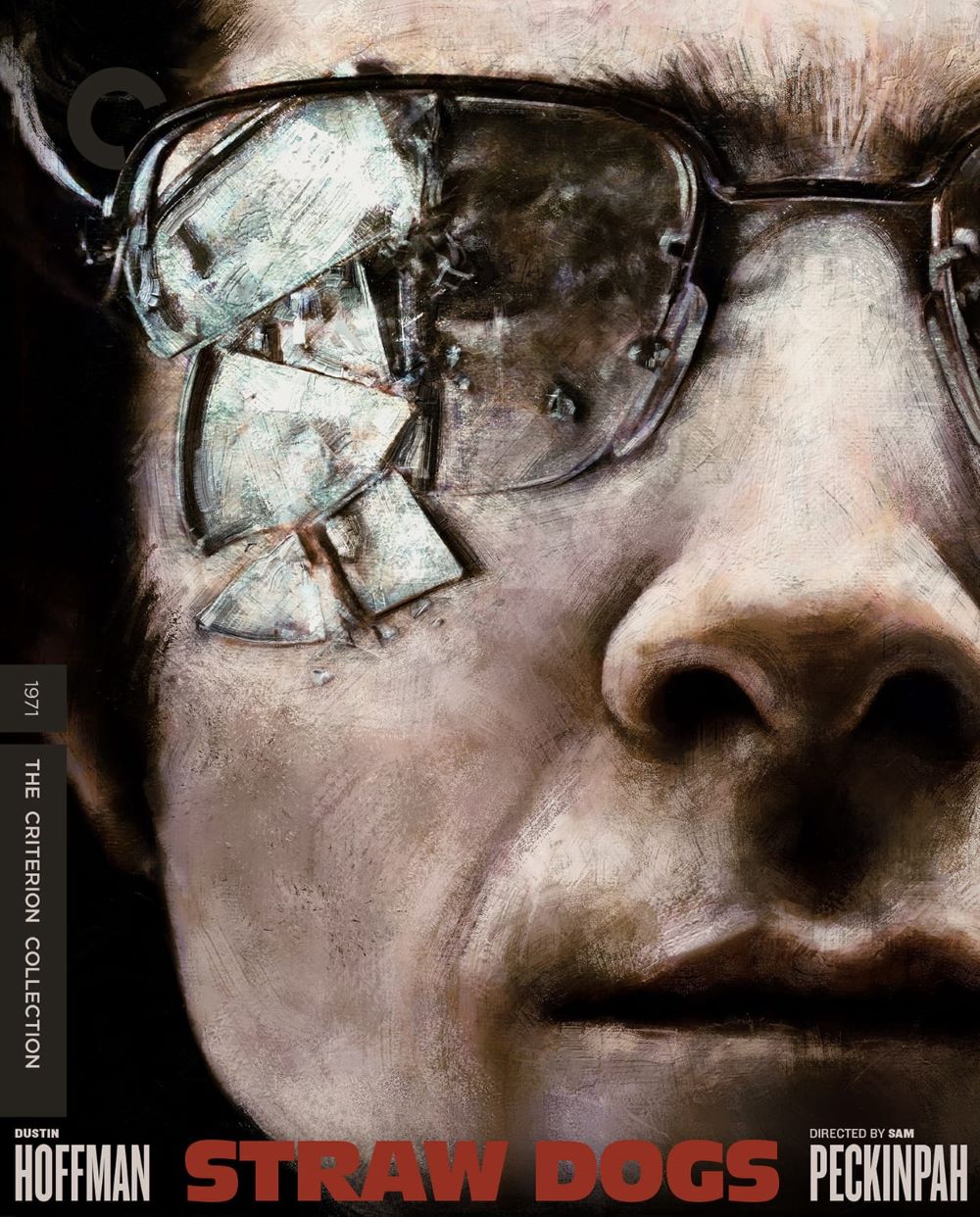

“Violence can be the only answer sometimes.” — David Sumner

Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs is a raw, compelling dive into the breakdown of civility and the primal instincts bubbling underneath. The story follows David Sumner, a mild-mannered American mathematician, who moves with his wife Amy to her rural English hometown. The couple’s plan for a quiet life takes a sharp turn when tensions with the locals spiral out of control, resulting in a violent showdown. At its core, the film examines how far a person can be pushed before the veneer of civilization peels away, revealing something much wilder underneath.

The tension starts subtly, as David’s intellectual and pacifist nature clashes with the rough, territorial mindset of the local men. This brewing conflict isn’t just about cultural difference but taps into deeper themes around masculinity, power, and identity. Straw Dogs asks difficult questions about what it means to be a man, exploring how fragile male identity can be when confronted with real or perceived threats. David’s journey is less about heroism and more about the psychological and emotional transformation forced upon a man who initially seems ill-equipped for the violence unleashed around him. The whole film operates as a kind of symbolic stage where primal instincts and societal expectations collide, forcing each character to confront their own limits.

Amy’s role in the film is both pivotal and deeply complex. Her experience of assault, handled with subtle but unflinching attention, adds emotional and thematic weight without dominating the narrative. The film portrays her trauma through its impact on her and the shifting dynamics in her relationship with David, inviting reflection on resilience and struggle for control. Amy is depicted not merely as a victim but as a layered character navigating vulnerability and strength amid the hostile environment. This approach challenges viewers to consider the nuanced and often contradictory responses to trauma, avoiding simplistic victim narratives while emphasizing its profound consequences.

The rural setting of Straw Dogs is more than just a backdrop; it becomes a character in its own right. The close-knit, insular community embodies a microcosm where social order teeters and violence hides just beneath the surface. Law enforcement and authority figures seem ineffective or indifferent, which heightens the sense of isolation and lawlessness. The hostility from some village locals, including Amy’s ex-boyfriend Charlie, feeds into a toxic masculinity that sees David as weak and out of place. Peckinpah carefully stages this clash, using tension and silence as expertly as physical violence, making viewers feel the pressure ramping up until it finally snaps.

Dustin Hoffman’s portrayal of David is quietly brilliant in its subtlety. He plays David as a man trapped between worlds—intellectual and physical, passivity and aggression—with a restrained but deeply affecting performance. Hoffman’s ability to convey complex emotions beneath a calm exterior makes David’s eventual transformation all the more gripping. Susan George delivers an equally powerful performance as Amy, capturing the mixture of fear, defiance, and heartbreak her character endures. Their dynamic feels authentic and layered, making the viewer invested in their peril. The supporting cast, including actors like Peter Vaughan, add a layer of authentic menace, embodying the grim rural antagonists with convincing grit and intensity. The performances overall ground the film’s explosive themes in believable, relatable humans.

Themes in Straw Dogs extend beyond just personal violence to address ideas about identity and societal breakdown. The film explores the notion of the “symbolic order”—how individuals fit into and negotiate the rules and roles imposed by society. David’s identity crisis and his uneasy place within the village spotlight questions of power, emasculation, and rebirth. Peckinpah uses psycho-sexual imagery—such as symbols of emasculation and phallic power—to deepen the psychological stakes of David’s journey. The film conveys how deeply fragile human identity is and how violence can act as a brutal yet transformative force pushing individuals to redefine themselves. At the same time, the portrayal of Amy complicates these themes by challenging traditional gender roles, making the film as much about female agency as male dominance.

The film’s violence is famously brutal and unsettling. Peckinpah does not shy away from showing the full consequences of escalating conflict, culminating in an intense and chaotic finale where the line between victim and aggressor blurs. This isn’t violence for spectacle but a narrative and thematic necessity that Peckinpah uses to strip away pretenses and reveal the raw human instincts beneath. It’s this uncompromising depiction that both shocked audiences at the time and continues to provoke discussion about the nature of power and survival. The film is also notable for its innovative editing, with Peckinpah’s use of jump cuts and slow-motion heightening the emotional intensity and pacing the violence with a rhythmic, almost visceral punch.

Ultimately, Straw Dogs is a challenging film that forces viewers to confront disturbing truths about human nature, relationships, and societal order. Its exploration of violence and masculinity is complex and often uncomfortable, presenting no easy answers. The film remains a significant piece of cinema for its bold themes, outstanding performances, and the way it captures the frailty and ferocity of its characters. Peckinpah’s direction melds tension, psychological drama, and physical action into a gripping, unforgettable experience. Though controversial for its content, Straw Dogs endures as a powerful work that asks what truly happens when the thin line between civilization and savagery breaks down.

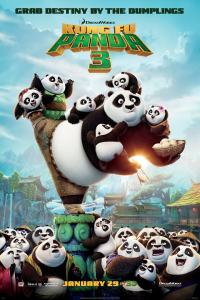

Having become the Dragon Warrior and the Champion of the Valley of Peace on many occasions, Po (Jack Black) has reached a point where its time for him to train others. All of this becomes complicated when Kai (J.K. Simmons), a former enemy of Master Oogway (Randall Duk Kim) returns to the Valley to capture the Chi of the new Dragon Warrior and anyone else that stands in his way.

Having become the Dragon Warrior and the Champion of the Valley of Peace on many occasions, Po (Jack Black) has reached a point where its time for him to train others. All of this becomes complicated when Kai (J.K. Simmons), a former enemy of Master Oogway (Randall Duk Kim) returns to the Valley to capture the Chi of the new Dragon Warrior and anyone else that stands in his way.