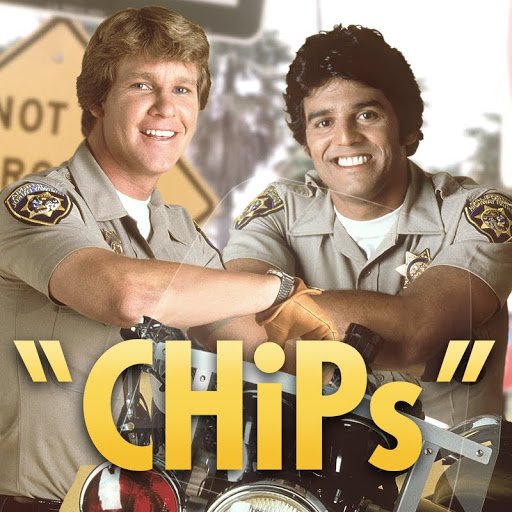

Welcome to Late Night Retro Television Reviews, a feature where we review some of our favorite and least favorite shows of the past! On Mondays, I will be reviewing CHiPs, which ran on NBC from 1977 to 1983. The entire show is currently streaming on Prime!

This week, it’s Ponch and Jon’s anniverary!

Episode 5.3 “Moonlight”

(Dir by Earl Bellamy, originally aired on October 18th, 1981)

A highway accident leads to a bunch of cars flying through the air in slow motion!

Ponch works off-duty as a security guard for an action film. Ponch being Ponch, he ends up flirting with the two female stars. He also ends up accidentally flirting with their stunt doubles, both of whom turn out to be men wearing blonde wigs. Oh, Ponch!

Someone is dumping toxic waste and ruining the beautiful California country side. Ponch and Jon turn to their old friend, trucker Robbie Davis (Katherine Cannon), for help. However, it turns out that the waste is being transported and dumped by someone close to Robbie!

There’s a lot going on in this episode but the majority of the screentime is taken up with Getraer, Grossman, Baricza, Turner, and Bonnie thinking about how to celebrate Ponch and Jon’s 4th anniversary as partners. At one point, Getraer does point out that it’s unusual for an entire department to celebrate the anniversary of a partnership. I’m glad that someone said that because, seriously, don’t these people have a job to do? I mean, aren’t they supposed to be out there, issuing tickets and preventing crashes like the one that opened this episode? You’re not getting paid to be party planners, people!

Knowing just how much Larry Wilcox and Erik Estrada disliked each other when the cameras weren’t rolling, it’s hard not to feel as if there’s a bit of wish-fulfillment going on with the anniversary storyline. Watching everyone talk about how Jon and Ponch are the perfect team, one gets the feeling that the show itself is telling its stars, “Can you two just get along? Everyone loves you two together!”

Reportedly, by the time the fifth season rolled around, Wilcox was frustrated with always having to play second fiddle to Estrada. Having binged the show, I can understand the source of his frustration. During the first two seasons, Wilcox and Estrada were given roughly the same amount of screen time in each episode. In fact, Estrada often provided the comic relief while Wilcox did the serious police work. But, as the series progressed, the balance changed and it soon became The Ponch Show. If there was a beautiful guest star, her character would fall for Ponch. If there was a rescue to be conducted, Ponch would be the one who pulled it off. When it came time to do something exciting to show off the California lifestyle, one can b sure that Ponch would be the one who got to do it. Baker got pushed to the side. This episode, however, allows Baker to rescue someone while Ponch watches from the background. “See, Larry?” the show seems to be saying, “We let you do things!”

As for the episode itself, it’s okay. There’s enough stunts and car accidents to keep the viewers happy. That said, the toxic dump storyline plays out way too slowly. At one point, Baricza finds a bunch of barrels off the side of the road and he looks like he’s about to start crying. It’s an odd moment.

The episode ends with Baker and Ponch happy. It wouldn’t last. This would be Larry Wilcox’s final season as a member of the Highway Patrol.