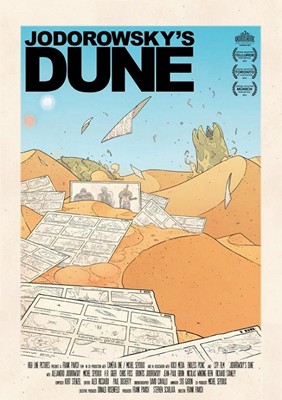

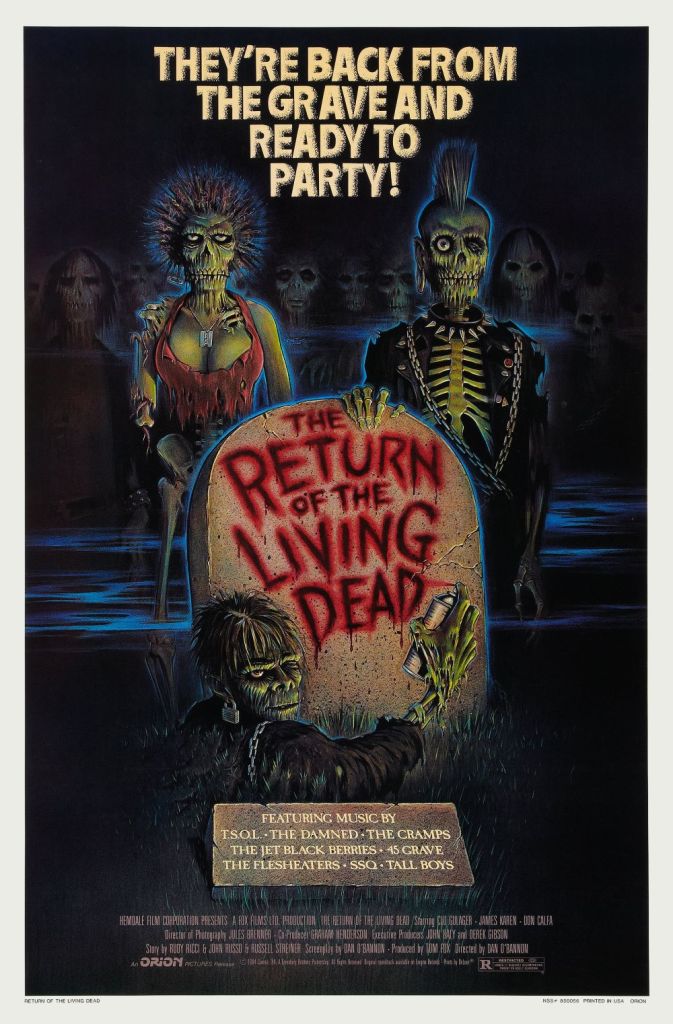

Subverting the Zombie Canon: Satire, Genre-Bending, and Decay in the Return of the Living Dead Series

When talking about cult horror films, the Return of the Living Dead series holds a special place—not only as a spin-off from George A. Romero’s seminal Night of the Living Dead, but as a unique creative force in its own right. Thanks to a legal split between Romero and co-writer John Russo over rights to the “Living Dead” name, Russo and director Dan O’Bannon got to imagine a parallel zombie universe. This franchise quickly carved out its own identity, mixing horror, black comedy, and punk spirit in a way that both paid tribute to and upended zombie tropes.

Reinventing Zombie Lore with a Wink

The original Return of the Living Dead (1985) starts with a clever “what if” twist: what if Romero’s Night wasn’t just a movie, but a dramatized cover-up of a real government disaster? This meta idea instantly frames the film as self-referential and playful, setting a tone unlike anything out at the time.

Central to the film’s identity is the invention of 2-4-5 Trioxin, a fictional military chemical designed to clear marijuana crops which instead raises the dead—zombies with surprising new abilities. Unlike the slow, drooling zombies Romero popularized, these ghouls sprint, talk, and set traps. Their hunger is peculiar as well: they crave brains exclusively, as it eases the pain of being undead. And the old rules of zombie combat? Forget shooting them in the head. These zombies resist it, raising the stakes and scare factor.

This refreshing rewrite of zombie rules allowed the movie to be both frightening and fun. The zombies were smart but still monstrous, turning classic horror expectations on their head in a way that invited both laughter and fear—a tricky balance that few horror comedies manage.

Playing with Comedy, Panic, and Punk Rock

One of the greatest strengths of the original film is how it embraces horror-comedy so naturally. It doesn’t shy away from being funny while still delivering tension. James Karen and Thom Mathews excel as the main pair—Karen’s frantic, over-the-top panicked man paired with Mathews’ straight, slowly succumbing counterpart create a perfect comedic rhythm. Their slow transformation into zombies adds a tragic dimension to what could have been simple slapstick. Meanwhile, Don Calfa’s mortician character and Clu Gulager’s warehouse owner provide a grounded center amidst chaos.

The punk subculture flavor adds another unique texture. Linnea Quigley’s famous graveyard striptease encapsulates the 1980s’ blend of irreverence, sexuality, and horror obsession. The scene is shocking, hilarious, and iconic—one of those moments that encapsulates everything this film is about: having fun with taboos while not losing the darker undercurrents of mortality and decay.

Beyond laughs, there’s biting satire here. The film skewers the government and military’s hubris—scientists create a superweapon they can’t control, leading to chaos and destruction. This reflects 1980s American anxieties about bioweapons, government cover-ups, and nuclear fears. Horror and comedy collide to reflect cultural distrust and paranoia.

The Problem of the Sequel: Part II’s Familiar Ground

When Return of the Living Dead Part II came out in 1988, it felt like the franchise was stuck in a loop. With much of the original cast returning in near-identical roles, and lines and situations seemingly recycled, the film circles back to the same story. This self-copying invites a mix of amusement and disappointment: it seems the filmmakers didn’t believe they could improve on the original and decided to replicate it instead.

While it has its moments—good practical effects and a rollicking tone reminiscent of the first film—it leans harder into comedy, sometimes at the expense of the horror. The suburban setting and clearer military lockdown raise the action stakes, but the humor feels broader and less sharp, which can make the movie seem a bit cartoonish.

In a way, Part II comments on the pitfalls of horror franchises: once you’ve struck gold with an unexpected idea, sequels often struggle to regain that freshness. This installment is entertaining, but signals the beginning of the franchise’s creative plateau.

Much Darker Territory: Part III’s Horror and Romance

With Return of the Living Dead 3 in 1993, things take a major tonal shift. Brian Yuzna’s direction removes much of the comedy and replaces it with body horror, gore, and a genuinely tragic romance. The story centers on Curt and Julie, two teenagers tragically pulled into the military’s secret zombie experiments. After Julie is accidentally killed and resurrected, she becomes a zombie who feeds on brains but manages her hunger through extreme self-inflicted pain.

This grim take pushes the franchise into more serious, intense horror territory, with heavy themes of love, loss, and bodily autonomy threaded throughout. Julie’s tortured transformation is both tragic and unsettling, symbolizing not only the loss of life but also the torment of trying to hold onto humanity while losing it from within.

Yuzna’s effects are grisly in the finest tradition of ‘90s practical SFX. The film revives the franchise’s sense of danger and stakes by mixing romance with horror, delivering something emotionally resonant and viscerally impactful. While it diverges sharply from the earlier comedic tone, Part III proves the series’ flexibility and capacity for reinvention.

Creative Collapse: Parts IV and V’s Direct-to-Cable Downfall

Sadly, the wheels come off with Return of the Living Dead 4: Necropolis and 5: Rave to the Grave, both made in 2005 and directed by Ellory Elkayem. Shot back-to-back and released direct-to-cable, these films are pale shadows of the earlier entries.

They ditch the original’s clever mix of horror and humor entirely. Instead, we get generic corporate conspiracies, confusing Eastern European settings, weak scripts, and inconsistent zombie characterizations. The zombies lose their unique “brains only” horror and instead act like run-of-the-mill undead. Even the acting is amateurish, with only Peter Coyote standing out briefly as a sinister scientist.

Part 5 further muddies continuity by introducing Trioxin as a rave drug, leading to a chaotic rave/zombie apocalypse scenario that is both baffling and poorly paced. The low-budget effects and uneven pacing betray the exhaustion and lack of passion behind these entries.

These final two films underscore a common fate for franchises that outlive their creative spark—once inventive mythology becomes shallow cliché, and attempts to cash in feel uninspired. Instead of honoring their roots, they become muddled and forgettable.

Why the Series Matters

Despite its uneven legacy, Return of the Living Dead remains important for what it dared to do in horror cinema. The first film’s originality influenced countless horror comedies and redefined how zombies could be portrayed. Its self-awareness and invention paved the way for postmodern horror, where genre is as much about commentary as it is fear.

The third film’s daring shift to tragic body horror further demonstrated the potential for zombie films to explore complex emotional and societal themes beyond gore or giggles.

While the later sequels falter, their failure serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of diluting distinct voices and creative risks in franchise filmmaking.

Ultimately, Return of the Living Dead survives in cultural memory as a zombie series that captured the spirit of its time—punk rebellion, Cold War paranoia, and genre self-mockery—with flashes of brilliance that continue to entertain and inspire.

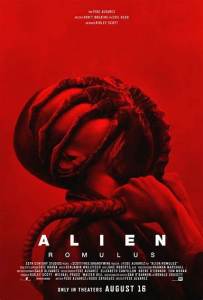

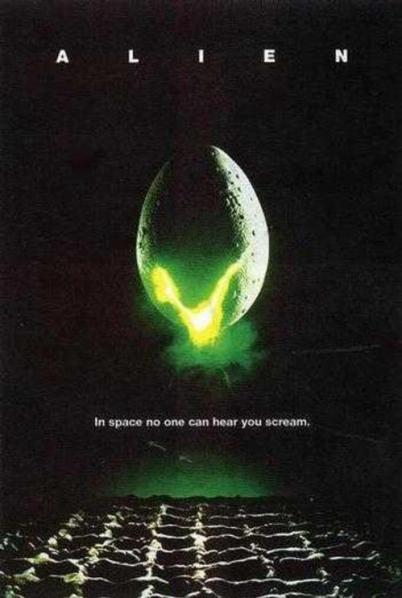

Today is 4.26, also known as “Alien Day”, and named after the planet in James Cameron’s Aliens (LV-426 / Acheron). It’s a celebration of the entire Alien Franchise, but I’m only focused on the first film as I finally saw it in the theatre in 2017.

Today is 4.26, also known as “Alien Day”, and named after the planet in James Cameron’s Aliens (LV-426 / Acheron). It’s a celebration of the entire Alien Franchise, but I’m only focused on the first film as I finally saw it in the theatre in 2017.

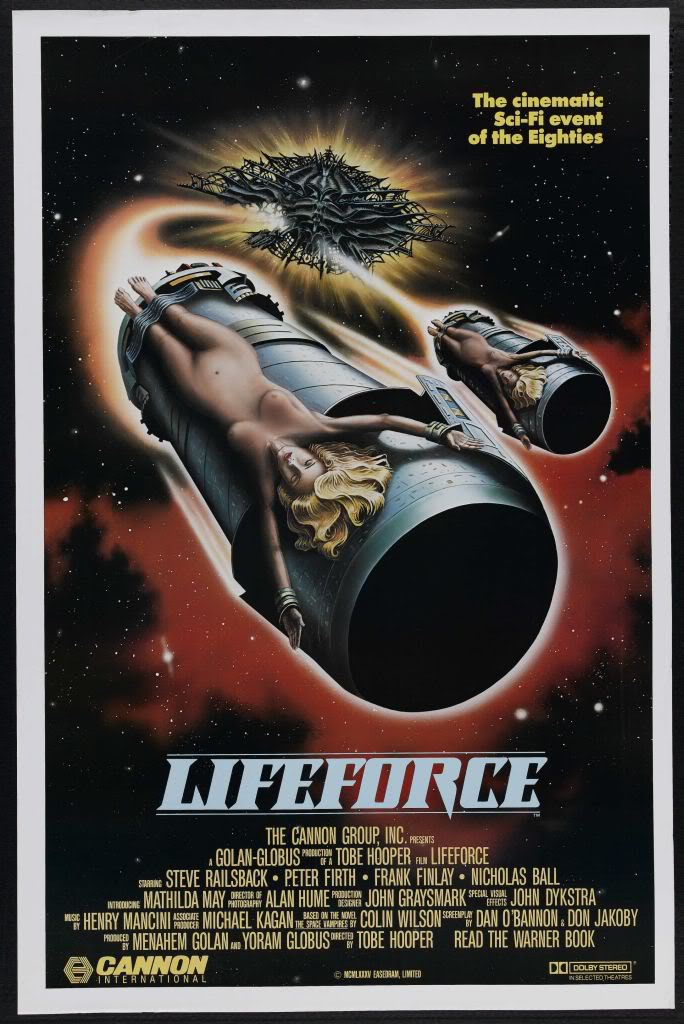

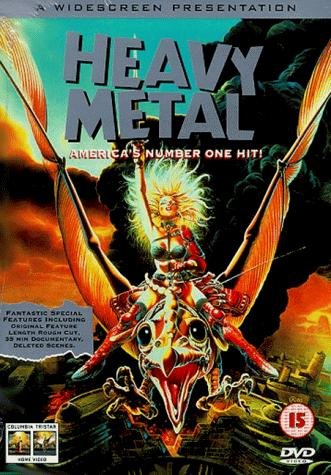

I think I was twelve when I first saw Heavy Metal. It came on HBO one night and I loved it. So did all of my friends. Can you blame us? It had everything that a twelve year-old boy (especially a 12 year-old boy who was more than a little on the nerdy side) could want out of a movie: boobs, loud music, and sci-fi violence. It was a tour of our secret fantasies. The fact that it was animated made it all the better. Animated films were not supposed to feature stuff like this. When my friends and I watched Heavy Metal, we felt like we were getting away with something.

I think I was twelve when I first saw Heavy Metal. It came on HBO one night and I loved it. So did all of my friends. Can you blame us? It had everything that a twelve year-old boy (especially a 12 year-old boy who was more than a little on the nerdy side) could want out of a movie: boobs, loud music, and sci-fi violence. It was a tour of our secret fantasies. The fact that it was animated made it all the better. Animated films were not supposed to feature stuff like this. When my friends and I watched Heavy Metal, we felt like we were getting away with something. Den (directed by Jack Stokes, written by Richard Corben)

Den (directed by Jack Stokes, written by Richard Corben) On a space station orbiting the Earth, Captain Lincoln F. Sternn is on trail for a countless number of offenses. Though guilty, Captain Sternn expects to be acquitted because he has bribed the prosecution’s star witness, Hanover Fiste. However, Hanover is holding the Loc-Nar in his hand and it causes him to tell the truth about Captain Sternn and eventually turn into a bloodthirsty giant. Captain Sternn saves the day by tricking Hanover into getting sucked out of an air lock.

On a space station orbiting the Earth, Captain Lincoln F. Sternn is on trail for a countless number of offenses. Though guilty, Captain Sternn expects to be acquitted because he has bribed the prosecution’s star witness, Hanover Fiste. However, Hanover is holding the Loc-Nar in his hand and it causes him to tell the truth about Captain Sternn and eventually turn into a bloodthirsty giant. Captain Sternn saves the day by tricking Hanover into getting sucked out of an air lock. In the film’s final and most famous segment, Taarna, the blond warrior was featured on Heavy Metal‘s poster, rides a pterodactyl across a volcanic planet, killing barbarians, and finally confronting the Loc-Nar. She sacrifices herself to defeat the Loc-Nar but no worries! We return to Earth where, for some reason, the Loc-Nar explodes and the girl from the beginning of the film is revealed to be Taarna reborn. She even gets to fly away on her pterodactyl. Taarna was really great when I was twelve but today, it is impossible to watch it without flashing back to the Major Boobage episode of South Park.

In the film’s final and most famous segment, Taarna, the blond warrior was featured on Heavy Metal‘s poster, rides a pterodactyl across a volcanic planet, killing barbarians, and finally confronting the Loc-Nar. She sacrifices herself to defeat the Loc-Nar but no worries! We return to Earth where, for some reason, the Loc-Nar explodes and the girl from the beginning of the film is revealed to be Taarna reborn. She even gets to fly away on her pterodactyl. Taarna was really great when I was twelve but today, it is impossible to watch it without flashing back to the Major Boobage episode of South Park.