“You’re diving deeper than any sane man ever should.” — Dr. Katherine McMichaels

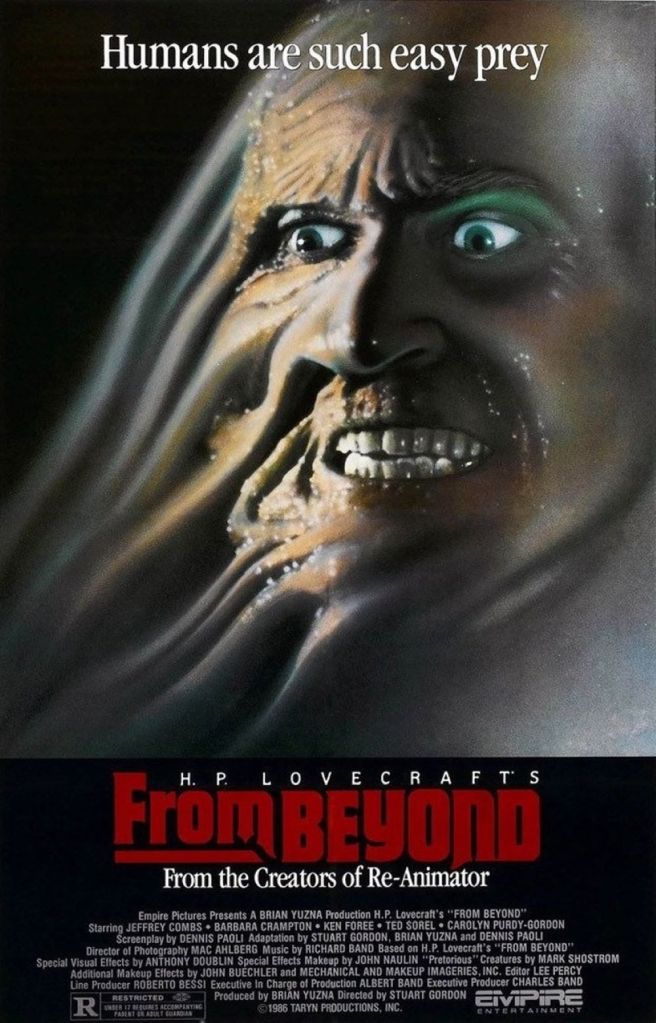

Stuart Gordon’s From Beyond (1986) stands as a darker, moodier follow-up to his breakout Lovecraft adaptation, Re-Animator (1985). At its core is the Resonator, a bizarre scientific contraption designed to stimulate the pineal gland—allowing its users to glimpse eerie creatures and dimensions normally invisible to the naked eye. When Dr. Crawford Tillinghast (Jeffrey Combs) activates the device, it unleashes horrors not just upon the world but also within the minds and bodies of those involved, blurring the line between reality and nightmare in a way both terrifying and hypnotic.

Just like with Re-Animator, Gordon used H.P. Lovecraft’s short story From Beyond as a foundation but expanded the narrative significantly by injecting his own creative vision and filling in what Lovecraft left unexplored. Lovecraft’s original story is a brief, eerie vignette about stimulating the pineal gland to perceive alternate dimensions and terrifying alien creatures—minimalistic and atmospheric, leaving much to the imagination. Gordon reimagines this premise into a fully fleshed-out narrative, adding complex characters like the obsessive Dr. Edward Pretorius and the rational yet vulnerable Dr. Katherine McMichaels. He enriches the story with body horror, psychological torment, and a deeper thematic exploration of sexuality, obsession, and the fragility of the mind. This creative expansion transforms the story into something far more personal and tangible, blending cosmic horror with primal human fears and desires.

This tonal shift stands in stark contrast to Re-Animator, which thrives on anarchic gore, slapstick comedy, and a playful mad-scientist energy. From Beyond trades much of the humor for a somber, unsettling atmosphere drenched in slime, grotesque transformations, and claustrophobic dread. The characters are more grounded in psychological trauma, and the film’s pacing emphasizes creeping unease rather than chaotic spectacle. Gordon’s use of stark, hallucinatory lighting and saturated colors enhances this otherworldly feeling, while practical effects bring a tactile horror to life that heightens the visceral and emotional impact. The horror isn’t just external—it’s internal, a fracture of reality and self.

One of the most notable ways From Beyond separates itself from Gordon’s earlier work is in its overt intertwining of sexuality and horror. The Resonator doesn’t just expose alien creatures; it unlocks primal lust and repressed desires in its users. Scenes imbued with uneasy erotic tension, especially involving Barbara Crampton’s character, make sexuality a core source of vulnerability and terror. This blend of eroticism and nightmare adds depth and psychological complexity, exploring how intimate human experiences can be distorted into something terrifying. It’s a thematic boldness that would become highly influential beyond Western cinema.

Indeed, the film’s fusion of sexual subtext, body horror, and psychological unease foreshadowed themes embraced by late 1980s and early 1990s Japanese horror hentai anime. Works such as Angel of Darkness (Injū Kyōshi) combined explicit eroticism, grotesque body transformations, and supernatural horror in ways reminiscent of From Beyond’s style and tone. This synergy helped define a subgenre of adult horror anime where the boundaries between pleasure and terror, desire and monstrosity, are constantly blurred—cementing From Beyond not only as a cult classic in horror but also as an inspirational bridge to pioneering adult animation in Japan.

Visually and atmospherically, the film is a masterpiece of practical effects and immersive storytelling. The slime-drenched creatures, anatomically warped bodies, and constant visual flow between nightmare and distorted reality create a hallucinatory experience. The climax offers a frenetic, visceral battle that embodies the film’s core themes of madness, transformation, and cosmic terror, leaving viewers with a lingering sense of unease and wonder.

Stuart Gordon’s direction also employs incredibly effective subjective perspectives, with many scenes shot from the characters’ points of view. This technique immerses viewers in the unfolding madness and heightens the sensory overload that defines the film’s experience. There is a famously unsettling point-of-view shot from the mutated Crawford as he perceives a brain inside a doctor’s head and gruesomely attacks. Such moments amplify the film’s exploration of altered perception and the treacherous expansion of human senses.

Despite these strengths, the film is not without flaws. Ken Foree’s character, Bubba Brownlee, while providing moments of grounded streetwise humor, sometimes comes off as a caricature that leans into stereotypical portrayals of Black men as taboo or outlier figures in horror cinema. This portrayal feels somewhat jarring against the film’s otherwise nuanced tone and may evoke discomfort.

Additionally, From Beyond can feel comparatively stiff and sluggish next to Re-Animator, lacking some of the earlier film’s darkly comic energy. The story often relies on a series of increasingly grotesque set pieces that feel more like shock showcases than a cohesive narrative arc. Some performances, including Jeffrey Combs’ lead, occasionally seem overly intense without sufficient emotional variation, and the film sometimes slips into melodrama that undercuts its impact. Furthermore, although ambitious in visualizing Lovecraftian horrors, budgetary constraints are occasionally evident, diminishing some of the awe those moments seek to inspire.

Ultimately, Gordon’s From Beyond is a significant Lovecraft adaptation that showcases the power of expanding upon source material with bold creativity. Moving beyond Lovecraft’s sparse prose, Gordon infuses the story with rich characters, psychological depth, explicit body horror, and mature explorations of sexuality. This results in a haunting, distinctly unsettling film that not only stands as a high point in Gordon’s career but also resonates far beyond its American horror roots, shaping international horror aesthetics and inspiring future genres. It is a disturbing, thrilling journey to the dark spaces just beyond human perception—a cinematic experience that lingers in the mind long after the screen fades to black.

Michael (William Bumiller) owns the hottest health club in Los Angeles but that may not stay true if he can’t do something about all the guests dying. Members get baked alive in the sauna. Another is killed when a malfunctioning workout machine pulls back his arms and causes a rib to burst out of one side of his body. Shower tiles fly off the wall and panic a bunch of naked women. A woman loses her arm in a blender and a man is somehow killed by a frozen fish. Strangely, all of the deaths don’t seem to hurt business as people still keep coming to the gym. Surely, there are other, safer health clubs in Los Angeles.

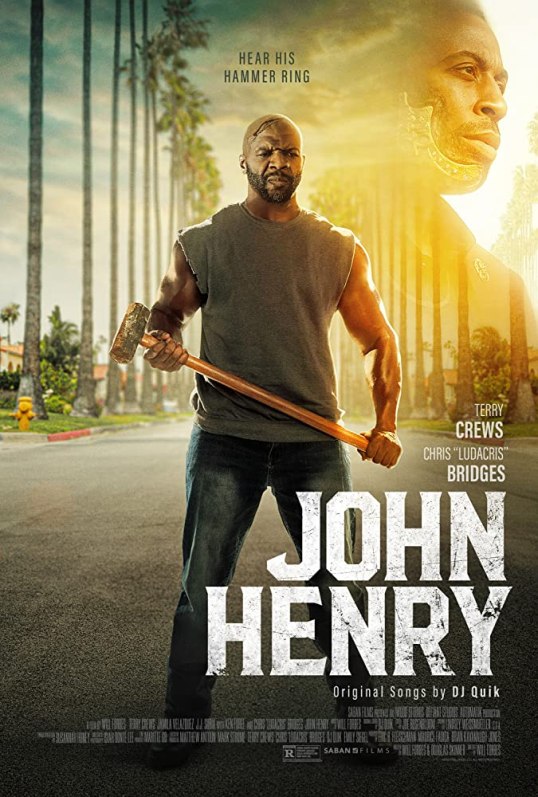

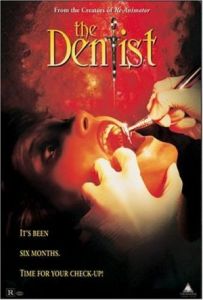

Michael (William Bumiller) owns the hottest health club in Los Angeles but that may not stay true if he can’t do something about all the guests dying. Members get baked alive in the sauna. Another is killed when a malfunctioning workout machine pulls back his arms and causes a rib to burst out of one side of his body. Shower tiles fly off the wall and panic a bunch of naked women. A woman loses her arm in a blender and a man is somehow killed by a frozen fish. Strangely, all of the deaths don’t seem to hurt business as people still keep coming to the gym. Surely, there are other, safer health clubs in Los Angeles. Alan (Corbin Bernsen) may be a wealthy dentist in Malibu but he still has problems. He has got an IRS agent (Earl Boen) breathing down his neck. His assistant, Jessica (Molly Hagan), has no respect for him. His demanding patients don’t take care of their teeth. His wife (Linda Hoffman) is fucking the pool guy (Michael Stadvec). When Alan feels up a beauty queen while she’s passed out from the nitrous oxide, her manager (Mark “yes, the Hulk” Ruffalo) punches him and then goes to the police. Under pressure from all sides, Alan loses his mind and a crazy dentist with a drill means a lot of missing teeth.

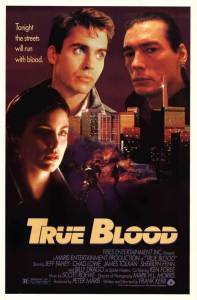

Alan (Corbin Bernsen) may be a wealthy dentist in Malibu but he still has problems. He has got an IRS agent (Earl Boen) breathing down his neck. His assistant, Jessica (Molly Hagan), has no respect for him. His demanding patients don’t take care of their teeth. His wife (Linda Hoffman) is fucking the pool guy (Michael Stadvec). When Alan feels up a beauty queen while she’s passed out from the nitrous oxide, her manager (Mark “yes, the Hulk” Ruffalo) punches him and then goes to the police. Under pressure from all sides, Alan loses his mind and a crazy dentist with a drill means a lot of missing teeth. Ten years after being wrongly accused of murdering a cop, Raymond Trueblood (Jeff Fahey) returns to the old neighborhood. Ray has just finished a stint with the Marines and he is no longer the irresponsible hoodlum that he once was. He wants to rescue his younger brother, Donny (Chad Lowe), from making the same mistakes that he made. But Donny now hates Ray and is running with Ray’s former friend, Spider Masters (Billy Drago). Spider is also responsible for framing Ray for killing the cop. When he is not trying to save his brother, Ray falls in love with Jennifer Scott (Sherilyn Fenn), a tough waitress who is soon being menaced by Spider.

Ten years after being wrongly accused of murdering a cop, Raymond Trueblood (Jeff Fahey) returns to the old neighborhood. Ray has just finished a stint with the Marines and he is no longer the irresponsible hoodlum that he once was. He wants to rescue his younger brother, Donny (Chad Lowe), from making the same mistakes that he made. But Donny now hates Ray and is running with Ray’s former friend, Spider Masters (Billy Drago). Spider is also responsible for framing Ray for killing the cop. When he is not trying to save his brother, Ray falls in love with Jennifer Scott (Sherilyn Fenn), a tough waitress who is soon being menaced by Spider.