The Death Merchant series by Joseph Rosenberger is a loud, relentless block of pulp action that feels less like a set of tidy thrillers and more like being dropped into a never-ending firefight powered by paranoia, gore, and fringe theorizing. It is the kind of series where your tolerance for over-the-top violence and unfiltered ideology will decide almost immediately whether you keep going or tap out after a book or two.

At the center of it all is Richard Camellion, the so-called Death Merchant: a master of disguise, martial arts, and “wet work” who usually contracts with off-the-books branches of Western intelligence for the jobs that are too dirty or politically dangerous to be handled in daylight. He is pitched as “a man without a face,” a professional who drifts from mission to mission, changing identities as easily as he swaps weapons, and charging serious money for operations that will leave plenty of bodies on the ground. Over the life of the series, he goes from taking on organized crime in the States to fighting terrorists, neo-Nazis, rogue generals, occult cults, and even plots involving aliens and lost civilizations. The world these books build is an anything-goes playground where paramilitary raids, Cold War spy games, and bizarre pseudo-science exist side by side, held together less by realism and more by sheer velocity and an obsession with tactics, gear, and mayhem.

Camellion, as a character, is deliberately underdeveloped in the conventional sense. There are fragments of backstory—St. Louis roots, an engineering degree, a Texas ranch with pet pigs, hints that he once taught history—but these details feel more like flavor text than emotional anchors. His real personality is defined by efficiency and detachment. He doesn’t agonize over moral lines; the mission objective comes first, and if that means innocent people or even cops get killed, so be it. The series is notably more nihilistic than many of its men’s-adventure peers, going so far as to show Camellion and his team gunning down large numbers of police officers when they get in the way of a job. There are gestures toward a personal code—he donates part of his fees to struggling students and the underprivileged in Texas—but that philanthropic angle never softens the basic reality that you’re dealing with a protagonist who treats lethal force as a casual tool rather than a last resort.

The real appeal, at least for fans, lies in the way Rosenberger stages and describes action. The violence is intensely graphic and highly technical, full of precise talk about trajectories, calibers, anatomy, and battlefield tactics. Shootouts and raids are broken down moment by moment, like a cross between a field manual and splatter prose, and they tend to go on long enough that you either settle into the rhythm or start to feel like you’re stuck in an endless report. Between all the bullets and explosions, the books frequently pause for gear talk—special gadgets, exotic weapons, improvised tech—and this side of the series is surprisingly imaginative, from microwave jammers to bizarre field devices that wouldn’t look out of place in a low-budget spy movie. When the stories drift into science-fiction or occult territory, that same almost deadpan, “here’s how it works” tone is applied to alien relics, psionic warfare, or secret cities, which only adds to the series’ strange charm.

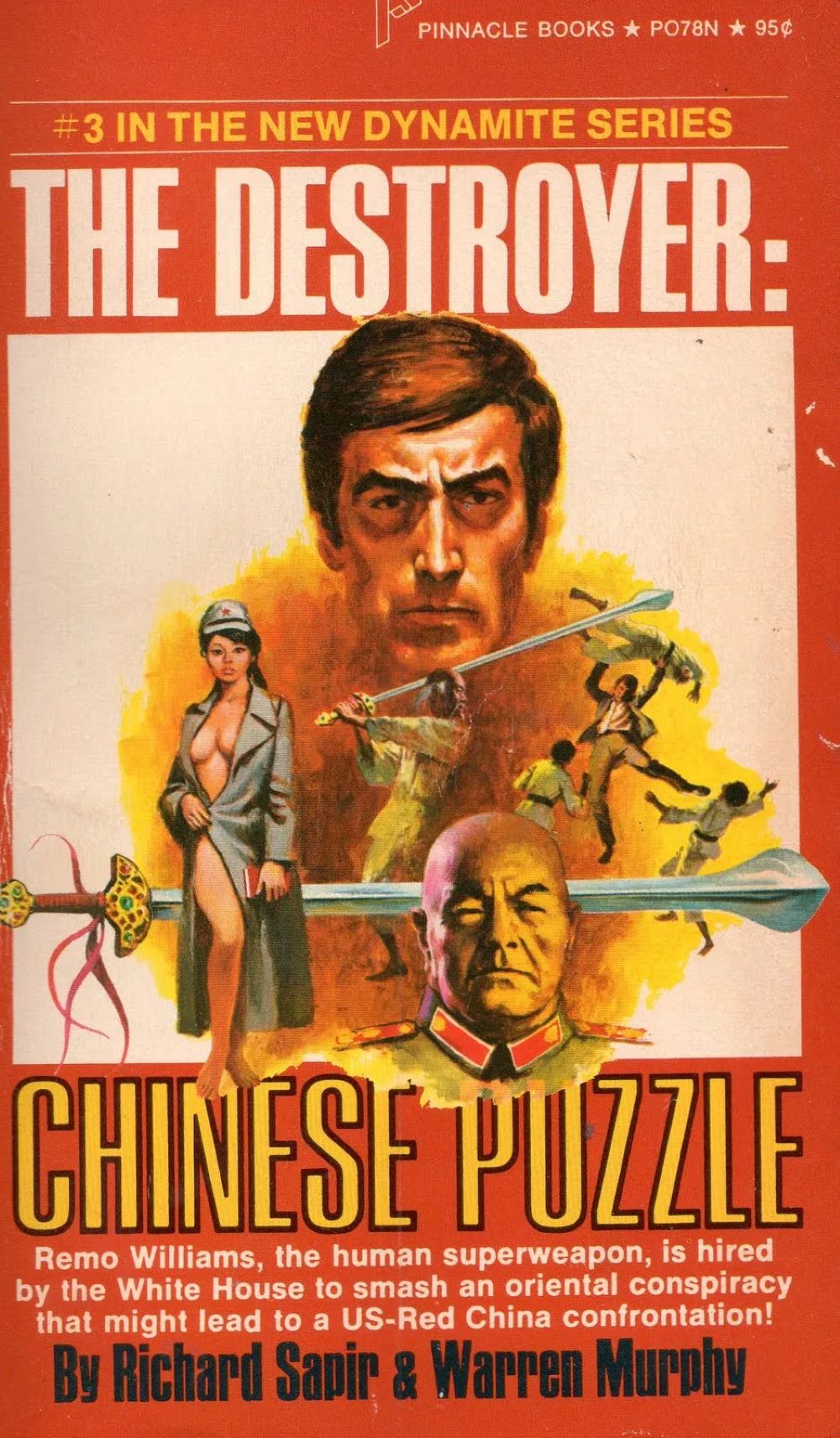

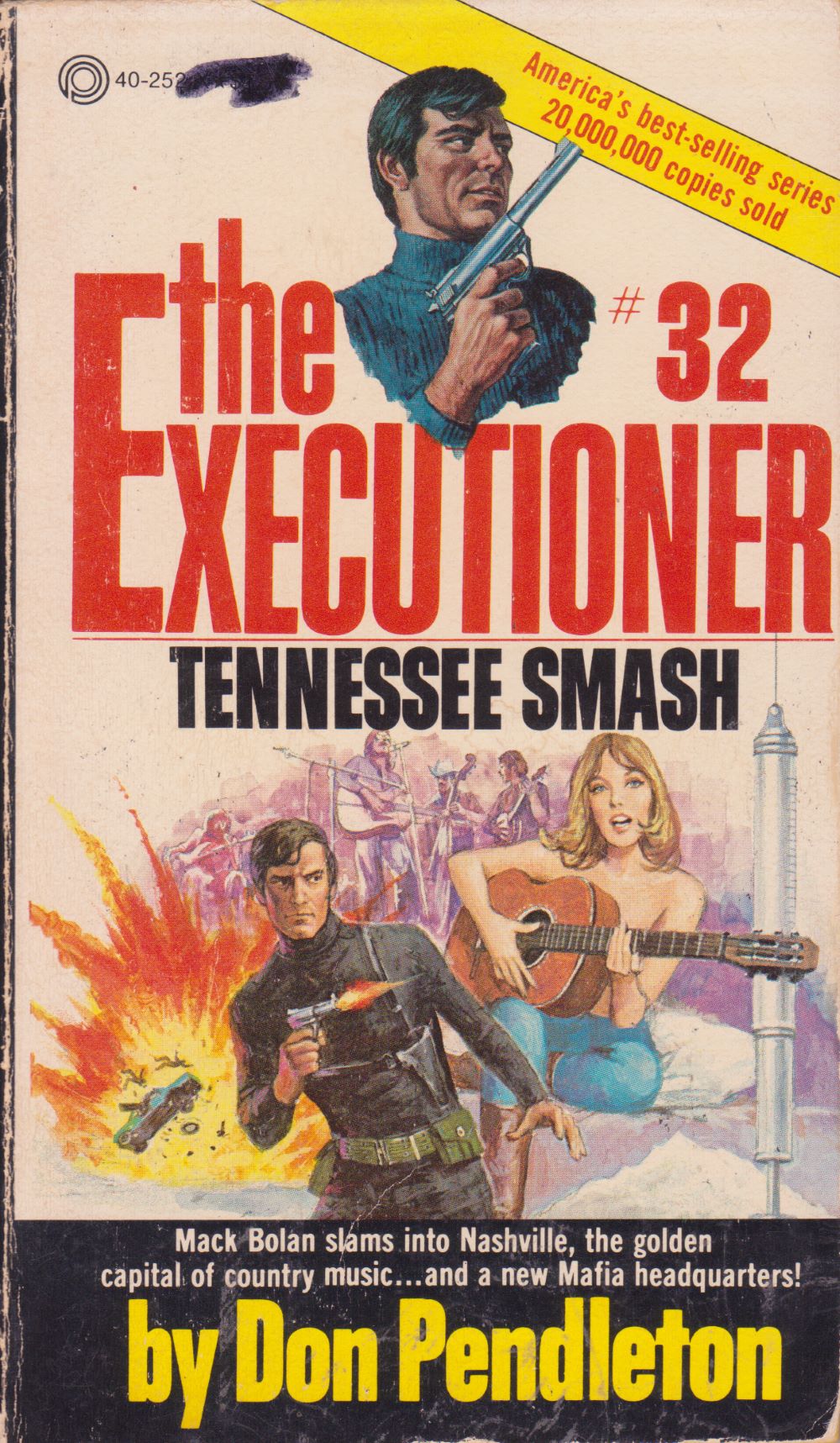

Set against the broader landscape of 1970s–80s men’s adventure fiction, The Death Merchant both fits and mutates the template. It shares the basic chassis with series like The Executioner and The Destroyer: a super-competent operative, a paperback-per-mission structure, high body counts, and a constant churn of global crises. Where Mack Bolan’s saga leans on revenge, wounded honor, and a tangible sense of moral outrage, Camellion’s world is colder and more openly cynical; the emotional framing is thinner, and the books care much more about how an op is executed than about the psychological fallout. Compared to Remo Williams and his mentors in The Destroyer, the difference is tone. The Destroyer often treats its excesses with a wink, using satire and self-awareness to keep the carnage oddly light on its feet, while The Death Merchant plays things straight, even when plots involve cloning the hero, stumbling across Atlantean technology, or battling cults armed with mind-control drugs. In that sense, Rosenberger’s series feels like the genre with the safety off—less polished, less accessible, but also more unapologetic in how far it will chase its own wild ideas.

None of this would be quite so jarring if the worldview baked into the books weren’t as sharp-edged as it is. The series openly reflects the prejudices and anxieties of its time, and not in a subtle way: racism, sexism, and class hostility are frequent, along with a deep suspicion of almost everyone outside the protagonist’s narrow circle. Long digressions into politics, conspiracy theories, and metaphysics often read like the author stepping onto a soapbox, turning scenes into lectures that can be fascinating, infuriating, or simply exhausting depending on your mood. That ideological intensity, combined with the clinical violence and the lack of real emotional counterweight, makes the series a tough sell for readers looking for nuance or heroism in the more traditional sense. At the same time, it is exactly what gives these books their unmistakable flavor and helps explain why they’ve developed a cult following rather than vanishing completely into the used-book bins.

Taken together, The Death Merchant novels are wildly uneven, sometimes ridiculous, and frequently offensive, but they are also distinct and weirdly committed to their own warped vision of men’s adventure fiction. If you approach them as straightforward thrillers with the usual expectations of character arcs and tidy plotting, they will almost certainly disappoint. If you come to them as artifacts from the outer fringes of pulp—paperbacks that push violence, ideology, and high-concept plotting further than their more famous shelfmates—they become a fascinating, if abrasive, deep dive into what this genre looks like when nothing is toned down. For readers who like their action fiction loud, excessive, and unconcerned with respectability, there is a certain grim entertainment to be had in watching Richard Camellion move from one catastrophe to the next.

Below is a list of the main series titles, which gives a good sense of the range and escalating absurdity of Camellion’s missions:

1. The Death Merchant – Richard Camellion versus the Chicago mob.

2. Operation Overkill – The demented leaders of the Knights of Vigilance plan to assassinate the President and overthrow the government.

3. The Psychotron Plot – The Russians and Egyptians team up to use a brain-scrambling device on Israel.

4. Chinese Conspiracy – The Chinese plan to maneuver a submarine into Canadian waters and shoot a US space shuttle out of the sky.

5. Satan Strike – The CIA and GRU combine forces to stop a dictator of a Caribbean nation from using a potent and deadly super-virus.

6. The Albanian Connection – Neo-Nazis, bent on reunifying Germany and restoring the Reich, have assembled seven nuclear bombs to use against the U.S., Europe, and Russia.

7. The Castro File – The Russians plan to gain complete control of Cuba by assassinating Castro and having a lookalike take his place.

8. The Billionaire Mission – Cleveland Winston Silvestter, a paranoid billionaire, believes he is Satan’s chosen disciple and is hellbent on triggering World War III.

9. The Laser War – A Nazi super-laser is pursued.

10. The Mainline Plot – Communists in North Korea have created a super-potent, super-addictive strain of heroin called Peacock-4. By introducing the heroin into the U.S., they hope to enslave a generation of young adults.

11. Manhattan Wipeout – The Death Merchant causes trouble for the four mob families in New York City.

12. The KGB Frame – Flash! Camellion turns double agent. The target of both his colleagues and his enemies, the Death Merchant becomes the object of the most intense manhunt in the history of international espionage.

13. The Mato Grosso Horror – Camellion leads an expedition into the Brazilian jungle to locate a group of Nazis who are perfecting a mind-control drug.

14. Vengeance of the Golden Hawk – The DM is tasked with saving Tel Aviv from a rocket barrage containing a deadly nerve gas.

15. The Iron Swastika Plot – The Nazi organization known as the Spider returns!

16. Invasion of the Clones – Camellion versus five clones of himself in Africa.

17. The Zemlya Expedition – The Death Merchant attempts to rescue a scientist from an underwater Russian city/complex in the Arctic Ocean.

18. Nightmare in Algeria – Camellion battles two terrorist organizations who have joined forces: the Black Avengers and the Blood Sons of Allah.

19. Armageddon, USA! – A far-right group threatens to set off nukes in three American cities unless its demands are met.

20. Hell in Hindu Land – The Death Merchant leads an expedition to a Buddhist monastery in India, where the bodies of aliens (and the secrets of their civilization) may be hidden.

21. The Pole Star Secret – Camellion treks to the North Pole to investigate a possible alien world hidden under the ice cap.

22. The Kondrashev Chase – A highly placed spy behind the Iron Curtain has disappeared while trying to escape to the West, and Camellion must find and rescue him.

23. The Budapest Action – The Hungarians are working with the KGB to develop a hallucinogenic toxin to be released over American cities and the DM is tasked with stopping them.

24. The Kronos Plot – Fidel Castro plans to destroy the Panama Canal.

25. The Enigma Project – Spying on Russia under the cover of finding Noah’s Ark.

26. The Mexican Hit

27. The Surinam Affair

28. Nipponese Nightmare – Japanese terrorists try to frame the CIA for murder.

29. Fatal Formula – Tracking a man-made flu strain.

30. Shambhala Strike – An ancient maze of caverns means China could easily invade.

31. Operation Thunderbolt – A bomb-maker is captured by North Korean forces.

32. Deadly Manhunt – An ally betrays Camellion.

33. Alaska Conspiracy

34. Operation Mind-Murder

35. Massacre in Rome – A civilian seems to be able to predict the future.

36. The Cosmic Reality Kill – A cult leader is targeting kids.

37. The Bermuda Triangle Action – The Russians are drilling along a fault line in the Atlantic, where a few well-placed hydrogen bombs could cause catastrophe for the U.S.

38. The Burning Blue Death – A neo-Nazi group called the Brotherhood has created a device that can make a human being spontaneously combust.

39. The Fourth Reich – A neo-Nazi conspiracy to trigger an atom bomb (twice as powerful as Hiroshima) in Cairo is crushed.

40. Blueprint Invisibility – The Red Chinese have stolen a vital top secret U.S. file dealing with electronic camouflage.

41. Shamrock Smash – Someone is supplying the IRA with weapons and the CIA and SIS call on Richard Camellion to find out who.

42. High Command Murder – At the end of World War II, American soldiers stole 100 crates of Nazi gold and hid the loot in an abandoned mine shaft in northern France. The Death Merchant races the Nazis to find it.

43. The Devil’s Trashcan – Did the Nazis bury treasure at the bottom of Lake Toplitz during World War II? Camellion, et al. plan to find out.

44. Island of the Damned – Soviet forces develop mind-reading technology.

45. The Rim of Fire Conspiracy – The Russians hope to trigger volcanoes on the U.S. West Coast by exploding bombs along fault lines.

46. Blood Bath – Camellion assists South Africa’s ruling whites defeat groups of blacks demanding an end to apartheid.

47. Operation Skyhook

48. Psionics War

49. Night of the Peacock

50. The Hellbomb Theft – Camellion must stop two mini-nukes from falling into the hands of Kaddafi, the dictator of Libya.

51. The Inca File

52. The Flight of the Phoenix

53. The Judas Scrolls

54. Apocalypse, USA! – Libyan terrorists plan to spray deadly nerve gas across the Eastern Seaboard. Not if the Death Merchant has anything to say about it!

55. Slaughter in El Salvador – The Death Merchant heads to war-torn El Salvador, where he tangles with death squads and Communist Sandinista rebels, with predictable carnage.

56. Afghanistan Crashout

57. The Romanian Operation

58. The Silicon Valley Connection

59. The Burma Probe – The Death Merchant teams up with Thunderbolt Unit Omega and Lester Vernon “The Widowmaker” Cole to stop a Chinese territory grab.

60. The Methuselah Factor

61. The Bulgarian Termination

62. The Soul Search Project – Camellion pursues a scientist who can talk to the dead. The protagonist and his allies willingly kill several dozen NYPD officers.

63. The Pakistan Mission – A Communist plan to invade Pakistan.

64. The Atlantean Horror – Camellion is in Antarctica, trying to keep an “energy converter” (buried 70,000 years ago by scientists from Atlantis) out of the hands of the Russians.

65. Mission Deadly Snow – The Death Merchant must destroy a South American drug cartel intent on supplying Fidel Castro with thousands of pounds of cocaine.

66. The Cobra Chase – Camellion tracks the Cobra, who escaped from the cocaine processing plant in the previous book.

67. Escape From Gulag Taria – A Soviet physicist who specializes in weather modification wants to defect.

68. The Hindu Trinity Caper – Camellion tracks down an East German spy who has stolen some parts to a nuclear weapon.

69. The Miracle Mission – The Shroud of Turin is stolen by an Arab terrorist group. Camellion’s job is to get it back.

70. The Greenland Mission – Camellion and his crew investigate a ‘U.F.O.’ in Greenland.

Previous Guilty Pleasures

- Half-Baked

- Save The Last Dance

- Every Rose Has Its Thorns

- The Jeremy Kyle Show

- Invasion USA

- The Golden Child

- Final Destination 2

- Paparazzi

- The Principal

- The Substitute

- Terror In The Family

- Pandorum

- Lambada

- Fear

- Cocktail

- Keep Off The Grass

- Girls, Girls, Girls

- Class

- Tart

- King Kong vs. Godzilla

- Hawk the Slayer

- Battle Beyond the Stars

- Meridian

- Walk of Shame

- From Justin To Kelly

- Project Greenlight

- Sex Decoy: Love Stings

- Swimfan

- On the Line

- Wolfen

- Hail Caesar!

- It’s So Cold In The D

- In the Mix

- Healed By Grace

- Valley of the Dolls

- The Legend of Billie Jean

- Death Wish

- Shipping Wars

- Ghost Whisperer

- Parking Wars

- The Dead Are After Me

- Harper’s Island

- The Resurrection of Gavin Stone

- Paranormal State

- Utopia

- Bar Rescue

- The Powers of Matthew Star

- Spiker

- Heavenly Bodies

- Maid in Manhattan

- Rage and Honor

- Saved By The Bell 3. 21 “No Hope With Dope”

- Happy Gilmore

- Solarbabies

- The Dawn of Correction

- Once You Understand

- The Voyeurs

- Robot Jox

- Teen Wolf

- The Running Man

- Double Dragon

- Backtrack

- Julie and Jack

- Karate Warrior

- Invaders From Mars

- Cloverfield

- Aerobicide

- Blood Harvest

- Shocking Dark

- Face The Truth

- Submerged

- The Canyons

- Days of Thunder

- Van Helsing

- The Night Comes for Us

- Code of Silence

- Captain Ron

- Armageddon

- Kate’s Secret

- Point Break

- The Replacements

- The Shadow

- Meteor

- Last Action Hero

- Attack of the Killer Tomatoes

- The Horror at 37,000 Feet

- The ‘Burbs

- Lifeforce

- Highschool of the Dead

- Ice Station Zebra

- No One Lives

- Brewster’s Millions

- Porky’s

- Revenge of the Nerds

- The Delta Force

- The Hidden

- Roller Boogie

- Raw Deal