“And kill any officer in sight. Ours or theirs?” — Victor Franko

The Dirty Dozen is one of those war movies that feels like it was built in a lab for maximum “guys-on-a-mission” entertainment: big stars, a pulpy premise, plenty of attitude, and a third act that goes full-tilt brutal. It is also, even by 1967 standards, a pretty gnarly piece of work, and how well it plays today depends a lot on how comfortable you are with its mix of macho camaraderie, anti-authoritarian swagger, and disturbingly gleeful violence.

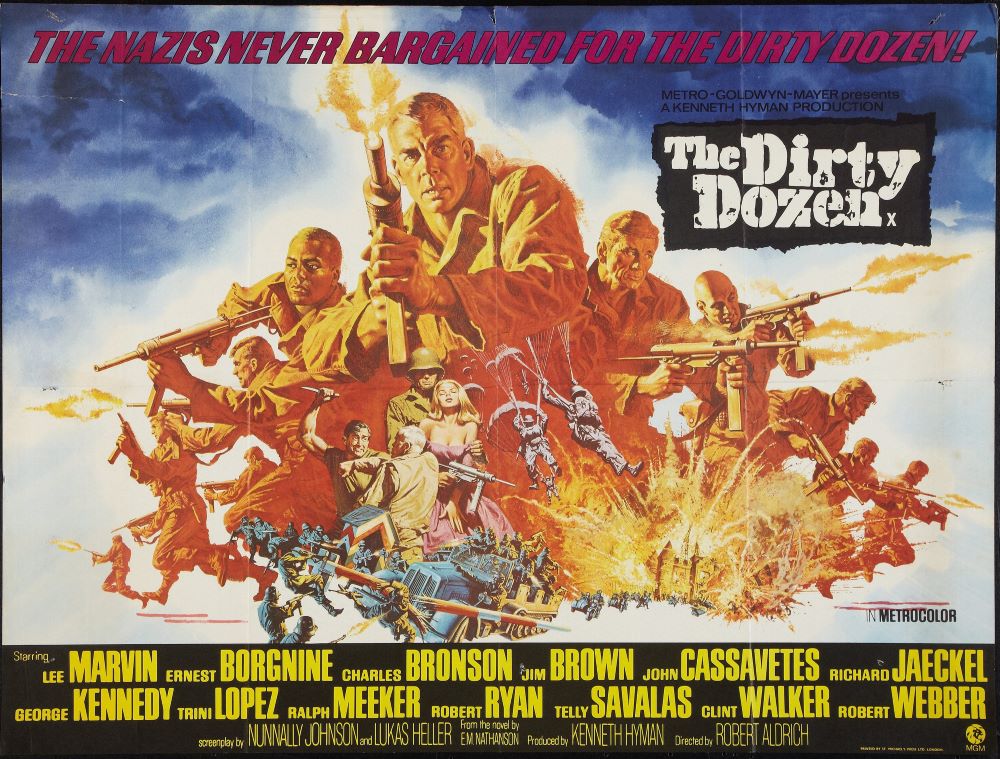

Directed by Robert Aldrich and released in 1967, The Dirty Dozen is set in 1944 and follows Major John Reisman (Lee Marvin), a rebellious U.S. Army officer assigned to turn a group of twelve military convicts into a commando unit for a suicide mission behind enemy lines just before D-Day. The deal is simple and grim: survive the mission to assassinate a gathering of German high command at a chateau, and your death sentence or long prison stretch gets commuted; fail, and you die as planned, just a little earlier and with more explosions. It is a high concept that plays almost like a war-movie prototype of the “villains forced to do hero work” formula that modern blockbusters keep revisiting.

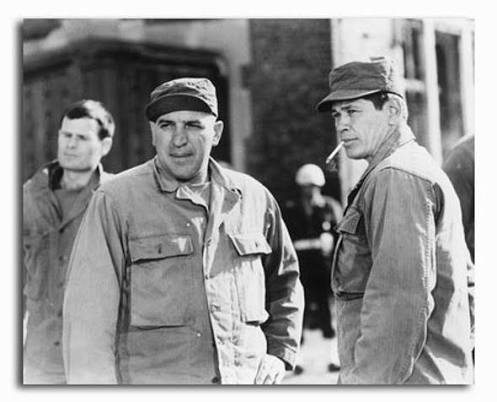

The film’s biggest asset is its cast, stacked with personalities who bring a rough, lived-in charm to what could have been a lineup of interchangeable tough guys. Lee Marvin’s Reisman is the glue: a cynical, gravel-voiced officer who clearly hates bureaucratic brass almost as much as the criminals he is supposed to whip into shape, and Marvin plays him with a dry, weary sarcasm that avoids hero worship even as the film asks you to root for him. Around him, you get Charles Bronson as Wladislaw, a capable former officer with a chip on his shoulder; John Cassavetes as Franko, the volatile, insubordinate troublemaker; Jim Brown as Jefferson, whose physical presence and final-act heroics leave a strong impression; and Telly Savalas as Archer J. Maggott, a violently racist, fanatically religious, and almost certainly deranged soldier sentenced to death for raping and beating a woman to death. Savalas never softens that portrait, playing Maggott with a creepy combination of sing-song piety and sudden bursts of viciousness that makes him deeply uncomfortable to watch and the one member of the Dozen who feels like an outright monster even compared to the other killers. He sells Maggott’s self-justifying religiosity—quoting scripture, talking about being “called on” by the Lord—as both delusional and dangerous, so every time he starts sermonizing, it feels like a warning siren that things are about to go bad, and that pays off in the finale where his obsession with “sinful” women sabotages the mission. Even smaller roles from Donald Sutherland, Clint Walker, and others get memorable beats, which helps the ensemble feel like an actual crew rather than background noise.

For much of its runtime, the film plays like a rough-and-rowdy training camp movie, and that middle stretch is where a lot of its charm sits. Reisman’s solution to building teamwork is basically to grind the men down, deny them basic comforts, and force them to build their own camp, leading to the nickname “the Dirty Dozen” when their shaving kits are confiscated and they slip into permanent grime. The squad slowly gels through a mix of forced labor, competitive drills, and a memorable war-games exercise where they outsmart a rival, straight-laced unit led by Colonel Breed (Robert Ryan), which lets the film indulge in its anti-authority streak by making the rule-breakers look smarter than the regulation-obsessed brass. Savalas’s Maggott adds a constant sense of volatility to these scenes, his presence giving the group dynamic a genuine horror edge that keeps the movie from becoming a simple “lovable rogues” fantasy and making viewers eager to see him punished.

That anti-establishment energy is one of the reasons The Dirty Dozen hit so hard with audiences in the late 1960s, especially as public attitudes toward war and authority were shifting in the shadow of Vietnam. The movie clearly enjoys showing higher-ranking officers as petty, hypocritical, or out of touch, while Reisman and his misfit killers get framed as the ones who actually understand how war really works: dirty, improvisational, and morally compromised. Critics at the time noted that this defiant attitude, coupled with the convicts’ transformation into rough heroes, gave the film a rebellious appeal that helped it become a box office smash even as traditional war films were losing their shine.

Where the film becomes more divisive is in its moral perspective, or arguably its lack of one. From the start, these are not misunderstood saints: several of the men are condemned to death for murder, others for violent crimes and serious offenses, and the script never really suggests they were framed or unfairly treated. Yet once they are pointed at Nazis, the movie largely invites you to cheer them on, leaning into the idea that in war, the ugliest tools might be the most effective, and that conventional standards of justice and morality can be suspended if the target is the enemy. Maggott stands apart here as the line the film refuses to cross into sympathy, with Savalas’s committed and unsettling performance underlining how poisonous he is even to other criminals.

The climax at the chateau is where this tension really spikes. The mission involves infiltrating a mansion where German officers and their companions are gathering, rigging the place with explosives, and driving the survivors into an underground shelter that is then sealed and turned into a mass deathtrap with gasoline and grenades. It is a sequence staged with brutal efficiency and undeniable suspense, but it is also deeply unsettling, essentially pushing the protagonists into orchestrating a massacre that includes unarmed officers and civilians in evening wear, and the film offers minimal reflection on that horror beyond the visceral thrills. Maggott’s instability forces the team to react mid-mission, heightening the jagged tonal mix of rousing action and casual atrocity.

This blend of rousing action and casual atrocity did not sit well with many critics in 1967. Contemporary reviews complained that the film glorified sadism, blurred the line between wartime necessity and psychopathic cruelty, and practically bathed its criminals “in a heroic light,” encouraging what one critic called a “spirit of hooliganism” that was socially corrosive. Others, however, praised Aldrich for making a tough, uncompromising adventure picture that pushed back against sanitized war clichés, arguing that the cruelty and amorality felt like a more honest reflection of war’s ugliness, even if the film coated it in action-movie swagger and gallows humor. Savalas’s Maggott amplifies this debate, singled out by fans as a great, memorable character who adds real repulsion without turning into a cartoon.

From a modern perspective, the violence itself remains intense but not especially graphic by contemporary standards; what lingers is the attitude around it. The movie’s glee in letting some of these characters off the moral hook, contrasted with the genuinely disturbing behavior of someone like Maggott, creates that jagged tonal mix: part old-school “men on a mission” yarn, part cynical commentary on the kind of men war turns into tools. Depending on your tolerance, that mix either gives the film an edge that keeps it from feeling like simple nostalgia, or it plays as carelessly flippant about atrocities that deserve more introspection than a last-minute body count and a fade-out.

On a craft level, though, The Dirty Dozen still works surprisingly well. Aldrich keeps the film moving across a long runtime by building distinct phases: the recruitment and introduction of each convict, the training and bonding section with its rough humor and humiliation, and the final mission that shifts into suspense and near-horror. The action is clear and muscular, the editing sharp enough that you rarely lose track of who is where, and the sound design—even recognized with an Academy Award for Best Sound Effects—helps the chaos of the finale land with blunt impact.

At the same time, the structure exposes a few weaknesses. The early sections do such a good job of sketching out personalities that some characters feel underused or abruptly sidelined once the bullets start flying, and the film’s length can make parts of the training montage drag, especially if you are less enamored with its barracks humor and macho posturing. The writing also leans on broad types—psychopath, wisecracking crook, stoic professional—which the cast elevates, but the script rarely pushes them into truly surprising territory, beyond a few late-movie acts of sacrifice.

Still, as a piece of war-movie history, The Dirty Dozen earns its reputation. It helped popularize the template of the misfit team thrown into an impossible mission, a structure that later shows up everywhere from ensemble war pictures to superhero teams and modern “suicide squad” stories. Its mix of black humor, anti-authoritarian streak, and violent catharsis captures a specific late-1960s mood, even as its politics and ethics remain muddy enough to spark debate decades later. Savalas’s turn as Maggott ensures that edge never dulls, keeping the film’s thrills packaged with a moral outlook as messy and conflicted as the men it sends to kill.

For someone coming to it fresh now, the film plays as a rough, sometimes exhilarating, sometimes queasy ride: entertaining as pulp, compelling as an ensemble showcase, and troubling in the way it treats brutality as both a necessary evil and a spectator sport. If you are interested in the evolution of war cinema or the origins of the “ragtag squad on a suicide mission” trope, The Dirty Dozen is absolutely worth watching, with the understanding that its strengths—like Savalas’s chilling Maggott—come wrapped in those ethical ambiguities.