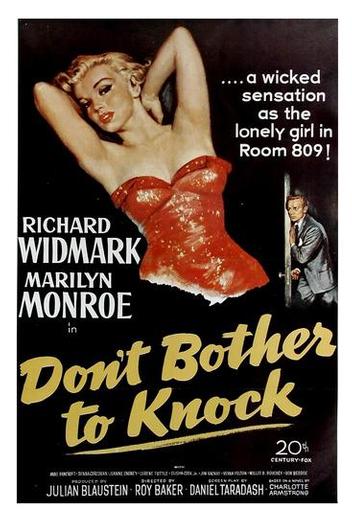

(I am currently attempting to clean out my DVR. I recorded the 1952 film Don’t Bother To Knock off of FXM on April 3rd.)

Welcome to the McKinley Hotel in New York City! The McKinley is a nice place, though it’s no Grand Budapest Hotel. Presumably, the McKinley was named after the late President William McKinley. While I’m sure that McKinley would have appreciated the gesture, I don’t know how he would feel about all the melodrama that’s occurring behind closed doors.

For instance, there’s Lyn Lesley (Anne Bancroft, making her screen debut). Lyn sings in the hotel bar and, though she might seem to be cynical and tough, she actually has a big heart. In fact, she cares so much about humanity that she broke up with her longtime boyfriend, Jed Towers (Richard Widmark), because he doesn’t seem to have a heart at all. Of course, she broke up with Jed by sending him a letter. When Jed checks into the hotel and tracks her down in the bar, he has questions about their breakup and he wants answers that won’t require any reading. She tells him that he’s not capable of caring about anyone so why should she waste her time on him? Then she sings a love song because that’s her job.

As for Jed, he’s kind of a jerk in the way that most men tend to be in movies from the 1950s. He’s an airline pilot who served overseas during World War II and spent a year living in England. He’s tough and he’s cynical and now, he’s single. He’s also got a room in a hotel for the night.

And then there’s Peter and Ruth Jones (Jim Backus and Lurene Tuttle), who have a function to attend in the hotel ballroom but who don’t have anyone to look after their ten year-old daughter, Bunny (Donna Corcoran). Fortunately, the hotel’s elevator operator, Eddie (Elisha Cook, Jr.), has a niece named Nell (Marilyn Monroe). Nell is quiet and shy and needs the money. She’ll be more than willing to babysit!

Of course, the only problem with Nell is that she’s a little unstable. This becomes obvious when she’s left alone with Bunny and promptly says that, if Bunny isn’t careful, something bad might happen to one of her toys. Inside the apartment, Nell is impressed by all the pretty things owned by Ruth. She tries on her jewelry. She sprays her perfume in the air. She puts on Nell’s negligee and looks at herself in the mirror. Eddie is not amused when he discovers what Nell’s been doing. If she wants all of this stuff, he tells her, she needs to marry someone rich. That’s not bad advice but the only problem is that Nell is currently single. She’s been single ever since her boyfriend died in a plane crash. In fact, Nell was so upset by his death that she even tried to commit suicide afterward.

From his room, Jed has a direct view of Nell trying on Ruth’s clothes. When he and Nell spot each other, Nell invites him over. She tells Jed that she’s a guest at the hotel and that Bunny is her daughter. Jed can immediately tell that there’s something strange about Nell. Nell, meanwhile, thinks that Jed is her dead boyfriend. Meanwhile, Bunny is helpless in her room…

Clocking in at a brisk 72 minutes, Don’t Bother To Knock feels less like a movie and more like a one-act play or maybe even an adaptation of an old television production. (After watching the movie, I was shocked to discover that it was based on neither.) Seen today, it’s mostly memorable for featuring Marilyn Monroe’s first true starring role. After appearing in small roles in several films (including All About Eve), Don’t Bother To Knock was not only Marilyn’s shot at stardom but also her first dramatic performance. Reportedly basing her performance on her troubled mother, Marilyn is sympathetic and almost painfully vulnerable. Her scenes with Elisha Cook, Jr. are especially charged, full of a subtext that will probably be easier for modern audiences to spot than it was for audiences in 1952. Marilyn gave an incredibly poignant performance and she is the main reason to watch Don’t Bother To Knock.