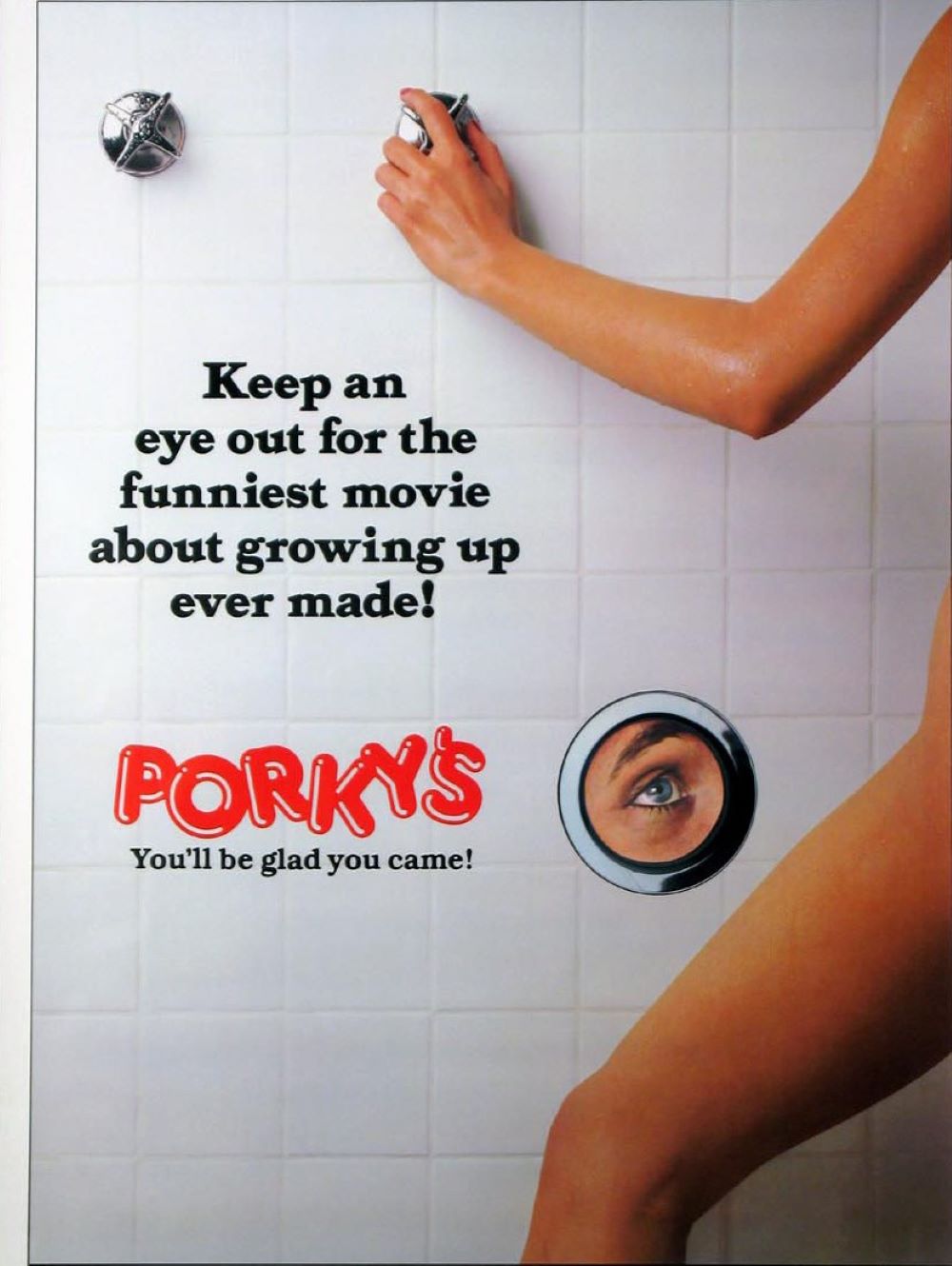

Porky’s is one of those movies that plays very differently depending on when you first see it. On the surface, it is a loud, lewd early‑’80s teen sex comedy about a bunch of high‑school boys in 1950s Florida trying to get laid and get even, but underneath the pranks and bare flesh there are streaks of surprisingly serious material about prejudice, masculinity, and power. That mix of dopey laughs and darker undercurrents is exactly what makes the film interesting to talk about, and also what makes it so divisive today.

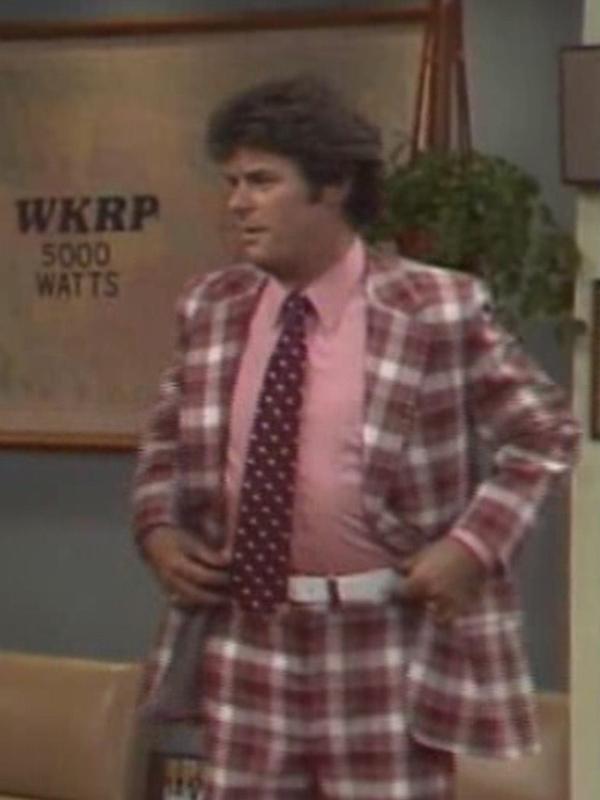

Set in the 1950s and released in 1981, Porky’s follows a tight‑knit group of teenage boys whose main goals in life are sex, sports, and practical jokes. Their adventures eventually take them to Porky’s, a sleazy backwater strip club run by the hulking, corrupt Porky, who humiliates them and sets up the revenge plot that drives the back half of the film. Around that spine, the story wanders through locker‑room banter, elaborate pranks, and various attempts to sneak into the girls’ showers or otherwise spy on naked bodies. It is very much a “horny boys on the prowl” narrative, and the film never pretends to be anything else.

What keeps it from being just another disposable sex comedy is the way some of those side stories hit harder than expected. One of the kids is brutally abused by his father, and the film doesn’t treat it like a throwaway detail; those scenes have a rawness and anger that clash with the goofy tone elsewhere. There is also a thread about anti‑Semitism and racism in their community, with one character confronting his own bigoted upbringing as he befriends a Jewish classmate and pushes back against the prejudice around him. That material is handled in a pretty straightforward, earnest way, which is jarring given how crude the surrounding humor can be, but it does show that writer‑director Bob Clark had more on his mind than dirty jokes.

The humor, for better or worse, is what most people remember. Porky’s leans heavily on slapstick and sex‑obsessed gag setups: peeping through holes in shower walls, mistaken identities during sex, ridiculous anatomical bragging, prank phone calls, and elaborate schemes that escalate into full‑on chaos. Some of the set pieces are staged with real comic timing, and if you’re on its wavelength, these sequences can still land as big, cathartic laughs. Others feel juvenile in the worst way, stretching one joke way past its breaking point, or punching down at easy targets rather than punching up at the hypocritical adults the boys are constantly butting up against.

Viewed from today’s lens, a big chunk of that humor is undeniably uncomfortable. The movie is saturated with sexist, homophobic, and racist language, and a few of the “pranks” involving the girls are essentially sexual harassment played for laughs. At the time, it was sold as a gleefully politically incorrect romp; now, those same scenes read as mean‑spirited or creepy in a way that undercuts the supposed lighthearted tone. The film occasionally tries to complicate this by giving some of the female characters sharper edges or letting them turn the tables, but it never fully escapes the fact that the camera is mostly aligned with the boys and their fantasies.

That said, Porky’s is not entirely dismissive of its women. There are moments where adult women, in particular, are allowed to call out the boys’ behavior or assert their own sexuality in ways that undercut the usual “conquest” narrative. The movie also makes a point of ridiculing hypocritical authority figures—teachers, coaches, cops, and parents—whose prudish public morals don’t match their private behavior. When Porky’s is skewering bigotry, religious hypocrisy, and small‑town moral panics, it feels sharper and more progressive than its reputation as a dumb “tits‑and‑ass” comedy suggests. Those flashes of insight are part of why some viewers argue that, beneath the sleaze, the film is quietly critical of the very attitudes it seems to indulge.

Performance‑wise, the cast is made up largely of unknowns who sell the illusion that this is a real, scrappy group of friends rather than polished Hollywood teens. The camaraderie feels genuine; their constant ribbing, in‑jokes, and shifting alliances are believable enough that you can see why the movie became a touchstone for a certain generation of viewers. Bob Clark’s direction is surprisingly controlled for such an anarchic script. He keeps the story moving, balances multiple subplots, and stages the bigger comic payoffs in a way that feels almost like a live‑action cartoon. The downside is that this slickness can make the nastier gags pop more, for better and worse.

On a technical level, Porky’s is very much a product of its time, but not a cheap one. The period detail—cars, music, clothing, diners, and dingy roadside bars—helps sell the 1950s setting, giving the film a nostalgic sheen that softens some of its rougher edges. The soundtrack leans on era‑appropriate rock and roll, which adds energy to the locker‑room and party scenes. The film also doesn’t shy away from male nudity, which was less common in comedies of the time and adds to its reputation as equal‑opportunity when it comes to what it exposes, even if the gaze is still clearly tilted toward ogling women.

Where Porky’s can stumble is in tone. The shifts between broad farce and serious drama can be abrupt. One minute you are watching a drawn‑out gag about a teacher trying to identify a student by his anatomy; the next, you are plunged into a grim confrontation with an abusive parent. That whiplash can pull you out of the movie, because the emotional weight of the dramatic scenes doesn’t always get enough breathing room before the script lurches back to naughty antics. As a result, some viewers feel the darker elements trivialize real issues, while others think those same scenes give the film more substance than its imitators.

Even if someone has never seen Porky’s, they have probably felt its influence. The film was a massive box‑office hit relative to its budget and paved the way for a wave of raunchy teen comedies through the ’80s and ’90s, eventually echoing into movies like American Pie and beyond. Its success made it clear that there was a huge audience for R‑rated, adolescent sex comedies that mixed crude jokes with a veneer of coming‑of‑age sentiment. You can see its blueprint in later films: packs of horny friends, elaborate revenge schemes, school authority figures as comic foils, and a big, raucous set piece as the payoff.

Whether Porky’s “holds up” is going to depend a lot on your tolerance for outdated attitudes and offensive language. If you go in expecting a cozy nostalgia trip, you may be surprised by how sour some jokes taste now, and how casually the film treats behavior that would be framed very differently in a modern story. If you approach it as both a time capsule and the prototype of a genre, it becomes easier to see its strengths—the lively ensemble, the willingness to poke at racism and hypocrisy, the low‑budget ingenuity in its set pieces—alongside its very real flaws.

Porky’s is neither the hidden gem some defenders make it out to be nor the irredeemable trash its harshest critics describe. It is a messy, uneven, often funny, often cringeworthy movie that captures a particular moment in pop culture, both in what it laughs at and what it takes for granted. If you are curious about the roots of modern raunchy teen comedies and prepared for the rough, politically incorrect ride, it is still worth a look as a piece of film history and as an example of how comedy ages—for better and for worse.

Previous Guilty Pleasures

- Half-Baked

- Save The Last Dance

- Every Rose Has Its Thorns

- The Jeremy Kyle Show

- Invasion USA

- The Golden Child

- Final Destination 2

- Paparazzi

- The Principal

- The Substitute

- Terror In The Family

- Pandorum

- Lambada

- Fear

- Cocktail

- Keep Off The Grass

- Girls, Girls, Girls

- Class

- Tart

- King Kong vs. Godzilla

- Hawk the Slayer

- Battle Beyond the Stars

- Meridian

- Walk of Shame

- From Justin To Kelly

- Project Greenlight

- Sex Decoy: Love Stings

- Swimfan

- On the Line

- Wolfen

- Hail Caesar!

- It’s So Cold In The D

- In the Mix

- Healed By Grace

- Valley of the Dolls

- The Legend of Billie Jean

- Death Wish

- Shipping Wars

- Ghost Whisperer

- Parking Wars

- The Dead Are After Me

- Harper’s Island

- The Resurrection of Gavin Stone

- Paranormal State

- Utopia

- Bar Rescue

- The Powers of Matthew Star

- Spiker

- Heavenly Bodies

- Maid in Manhattan

- Rage and Honor

- Saved By The Bell 3. 21 “No Hope With Dope”

- Happy Gilmore

- Solarbabies

- The Dawn of Correction

- Once You Understand

- The Voyeurs

- Robot Jox

- Teen Wolf

- The Running Man

- Double Dragon

- Backtrack

- Julie and Jack

- Karate Warrior

- Invaders From Mars

- Cloverfield

- Aerobicide

- Blood Harvest

- Shocking Dark

- Face The Truth

- Submerged

- The Canyons

- Days of Thunder

- Van Helsing

- The Night Comes for Us

- Code of Silence

- Captain Ron

- Armageddon

- Kate’s Secret

- Point Break

- The Replacements

- The Shadow

- Meteor

- Last Action Hero

- Attack of the Killer Tomatoes

- The Horror at 37,000 Feet

- The ‘Burbs

- Lifeforce

- Highschool of the Dead

- Ice Station Zebra

- No One Lives

- Brewster’s Millions

Hey, California! Are you ready to soft rock!?

Hey, California! Are you ready to soft rock!?