“We are not men disguised as dogs. We are wolves disguised as men.” — Hachiro Tohbe

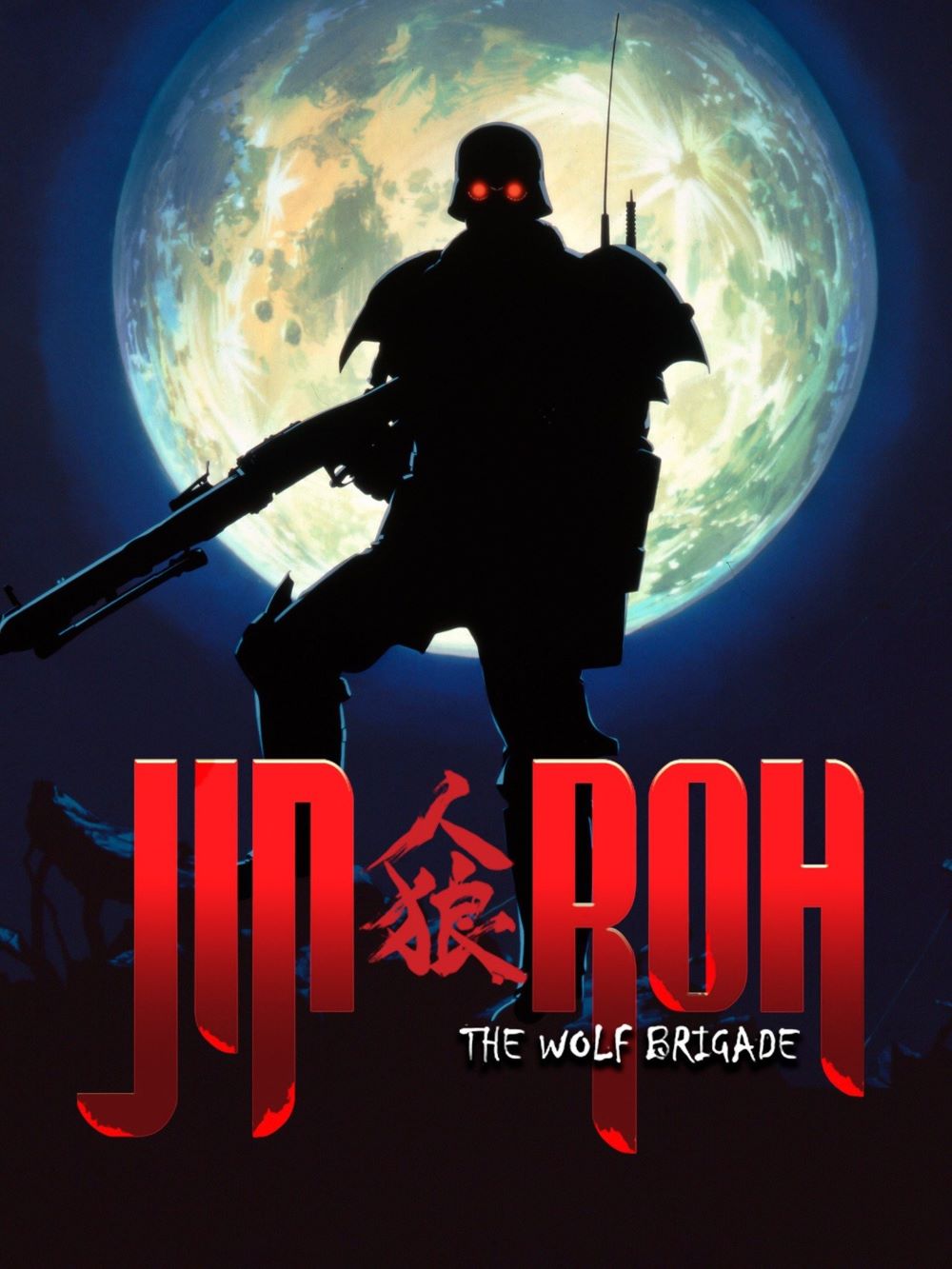

Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade stands out as a gripping 1999 anime film that blends political intrigue, psychological depth, and haunting visuals into something truly unforgettable. Directed by Hiroyuki Okiura with a screenplay by Mamoru Oshii, it drops you into an alternate post-WWII Japan where the Allies lost, Nazi influence lingers, and society teeters on chaos from endless terrorist attacks and brutal crackdowns. This isn’t your typical high-octane anime romp; it’s a slow-burn character study wrapped in a thriller that forces you to confront the monsters we become in times of fear and division, making it an absolute must-watch for anyone craving mature storytelling in animation.

Right from the opening scenes, the film hooks you with its oppressive atmosphere. We meet Kazuki Fuse, a stoic member of the Kerberos Panzer Cop (KPC), an elite anti-terror unit decked out in powered exoskeletons called Protect Gear that make them look like armored wolves prowling the streets. Fuse chases a young female terrorist from the far-left Sect group into the sewers. She’s just a scared girl clutching a bomb, and when he has her dead to rights, he hesitates—can’t pull the trigger. She blows herself up instead, leaving him shell-shocked and questioning everything. That moment alone is a gut-punch, setting up Fuse’s arc as a man caught between duty and his fraying humanity. The animation captures it perfectly: shadows swallow the damp tunnels, rain-slicked streets reflect flickering neon, and every footstep in those heavy suits echoes like doom approaching.

What elevates Jin-Roh is its alternate history setup, which feels eerily plausible. Japan never got nuked or occupied by the U.S.; instead, it’s a pressure cooker of failed U.S. aid, communist uprisings, and a government unleashing paramilitary forces to keep control. The Capital Police clash with regular cops and intelligence agencies like Public Security, all vying for power amid riots and bombings. It’s not just backdrop—it’s the beating heart of the story, mirroring real-world tensions like Cold War paranoia or modern insurgencies without ever feeling preachy. Fuse gets sidelined to “re-education” after his hesitation, where he’s grilled by superiors and hauntedJin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade stands out as a gripping 1999 anime film that blends political intrigue, psychological depth, and haunting visuals into something truly unforgettable. Directed by Hiroyuki Okiura with a script from Mamoru Oshii, it crafts an alternate history where Japan never fully shakes off authoritarian shadows after a failed U.S. occupation, making it a slow-burn thriller that demands your attention from the first frame.

The story kicks off in a dystopian 1950s Tokyo gripped by unrest, where the government deploys the elite Kerberos Panzer Cops—think heavily armored stormtroopers in powered exosuits—to combat the far-left Sect, a terrorist group using young girls as human bombs. Our protagonist, Kazuki Fuse, is one of these wolfish enforcers, a guy hardened by the grind of urban warfare. Early on, he chases a teenage Sect courier, Nanami Agawa, into rain-slicked sewers. She’s got a bomb vest strapped on, and point-blank, he hesitates to pull the trigger. She blows herself up instead, leaving Fuse shell-shocked and facing a psych evaluation that sidelines him from the force.

This hesitation isn’t just a plot device; it’s the spark that ignites Fuse’s unraveling. Reassigned to retraining, he bumps into an old academy buddy, Izaki Henmi, now with Public Security, the sneaky intel arm plotting to dismantle Kerberos in favor of subtler tactics. Henmi feeds Fuse details on Nanami, stirring guilt that pulls him to her makeshift grave. There, he meets Kei Amemiya, who claims to be Nanami’s big sister. She’s soft-spoken, cooks him hearty meals like beef stew in her cramped apartment, and slowly cracks through his armored exterior. Their bond feels genuine amid the paranoia—nights reading Little Red Riding Hood, her teasing him about his wolfish instincts—but it’s laced with unease as factions clash in bloody street riots.

What elevates Jin-Roh is how it weaves the fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood into its core. Fuse embodies the wolf, disguised in human skin but driven by primal loyalties. Kei plays Red, vulnerable yet complicit, her red hood symbolizing the Sect’s cloaked threats. The film flashes back to Fuse’s dreams of this story, narrated in a chilling child’s voice, mirroring his internal war: Can a wolf become a man, or is he doomed to devour what he loves? This allegory sharpens the political knife—Kerberos as fascist wolves protecting the state, Public Security as scheming hunters, the Sect as radical prey fighting back with desperate ferocity.

Visually, it’s a knockout. Production I.G.’s animation captures a gritty, oppressive Tokyo with meticulous detail: foggy streets lit by harsh sodium lamps, the clank of Protect Gear suits echoing like mechanized doom, sewers dripping with menace. No flashy mecha battles here; action hits hard but sparse—a riot scene with cops mowing down protesters in slow-motion chaos, bullets sparking off armor. The color palette stays muted, grays and blues amplifying isolation, while intimate moments glow warmer, like candlelit dinners that hint at fragile humanity. Sound design seals it: muffled gunfire, pounding rain, a sparse score by Shigeto Saegusa that lets silence breathe tension.

Thematically, Jin-Roh doesn’t pull punches on loyalty’s cost. Fuse grapples with betrayal at every turn—Henmi’s double-dealing, Kei’s true role as a Public Security plant coerced into luring him out. Deeper still, it probes dehumanization: soldiers conditioned to kill become liabilities if empathy creeps in. The film’s climax in a foggy junkyard twists the knife—Fuse, reinstated by the shadowy Jin-Roh (a rogue Kerberos splinter), faces an impossible order. Kei recites the fairy tale’s climax, embracing him as he fires, her death echoing Red’s fate. No heroes triumph; just wolves feasting in the dark.

Pacing might test casual viewers—it’s deliberate, more mood piece than adrenaline rush, clocking 99 minutes of brooding buildup. Voice acting shines, especially Fuse’s quiet torment from Hideo Sakaki and Kei’s wistful edge from Yurika Hino. Supporting cast, like the stone-cold Kerberos captain, adds layers without stealing focus. Influences nod to Oshii’s Patlabor and Ghost in the Shell, but Okiura’s touch feels more personal, less cyberpunk flash.

So why is Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade a must-watch? First, its prescience. Released amid late-’90s stability, it nails endless cycles of terror and counterterror, loyalty tests, and institutional rot—echoes in today’s headlines that make it feel ripped from 2026 newsreels. Alternate history aside, the human core endures: hesitation as rebellion, love as trap, violence as identity. It’s “grown-up anime” that trusts you to connect dots, rivaling Akira in ambition but surpassing in emotional gut-punch.

Second, technical mastery holds up flawlessly. In an era of CGI slop and quippy spectacles, Jin-Roh‘s hand-drawn grit reminds why anime conquered global imaginations. Every frame rewards rewatches—spot the wolf motifs in shadows, the Red hoods in crowds. It’s not fan service; it’s artistry that lingers, haunting like a bad dream.

Third, it challenges easy morals. No side’s clean: Sect kids are pawns, cops brutal zealots, intel weasels manipulative. Fuse’s arc forces you to question: Is mercy weakness in a wolf’s world? Or the last spark of manhood? This ambiguity sparks debates, perfect for film buffs dissecting authoritarianism or trauma’s scars. Pair it with Patlabor 2 for the full Kerberos saga—it’s expanded universe done right, sans MCU bloat.

Critics rave for reason: 7.3/10 on IMDb, cult status among cinephiles. If you dig thrillers like Children of Men or The Lives of Others, this bridges anime and live-action prestige. Stream it on Crunchyroll or Blu-ray for that crisp transfer—worth every penny. Skip if you crave explosions; dive in if mature stories with fangs appeal.

Ultimately, Jin-Roh argues we’re all wolves under pressure, cloaked in civility until the hood slips. Fuse’s tragedy warns that in fractured states, personal redemption crumbles against systemic hunger. It’s not hopeful—ending on solemn wolf howls—but that’s its power: a mirror to our baser selves, urging vigilance. Must-watch for anyone serious about anime’s potential beyond tropes. It’ll chew you up and spit out questions that stick.