“Tommy, can you hear me?”

That’s a question that’s asked frequently in the 1975 film, Tommy. An adaptation of the famous rock opera by the Who (though Pete Townshend apparently felt that the film’s vision was more director Ken Russell’s than anything that he had meant to say), Tommy tells the story of a “deaf, dumb, and blind kid” who grows up to play a mean pinball and then become a cult leader. Why pinball? Who knows? Townshend’s the one who wrote Pinball Wizard but Ken Russell is the one who decided to have Elton John sing it while wearing giant platform shoes.

Tommy opens, like so many British films of the 70s, with the blitz. With London in ruins, Captain Walker (the almost beatifically handsome Robert Powell) leaves his wife behind as he fights for his country. When Walker is believed to be dead, Nora (Ann-Margaret) takes Tommy to a holiday camp run by Frank (Oliver Reed). Oliver Reed might not be the first person you would expect to see in a musical and it is true that he wasn’t much of a singer. However, it’s also true that he was Oliver Reed and, as such, he was impossible to look away from. Even his tuneless warbling is somehow charmingly dangerous. Nora falls for Frank but — uh oh! — Captain Walker’s not dead. When the scarred captain surprises Frank in bed with Nora, Frank hits him over the head and kills him. Young Tommy witnesses the crime and is told that he didn’t see anything and he didn’t hear anything and that he’s not going to say anything.

And so, as played by Roger Daltrey, Tommy grows up to be “deaf, dumb, and blind.” Various cures — from drugs to religion to therapy — are pursued to no avail. As the Acid Queen, Tina Turner sings and dances as if she’s stealing Tommy’s soul. As the Therapist, Jack Nicholson is all smarmy charm as he gently croons to Ann-Margaret. Eric Clapton performs in front of a statue of Marilyn Monroe. Ann-Margaret dances in a pool of beans and chocolate and rides a phallic shaped pillow. As for Tommy, he eventually becomes the Pinball Wizard and also a new age messiah. But it turns out that his new followers are just as destructive as the people who exploited him when he was younger. It’s very much a Ken Russell film, full of imagery that is shocking and occasionally campy but always memorable.

I love Tommy. It’s just so over-the-top and absurd that there’s no way you can ignore it. Ann-Margaret sings and dances as if the fate of the world depends upon it while Oliver Reed drinks and glowers with the type of dangerous charisma that makes it clear why he was apparently seriously considered as Sean Connery’s replacement in the roles of James Bond. As every scene is surreal and every line of dialogue is sung, it’s probably easy to read too much into the film. It could very well be Ken Russell’s commentary on the New Age movement and the dangers of false messiahs. It could also just be that Ken Russell enjoyed confusing people and 1975 was a year when directors could still get away with doing that. With each subsequent viewing of Tommy, I become more convinced that some of the film’s most enigmatic moments are just Russell having a bit of fun. The scenes of Tommy running underwater are so crudely put together that you can’t help but feel that Russell was having a laugh at the expense of people looking for some sort of deeper meaning in Tommy’s journey. In the end, Tommy is a true masterpiece of pop art, an explosion of style and mystery.

Tommy may seem like a strange film for me to review in October. It’s not a horror film, though it does contain elements of the genre, from the scarred face of the returned to Captain Walker to the Acid Queen sequence to a memorable side story that features a singer who looks like a junior Frankenstein. To me, though, Tommy is a great Halloween film. Halloween is about costumes and Tommy is ultimately about the costumes that people wear and the personas that they assume as they go through their lives. Oliver Reed goes from wearing the polo shirt of a holiday camp owner to the monocle of a tycoon to the drab jumpsuits of a communist cult leader. Ann-Margaret’s wardrobe is literally a character of its own. Everyone in the film is looking for meaning and identity and the ultimate message (if there is one) appears to be that the search never ends.

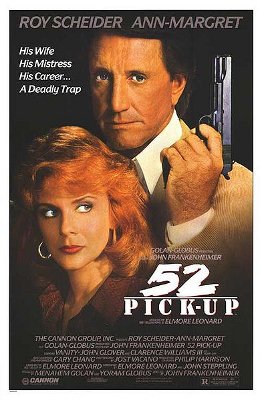

Harry Mitchell (Roy Scheider) is a businessman who has money, a beautiful wife named Barbara (Ann-Margaret), a sexy mistress named Cini (Kelly Preston), and a shitload of trouble. He is approached by Alan Raimey (John Glover) and informed that there is a sex tape of him and his mistress. Alan demands $105,000 to destroy the tape. When Harry refuses to pay, Alan and his partners (Clarence Williams III and Robert Trebor) show up with a new tape, this one framing Harry for the murder of Cini. They also make a new demand: $105,000 a year or else they will release the tape. Can Harry beat Alan at his own game without harming his wife’s political ambitions?

Harry Mitchell (Roy Scheider) is a businessman who has money, a beautiful wife named Barbara (Ann-Margaret), a sexy mistress named Cini (Kelly Preston), and a shitload of trouble. He is approached by Alan Raimey (John Glover) and informed that there is a sex tape of him and his mistress. Alan demands $105,000 to destroy the tape. When Harry refuses to pay, Alan and his partners (Clarence Williams III and Robert Trebor) show up with a new tape, this one framing Harry for the murder of Cini. They also make a new demand: $105,000 a year or else they will release the tape. Can Harry beat Alan at his own game without harming his wife’s political ambitions?