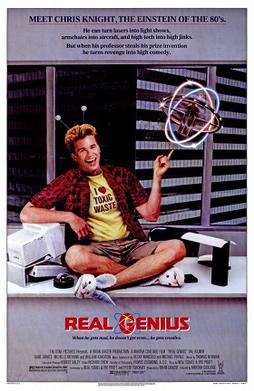

Evil businessman John Pilgrim (Nicholas Pryor) and his assistant Brooke Alistair (Lance Henriksen) want to turn Utah’s Choke Canyon into a dumping ground for toxic waste. The only problem is that Dr. David Lowell (Stephen Collins), a cowboy scientist, has signed a 99-year lease and is using the canyon as a place to conduct experiments that are designed to turn the soundwaves from Halley’s Comet into an alternative energy source. Pilgrim sends pilot Oliver Parkside (Bo Svenson) to get Lowell out of the canyon by any means necessary. However, Pilgrim’s rebellious daughter, Vanessa (Janet Julian), has also gone to the canyon because she finds Dr. Lowell to be intriguing. Lowell’s reaction is to kidnap Vanessa and hold her hostage but, of course, they fall in love while trying to fly a giant ball of toxic waste out of the canyon.

Evil businessman John Pilgrim (Nicholas Pryor) and his assistant Brooke Alistair (Lance Henriksen) want to turn Utah’s Choke Canyon into a dumping ground for toxic waste. The only problem is that Dr. David Lowell (Stephen Collins), a cowboy scientist, has signed a 99-year lease and is using the canyon as a place to conduct experiments that are designed to turn the soundwaves from Halley’s Comet into an alternative energy source. Pilgrim sends pilot Oliver Parkside (Bo Svenson) to get Lowell out of the canyon by any means necessary. However, Pilgrim’s rebellious daughter, Vanessa (Janet Julian), has also gone to the canyon because she finds Dr. Lowell to be intriguing. Lowell’s reaction is to kidnap Vanessa and hold her hostage but, of course, they fall in love while trying to fly a giant ball of toxic waste out of the canyon.

Directed by the legendary stuntman Charles Bail, Choke Canyon is at its best when it focuses on Parkisde using his plane to chase Lowell’s helicopter. Some of the aerial sequences are really exciting, even if they don’t make much sense. (Surely, someone as powerful and rich as John Pilgrim could have afforded to send more than three guys and a cropduster to take care of Lowell.) Stephen Collins, years before his career would collapse after he admitted to inappropriately touching three minor-aged girls, is as personable and bland here as he was in the first Star Trek movie. The idea of a cowboy scientist is interesting but Collins really didn’t have the screen presence to pull it off. It doesn’t help that Collins was having to act opposite a certifiable badass like Bo Svenson. This is one of the rare movies where I wanted the bad guys to win because they were just so much cooler than the hero.

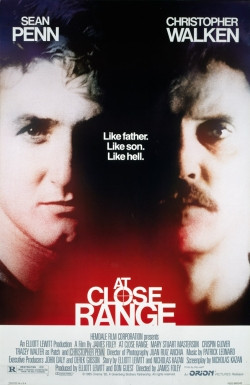

Some of the stunts are impressive, as they should be with Chuck Bail behind the camera. Stephen Collins is boring and Janet Julian feels miscast. (She would give a much better performance as Christopher Walken’s lawyer and girlfriend in King of New York.) I don’t understand how a power source based on Halley’s Comet would work. It might have worked for a few months in 1986 but what are they going to for energy until 2061 rolls around?