands as one of those rare documentaries that completely reshapes how people think about both history and the craft of documentary filmmaking. Released in 1990, it’s been over three decades since it first aired, yet it still feels monumental in its reach and emotional resonance. Instead of serving as a dry classroom recounting of battles and dates, it’s an experience that makes you feel the war’s human dimension—the people who fought it, lived through it, and were changed forever by its violence and ideals. Burns manages to take America’s bloodiest conflict and give it a pulse, telling the story not only through historians and statistics but through letters, diaries, and voices that make you feel connected to the 1860s as if it all just happened yesterday.

One of the most defining parts of The Civil War is its look and rhythm. Burns’ now-famous visual style—those slow pans and zooms across black-and-white photographs—became such a signature technique that it’s now built into editing software as “the Ken Burns effect.” It might sound simple, but the way he moves those still images feels like breathing life into ghosts. Every slow zoom on a soldier’s uncertain face, every fade over an empty battlefield, has meaning. Before Burns, most historical documentaries presented facts through re-enactments or stiff academic interviews. Burns dared to make photographs speak on their own. The pacing he uses is hypnotic—deliberate, unwavering, and emotionally tuned to each shot. It’s a visual rhythm that invites reflection instead of speed. The whole thing feels like time itself has slowed down so history can whisper its fullest story.

The narration, provided by David McCullough, ties the sprawling story together with a sense of calm authority. His voice is warm, measured, and almost timeless, acting less like a narrator and more like an old friend who knows the past intimately but never overstates it. McCullough’s presence builds trust—no hype, no theatrics, just thoughtful storytelling. Burns pairs that voice with readings from letters, diaries, and contemporary accounts, delivered by a lineup of talented voice actors like Jason Robards, Sam Waterston, and Morgan Freeman. Their readings never feel like performances; they feel lived in, restrained, and sincere. This combination of voice and image creates a tone that is both haunting and beautiful, one that makes history feel alive but not romanticized.

A huge part of why the series feels so moving is Jay Ungar’s “Ashokan Farewell.” Oddly enough, it’s not a Civil War-era tune at all—it was written in the 1980s—but it fits so organically with the documentary’s mood that it’s impossible to think about the series without hearing it. The plaintive fiddle melody has a mournful warmth, evoking the loss and longing that defines the entire project. Burns and his team used it in just the right measure: when the music plays, it deepens emotion rather than dictating it. Combined with other period-appropriate folk songs, banjo pieces, and hymns, the soundtrack acts as the emotional current guiding the story through landscapes of death, courage, and change.

The structure of The Civil War is deceptively simple but brilliantly executed. Spanning nine episodes and over eleven hours in total, it charts the war from its earliest, uneasy beginnings in the political debates over slavery and statehood through to its catastrophic conclusion and fragile aftermath. Burns understood that history isn’t static; it’s emotional and cumulative. The early episodes almost feel optimistic—the tone of youthful bravado and national pride fills the air as both sides believe the conflict will end quickly. As the series progresses, though, the optimism curdles into fatigue, despair, and grief. By the time the war drags into its later years, the imagery, narration, and music all carry the weight of shared tragedy. You begin to see how idealism eroded into acceptance of horror. The careful pacing of each episode allows viewers to feel that arc not just intellectually but emotionally.

Among the many creative decisions Burns made, choosing to anchor the series around personal letters was perhaps the most effective. Through these letters, anonymous soldiers, wives, and family members speak across time. Their words carry more power than any historian’s commentary could. One of the most unforgettable moments comes from Union officer Sullivan Ballou’s letter to his wife, written shortly before he was killed. His words are devastating in their tenderness and resignation, summing up both love and mortality in a way that feels timeless. Burns threads similar letters throughout the series—from soldiers on both sides, from civilians caught in the middle, and from the enslaved people whose freedom hung in the balance. Their voices form the emotional backbone of the documentary, constantly reminding us that this was not just a war of strategy but a catastrophe of human consequence.

Alongside these voices, there’s a chorus of historians offering perspective and context. Shelby Foote, with his Southern drawl and gift for anecdote, became one of the documentary’s most recognizable figures. His storytelling bridges the gap between scholarship and folklore, even if some critics later accused him of romanticizing the Confederate perspective. Counterbalancing that, historian Barbara Fields provides some of the series’ most profound reflections, particularly regarding race and memory. Her insistence that the war’s legacy continues to shape American identity feels just as relevant now as it did in 1990. Their alternating viewpoints give the documentary balance—emotion on one side, intellect and conscience on the other.

Burns’ handling of tone is one of the most striking things on a rewatch. It’s both deeply romantic in its love of storytelling and brutally realistic in its depiction of suffering. It doesn’t sanitize the war, but it doesn’t exploit it either. You’re never shown battle reenactments, explosions, or gore. Instead, Burns conveys the violence and despair through letters, photos, and silence. He trusts the audience to fill in the horror. That’s uncommon in modern documentary work, where there’s often pressure to explain or dramatize everything. In The Civil War, silence becomes a storytelling device. The pauses between sentences, the long holds on a tattered flag or a battlefield grave, carry meaning. The documentary refuses to rush toward catharsis; it lingers in grief.

In today’s media landscape—where documentaries tend to move fast and fight for attention—Burns’ slower, more contemplative approach stands out. Back in 1990, it riveted viewers. An estimated 40 million people watched it on PBS, an unbelievable number for a historical series on public television. For many Americans, it became their most vivid introduction to their own national history. It made people talk about Gettysburg, Lincoln, emancipation, and the moral aftermath of the war in living rooms across the country. It even sparked renewed interest in Civil War books, memorials, and battlefield preservation. Burns had tapped into something rare: a collective need to understand who Americans are by understanding what nearly destroyed them.

Even decades later, The Civil War holds up both artistically and historically. Watching it now, its moral clarity about slavery as the war’s central cause feels vital, especially in a time when debates over monuments and racial politics remain heated. Burns never let the series fall into the “states’ rights” trap that muddied so many earlier narratives. He continually foregrounded the human cost of defending or destroying the institution of slavery. Still, modern viewers might wish for even more emphasis on the experiences of Black Americans, beyond the selected diaries and Douglass excerpts. The documentary touched these stories with respect but within the limits of its early-1990s format. Later historians have expanded upon what Burns began, but his foundation remains solid.

Technically, the documentary’s aged well. Restored versions bring new clarity to the old photographs, and the audio’s crisp enough to make the letters feel freshly read. The storytelling, slow-moving as it is, rewards patience. It’s not content to skim across major events; it expects you to sit with sorrow, fatigue, and loss. Watching all eleven hours feels like reading an epic novel: it’s best done gradually, letting each episode resonate before starting the next. The cumulative effect isn’t just historical understanding—it’s emotional exhaustion tempered by awe.

The Civil War remains one of the greatest nonfiction works ever broadcast. It’s not simply about battles or leaders but about the psychology of a country divided by ideals and identity. It asks questions rather than delivering verdicts—questions about sacrifice, belief, morality, and what it means to be American. Few documentaries manage to tell old stories in ways that still feel alive, but Burns achieved that through patience, empathy, and an unshakable faith in the power of storytelling. Even now, it’s hard to watch without feeling the echo of those voices—some hopeful, some broken—that seem to reach out from still photographs and faded ink. Burns didn’t just document history; he let history speak for itself. That’s why The Civil War endures.

Perhaps it’s even more important now than when it first aired. In a time when historical revisionism has begun to creep from the fringes into mainstream discourse and when the nation feels dangerously forgetful of its own moral and political lessons, Burns’ documentary serves as both a warning and a reminder. It shows what happens when ideology overtakes humanity and when a country forgets the cost of its own divisions. Watching The Civil War today feels less like revisiting the past and more like confronting the present—proof that the ghosts of that conflict remain, quietly urging us not to repeat what we once swore to never forget.