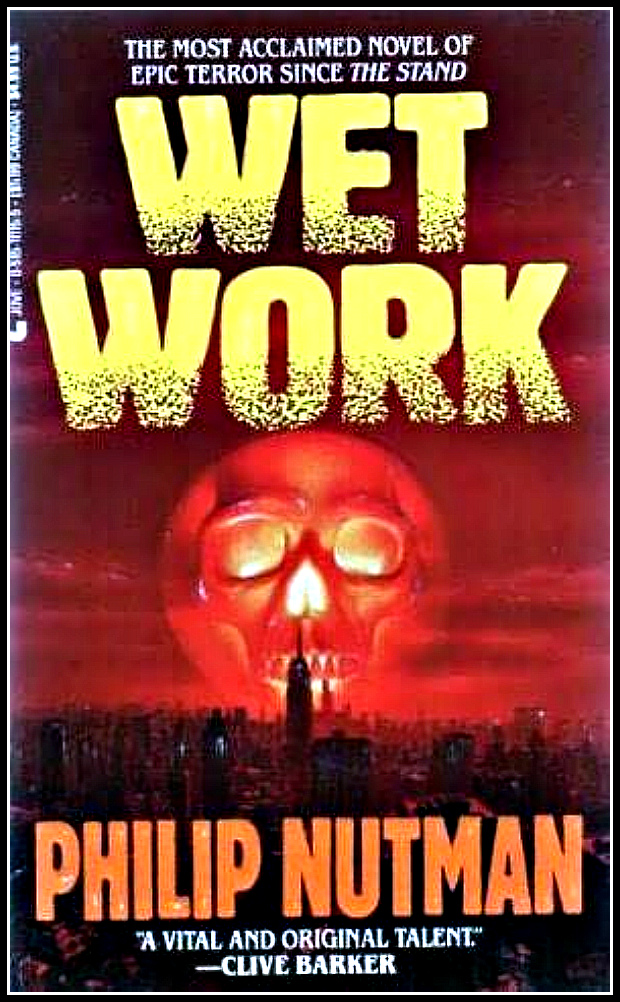

“Wet work” – intelligence community slang for covert operations involving assassination or killing, named for the ‘wet’ bloodshed such missions entail.

Philip Nutman isn’t a name most readers recognize outside of hardcore horror and zombie fiction circles, but within those communities, he’s remembered as an accomplished writer and journalist who carved out a unique space in the genre. For most of his career, Nutman worked as a freelance media journalist and film critic, contributing to magazines like Fangoria and Cinefantastique, where he covered the darker corners of cinema. As a fiction writer, he didn’t produce much in the way of novels, but the one he did publish—Wet Work (1993)—earned him lasting respect among fans who prefer their horror mixed with high-stakes action and cynical political undertones.

Wet Work began as a short story published in George A. Romero and John Skipp’s 1989 anthology Book of the Dead, a milestone collection that helped define zombie fiction as something literary rather than purely pulp. Even within that assembly of strong voices, Nutman’s story stood out for combining government espionage with apocalyptic horror. Expanding it into a full novel only amplified those elements, turning what had been a grim short tale into something closer to an action-horror epic with splatterpunk guts and a spy thriller’s pacing.

The novel opens with CIA operative Dominic Corvino, a member of an elite black-ops unit called Spiral, barely surviving a mission gone wrong in Panama City. From the start, Nutman gives the story a sense of distrust and paranoia—Corvino believes his team was deliberately sabotaged, their deaths engineered by someone inside the CIA. It’s an opening that reads more like a Cold War spy novel than a zombie tale, and that mix of tones is part of what makes Wet Work work so well. Nutman uses what he likely learned as a journalist—his knack for detail, the sense of how bureaucracies function (or fail to)—to give the early chapters an almost procedural authenticity. There’s a lived-in realism to the military and intelligence backdrop that keeps even the most outrageous elements of the story grounded.

Then comes the moment that shifts Wet Work from gritty reality into nightmarish surrealism. As the CIA plotline unfolds, a cosmic event takes place: the comet Saracen passes dangerously close to Earth and leaves behind some kind of invisible residue. It’s never fully explained whether it’s chemical, biological, or something beyond understanding, but its aftereffects begin to change life on the planet. Nutman uses the comet not just as a plot trigger but as a symbol of inevitability—a reminder that humankind’s end won’t always come from weapons or war, but sometimes from something as impersonal as celestial dust. It’s a bit of cosmic horror filtered through the lens of political and societal collapse, an end-of-days scenario that feels both mythic and strangely plausible.

Meanwhile, in Washington D.C., police officer Nick Packard becomes the reader’s main point of connection to the chaos on the ground. Packard starts the day leading a routine shift through the usual headaches of the city, but things unravel fast once Saracen’s effects take hold. Strange attacks start flooding police dispatch, cases of violence erupting in ways no one can explain, and what seem like random acts of brutality turn out to be part of something much larger. The city descends into panic as the dead begin returning to life. Nutman describes this breakdown with a sense of escalating dread that feels almost journalistic—each detail adds up, each scene observed as though through the eyes of someone trying to make sense of something senseless.

The zombies themselves are mostly what readers might expect from stories inspired by George A. Romero: slow-moving, decomposing, and relentless. But Nutman complicates things by hinting that not all of the reanimated are mindless. Some seem to retain fragments of human cunning or memory, enough to make them unpredictable and far more dangerous. This small twist gives the book a chilling edge, making it clear that intelligence doesn’t necessarily counteract monstrosity—it might even make it worse.

Corvino’s section of the novel runs parallel to Packard’s and serves as the darker, more psychological side of the story. He becomes consumed by his mission to find out who betrayed his team in Panama and make them pay. Physically, he’s battered and near his limits, operating in a world that no longer follows the rules of logic or hierarchy. Mentally, he’s trapped between loyalty, fury, and isolation—an operative trained for controlled violence now facing chaos that no training can manage. Nutman writes Corvino as a man unraveling in sync with the world around him. His search for answers feels less like a mission and more like an obsession, a desperate grasp at clarity in a world that’s literally stopped making sense.

Packard’s story, by contrast, brings everything down to a more personal survival narrative. As the crisis worsens, his only goal becomes reaching his wife, stranded in their suburban home outside the city. His journey across a collapsing Washington D.C. is one of the novel’s strongest threads, combining small moments of human connection with scenes of escalating horror. Through him, the reader gets a street-level view of societal breakdown—communications dying, infrastructure collapsing, and people reacting in unpredictable, often violent ways. What makes Packard’s arc compelling is its simplicity; amid government conspiracies and cosmic cataclysms, his is just a story about trying to save someone he loves.

Eventually, Corvino’s and Packard’s paths intersect, and both men come face to face with what’s left of the government. By this stage, authority itself has become just another form of predation. The people who once held power have adapted frighteningly well to the new world, shedding morality and decency like dead skin. Nutman doesn’t paint them as comic-book villains but as survivors whose ethics erode one decision at a time. In typical splatterpunk fashion, the line between humanity and monstrosity blurs completely.

Nutman’s writing in Wet Work is graphic, fast-moving, and unflinching. His descriptions of violence and gore are vivid without slipping into parody, and even when the pacing turns frenetic, it matches the story’s collapse into total madness. Where he stumbles is in a few awkward moments of dialogue and some stilted attempts at sexuality—scenes that read more forced than provocative. But those missteps never fully pull the story off course. If anything, they serve as reminders that Nutman, for all his journalistic precision, was still finding his rhythm in long-format storytelling.

The novel embodies everything bold about early 1990s horror fiction: big ideas, unrestrained violence, and a willingness to splice genres that didn’t normally coexist. Wet Work could just as easily sit beside Dawn of the Dead as it could a paranoid spy novel from the 1980s. Nutman understood that the systems people depend on—government, military, media—are fragile constructs that crumble the second survival becomes personal. That realism, drawn from his background in journalism, grounds the chaos he unleashes. Even at its most supernatural, Wet Work feels uncomfortably plausible because its human failures ring true.

After Wet Work, Nutman shifted back toward shorter forms, writing comics, novellas, and media journalism rather than more novels. In hindsight, that makes his one major book feel all the more significant. It’s the place where all his skills—his eye for detail, his fascination with moral gray areas, and his love of horror excess—come together.

For zombie fiction fans, Wet Work remains a hidden gem worth revisiting. It’s not just a gore-fest or survival tale but a demonstration of how horror doesn’t need to stay confined within its own walls. Nutman showed that the genre can bleed into others—melding espionage, political thriller, and cosmic dread into something distinct and alive. In a field that sometimes plays it safe, Wet Work reminds readers that horror thrives on experimentation, that it’s strongest when it’s hybridized and unpredictable. With Nutman’s death in 2013, any chance of seeing another full-length novel from him is gone, but what remains is proof that horror, when unafraid to evolve, can be far more than blood and fear—it can be reinvention itself.