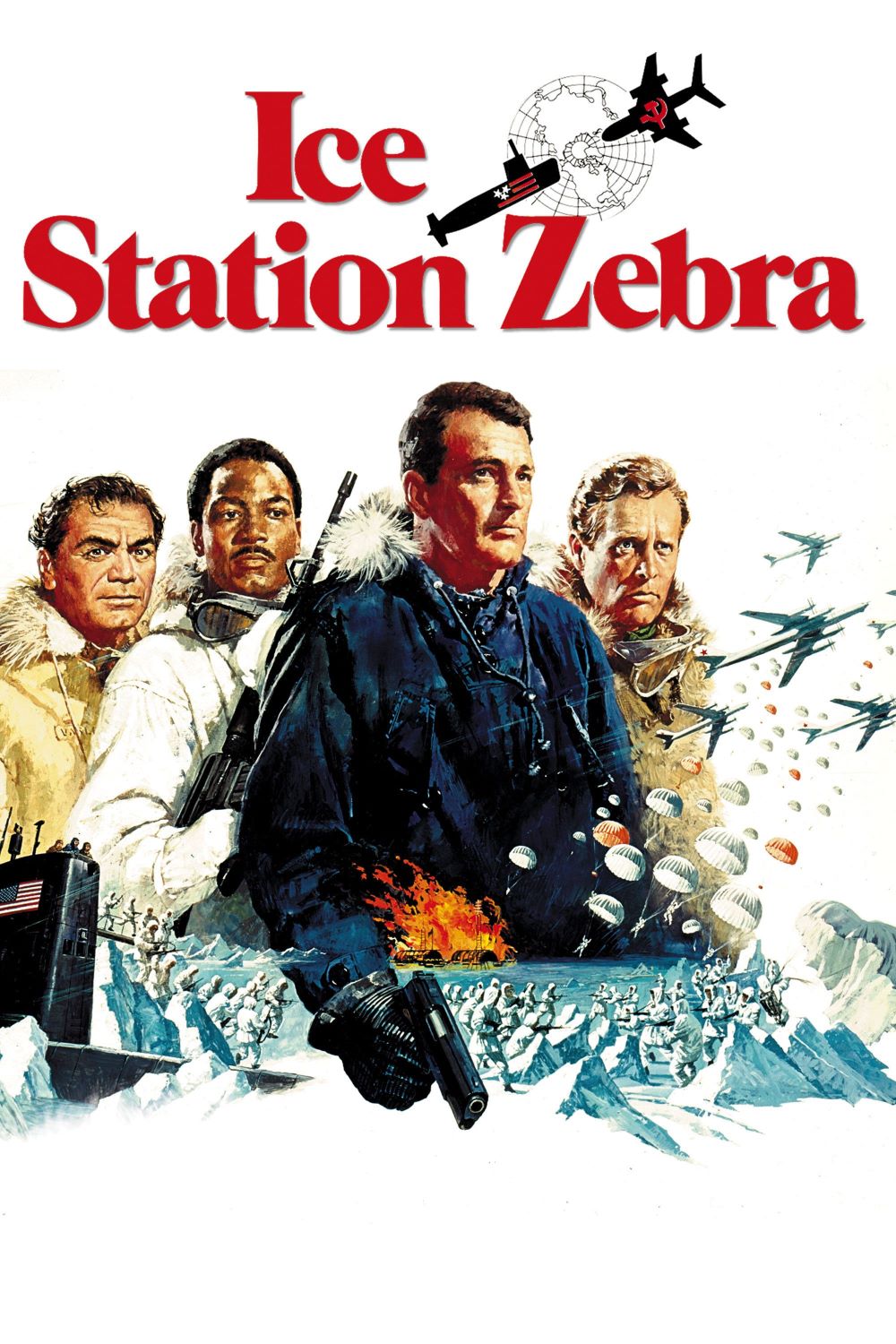

Ice Station Zebra, directed by John Sturges in 1968, slides into guilty pleasure territory like a submarine slipping under polar ice—full of big Cold War ambitions, shadowy spy games, and submarine peril that tease something epic, but so loaded with pacing hiccups, studio shortcuts, and earnest overreach that it ends up a lopsided, lovably messy ride. Sturges had already cemented his rep with crowd-roaring hits like The Magnificent Seven, where a ragtag posse of gunslingers delivered razor-sharp tension and quotable showdowns, or The Great Escape, a WWII breakout yarn crackling with clever schemes, sweaty escapes, and Steve McQueen’s motorcycle glory. Those films moved like a well-oiled engine, every scene stacking stakes and character beats into unforgettable momentum. By contrast, Ice Station Zebra feels like Sturges chasing that same high-wire ensemble vibe—a U.S. nuclear sub, the USS Tigerfish, barreling toward a trashed Arctic outpost—but bloating into a 148-minute sprawl that swaps tight plotting for endless red-lit corridor glares and withheld mission secrets. It’s not in the same league as his earlier triumphs, lacking their propulsive drive and lived-in grit, yet that very shortfall turns it into quirky comfort viewing for fans who dig flawed ’60s spectacle.

The setup hooks you quick: Commander James Ferraday, Rock Hudson’s square-jawed everyman at the helm, gets tapped for a hush-hush run to Ice Station Zebra after a satellite supposedly carrying spy photos crashes nearby. No full briefing for him, just orders to play it cool while three mystery passengers board—Mr. Jones, a buttoned-up British agent with evasive smirks; Boris Vaslov, Ernest Borgnine’s barrel-chested Russian turncoat oozing fake bonhomie; and Captain Anders, Jim Brown’s steely Marine barking orders over a squad of jarheads. As the Tigerfish dives under thickening ice floes, the sub’s innards come alive with flickering sonar pings, steam-hissing valves, and crewmen hunched over gauges in perpetual sweat. It’s claustrophobic gold at first, the hull creaking like it’s got a bad case of frostbite, echoing the trapped dread Sturges nailed in his POW camp classic but without the same spark of rebellion. Then sabotage strikes—a flooded missile bay, a wild plunge toward crush depth—and fingers start pointing. Who tampered with the ballast? Jones with his locked trunk of gadgets? Vaslov’s too-friendly vodka toasts? The Marines itching for a fight? The scene builds real sweat, divers suiting up in the nick of time, but Sturges lets the fallout drag, turning interrogation into a tea party of suspicions rather than the cutthroat blame game his best films thrived on.

These early stumbles set the tone for a film that’s promising yet perpetually off-kilter, far from the seamless revenge rhythm of The Magnificent Seven‘s dusty trails. Production fingerprints show everywhere: rumors swirl of Navy brass forcing script tweaks to glorify their boats, last-minute casting shifts from bigger names to Hudson, and a roadshow rollout with overture, intermission, and 70mm pomp that screams overambition. The Arctic plunge delivers tense highlights—the sub ramming upward through ice chunks like a whale breaching, sparks flying from shorted panels, crew barking damage reports—but lulls follow with tech jargon dumps and characters circling motives without committing to conflict. Hudson anchors it all with unflappable poise, barking commands like a TV dad in a crisis, but he lacks McQueen’s sly charisma or Yul Brynner’s brooding fire. Borgnine hams it up as Vaslov, his accent flipping from gravelly growl to vaudeville schtick during mess-hall ribbing, while McGoohan brings the sharpest edge as Jones, his dry barbs hinting at deeper layers. Brown’s Anders gets muscle but little nuance, leading a Marine crew that feels like stock tough guys waiting for their cue.

Pushing topside, the flaws bloom into full charm. The ice cap arrival unfolds in sweeping widescreen vistas—endless white expanses, howling gales whipping snow devils—but close-quarters betray the soundstage: actors plodding through “blizzards” in lightweight jackets, no puffing breath in the deep freeze, sets that wobble if you squint. It’s the kind of earnest cheesiness that sinks modern blockbusters but endears this relic, especially when the station siege erupts. Soviets drop from the sky in parachutes like deadly snowflakes, scouring the charred ruins for a buried film capsule packed with NATO missile coords. Americans fan out in white camo, trading potshots amid smoke grenades and collapsing tunnels, loyalties cracking as Vaslov’s true colors flash. Ferraday’s cool bluff seals a three-way stalemate, denying everyone the prize in a nod to mutually assured secrets. Michel Legrand’s score surges here, horns blaring over the chaos like a war drum, giving Sturges’ action chops a late workout. Yet even this payoff sprawls, talky standoffs eating screen time where his peak films would’ve sprinted to the finish.

What seals Ice Station Zebra‘s guilty pleasure status is embracing its dated quirks as features, not bugs—hammy all-male bravado, Cold War jitters turned quaint, plot gaps you could park a destroyer in. Sturges conjures submerged panic and frosty fireworks that nod to his glory days, the sub’s practical effects holding up better than some CGI today, but without the narrative steel of The Great Escape‘s tunnel triumphs or The Magnificent Seven‘s mythic standoffs, it coasts on atmosphere over precision. Clocking 148 minutes, it tests patience with filler like extended sail sequences and coy reveals, yet rewards surrender: grin at Borgnine’s bear hugs masking menace, chuckle at the Navy polish glossing gritty potential, savor the sheer balls of staging Arctic Armageddon on a backlot. Howard Hughes reportedly looped it endlessly in his casino screening rooms, and you get why—it’s hypnotic in its wonkiness, a time capsule of late-’60s Hollywood flexing before New Wave grit crashed the party.

Pop this on a stormy night with cocoa and zero expectations, and Ice Station Zebra shines as cozy flawed fun. Sturges’ touch keeps the chills coming amid the clunkers, delivering submarine squeezes, betrayals under the aurora, and a finale with enough brinkmanship bang to forgive the bloat. It’s no peer to his earlier masterpieces, more a quirky footnote, but that’s the hook: imperfect promise wrapped in icy spectacle, begging a rewatch to spot every goofy grace note. For ’60s thriller buffs, submarine nuts, or anyone needing a break from slick reboots, it’s a frosty, flawed feast worth the dive.

Previous Guilty Pleasures

- Half-Baked

- Save The Last Dance

- Every Rose Has Its Thorns

- The Jeremy Kyle Show

- Invasion USA

- The Golden Child

- Final Destination 2

- Paparazzi

- The Principal

- The Substitute

- Terror In The Family

- Pandorum

- Lambada

- Fear

- Cocktail

- Keep Off The Grass

- Girls, Girls, Girls

- Class

- Tart

- King Kong vs. Godzilla

- Hawk the Slayer

- Battle Beyond the Stars

- Meridian

- Walk of Shame

- From Justin To Kelly

- Project Greenlight

- Sex Decoy: Love Stings

- Swimfan

- On the Line

- Wolfen

- Hail Caesar!

- It’s So Cold In The D

- In the Mix

- Healed By Grace

- Valley of the Dolls

- The Legend of Billie Jean

- Death Wish

- Shipping Wars

- Ghost Whisperer

- Parking Wars

- The Dead Are After Me

- Harper’s Island

- The Resurrection of Gavin Stone

- Paranormal State

- Utopia

- Bar Rescue

- The Powers of Matthew Star

- Spiker

- Heavenly Bodies

- Maid in Manhattan

- Rage and Honor

- Saved By The Bell 3. 21 “No Hope With Dope”

- Happy Gilmore

- Solarbabies

- The Dawn of Correction

- Once You Understand

- The Voyeurs

- Robot Jox

- Teen Wolf

- The Running Man

- Double Dragon

- Backtrack

- Julie and Jack

- Karate Warrior

- Invaders From Mars

- Cloverfield

- Aerobicide

- Blood Harvest

- Shocking Dark

- Face The Truth

- Submerged

- The Canyons

- Days of Thunder

- Van Helsing

- The Night Comes for Us

- Code of Silence

- Captain Ron

- Armageddon

- Kate’s Secret

- Point Break

- The Replacements

- The Shadow

- Meteor

- Last Action Hero

- Attack of the Killer Tomatoes

- The Horror at 37,000 Feet

- The ‘Burbs

- Lifeforce

- Highschool of the Dead