“Revenge reveals the darkest reflection we hide within.”

Horror cinema has long functioned as a reflective surface, exposing humanity’s deepest fears, desires, and moral uncertainties. The films I Saw the Devil (2010), Cold Fish (2010), and Revenge (2017) serve as “blood mirrors,” revealing not merely the visceral violence inflicted upon their characters but also the profound psychological and ethical transformations that vengeance ignites. Emerging from South Korean, Japanese, and French cinematic traditions, respectively, these works reconceptualize the trauma of retribution into nuanced explorations of identity, power, justice, and morality. This essay unpacks how such acts of revenge fracture and distort the avengers themselves—blurring the boundary between hunter and hunted—and challenge audiences to consider the complicated ethics of vengeance.

Becoming the Monster: I Saw the Devil and the Infinite Cycle of Vengeance

Kim Jee-woon’s I Saw the Devil opens with searing loss. Government agent Kim Soo-hyun’s fiancé is gruesomely murdered by the psychopathic serial killer Jang Kyung-chul. Rather than delivering immediate justice, Kim embarks upon a merciless cycle of capture and release aimed not at ending Kyung-chul’s life but extending his suffering to mirror the anguish Kim feels. This circular vengeance becomes a vehicle for exploring grief’s corrosive power, blurring the avenger’s and victim’s identities.

The film’s structure, with its repetitive cat-and-mouse dynamic, becomes a visual metaphor for obsession and moral degradation. With every brutal encounter, Kim sacrifices more of his humanity, evolving into the very monster he’s vowed to destroy. Lee Mo-gae’s cinematography blends stark clinical detachment with visceral brutality; meticulously framed shots contrast vividly with the film’s emotional chaos, compelling the audience into uncomfortable identification with Kim’s dark crusade. The snowy landscapes and cold colors evoke spiritual desolation, emphasizing the film’s existential chill.

Kim’s work transcends procedural thriller conventions by resisting catharsis—vengeance is portrayed not as liberation but endless torment. Critics laud the film for masterfully challenging traditional revenge narratives by suggesting that acts of retribution can perpetuate cycles of violence, consuming both victim and perpetrator. The tension not only lies in physical danger but in the moral disintegration of a man who becomes what he hates.

Hidden Rage Beneath Ordinary Lives: Social Collapse in Cold Fish

Sion Sono’s Cold Fish presents revenge as an eruption of buried rage within the façade of mundane suburban existence. The gentle tropical fish store owner, Nobuyuki Syamoto, leads a restrained, law-abiding life until meeting the domineering and psychopathic Murata. Their relationship becomes a dance of psychological and physical domination, exposing latent violence simmering under cultural conformity.

Unlike the clinical precision of I Saw the Devil, Cold Fish captures chaos and collapse. Syamoto’s eventual violent revolt is neither heroic nor cathartic but an enactment of existential despair born of oppressive social codes emphasizing politeness, hierarchy, and silence. The oppressive suburban setting becomes almost a character itself—sterile, suffocating, and emotionally barren. The circling fish motif highlights the recursive cycles of repression and violence that trap the characters.

Sono’s cinematic approach balances absurdist, at times black humor with grim horror. This tonal dissonance destabilizes viewer complacency, forcing reflections on how individual suffering is structured and concealed by social and cultural norms. Syamoto’s dissolution challenges viewers to reconsider traditional narratives of justice and victimhood, emphasizing the fragility of identity under systemic pressures.

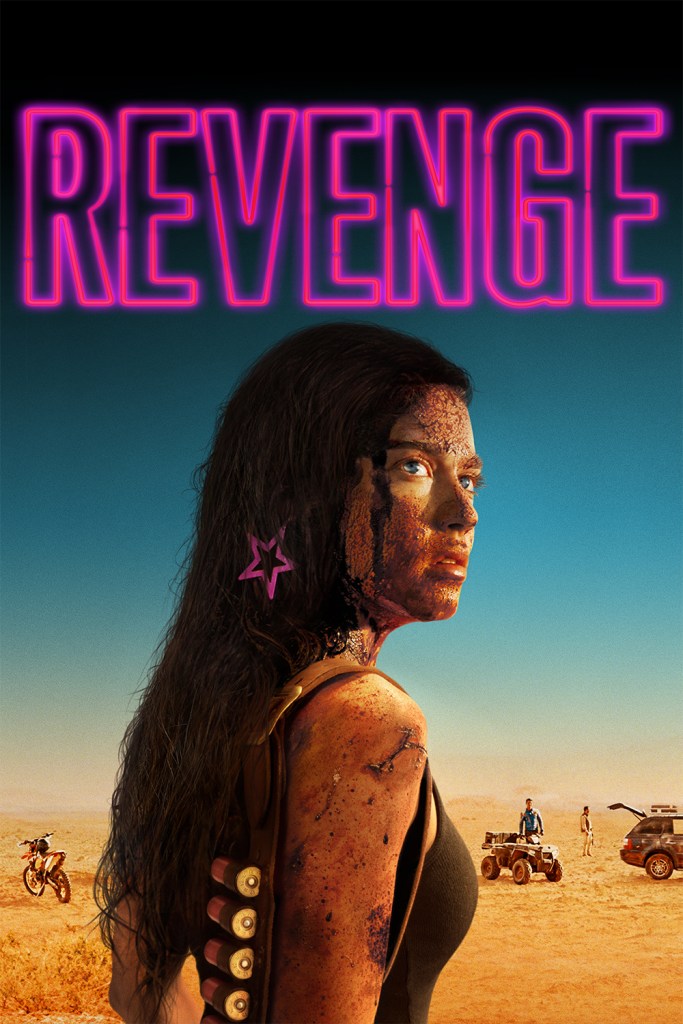

From Exploitation to Empowerment: Revenge and the Reclamation of Agency

Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge radically revisits the “rape and revenge” genre notorious since 1970s grindhouse cinema. While drawing inspiration from films like I Spit on Your Grave and The Last House on the Left, Revenge rejects those works’ often exploitative male gaze, recasting the survivor’s story through a fully realized lens of autonomy and violent reclamation.

Jen’s transformation—from a sexualized object within a hyper-saturated, colorful visual palette to a mythic force of nature marked by the symbolic phoenix brand—signifies death and rebirth. Fargeat’s use of chiaroscuro lighting, surreal settings, and visceral violence elevates physical trauma to the level of mythic metamorphosis.

This film subverts traditional victim and villain binaries. Jen’s ascent dismantles deeply embedded patriarchal structures, underscoring a reclamation of body, gaze, and power. The climactic chase, drenched in blood and primal energy, becomes a ritualistic unshackling rather than mere revenge. Through this revival of grindhouse aesthetics, Fargeat forges a new grammar of feminist survival and cinematic empowerment.

Power, Gender, and Hierarchies in Contemporary Revenge Narratives

These films foreground power dynamics traditionally gendered but reinterpreted here in ways promoting gender-neutral critique. In Cold Fish, toxic masculinity manifests as violent domination versus passivity within strict social codes, both Syamoto’s submission and Murata’s cruelty reinforcing systemic violence.

I Saw the Devil portrays injured masculine pride and control as drivers of vengeance. Kim’s obsession symbolizes fragile protector ideals collapsing into moral ruin. Female characters often exist as symbolic voids, underscoring systemic gender violence and erasure.

Revenge, by contrast, deconstructs these codes. Jen transcends rigid gender norms and victimhood, suggesting power as a fluid, elemental force beyond biology. The film’s desert setting serves as a symbolic womb of transformation, projecting possibilities of autonomy and sovereignty through defiance of hierarchical structures.

National Contexts: Morality, Control, and Crisis

Each film emerges from distinct cultural anxieties and historical trajectories. I Saw the Devil reflects South Korean skepticism about institutional justice amid rapid modernization and lingering traditionalism. Private vengeance becomes a desperate, isolating reaction to systemic failure.

Cold Fish critiques a Japanese culture steeped in social conformity and emotional repression, revealing the violent potential beneath controlled civility. The film reflects post-war tensions and growing awareness of societal alienation.

France’s Revenge draws from the New Extremity movement, blending philosophical and visceral approaches to suffering, reflecting intellectual and artistic responses to modern oppression. Fargeat’s fusion of grindhouse with feminist critique signals contemporary cultural struggle for voices outside dominant systems.

Narrative and Visual Style: Diverse Paths to Transformation

The narrative architectures differ but complement one another. I Saw the Devil’s repetitive structure illustrates cyclical moral decay; Cold Fish depicts downward spiral into absurd chaos; Revenge follows mythic death-and-rebirth arc.

Their visual languages communicate complex ethical positions: Kim’s symmetrical, controlled shots reflect calculated cruelty; Sono’s frenetic, disorienting camera work conveys mental disintegration; Fargeat’s vivid, stylized imagery channels surreal transcendence.

Each film implicates the viewer uniquely. I Saw the Devil seduces with calculated violence; Cold Fish overwhelms with chaotic brutality; Revenge reorients the gaze empathetically to survivor experience. Together, they articulate a profound inquiry into horror spectatorship and ethical engagement.

Societal Reflections: Alienation and Moral Fragmentation

These films manifest collective crises of modernity—gendered hierarchies, failed justice, fractured communities—within intimate personal revenge stories. They diagnose alienation and fragmentation, transforming revenge into language for voicing trauma and injustice. This intersection exposes how power, violence, and identity intertwine in contemporary cultural narratives.

The Horror of Becoming

Ultimately, I Saw the Devil, Cold Fish, and Revenge frame horror as a meditation on transformation rather than pure evil. Vengeance reshapes the self, often toward destruction. Kim becomes the hunted devil; Syamoto lives his oppressor’s violence; Jen transcends human limits through fiery renewal.

Together, they depict revenge as curse, collapse, and painful rebirth—a global meditation on violence and selfhood. Their shared revelation: revenge unmasks the darkness dwelling quietly within us all, proving that horror’s deepest mirror reflects ourselves.