Mardi Gras in New Orleans has always been a legendary party.

If you doubt me on this, just watch the 1930 film, Dixiana. Dixiana is all about Mardi Gras. I mean, there is a plot of sorts but it’s pretty easy to guess that, for audiences in 1930, the promise of a spectacular Madi Gras finale (filmed in technicolor, I might add) was the main appeal of this film. Dixiana itself takes place in the 1840s so there you have it. 90 years ago, RKO Pictures made a lavish movie about a Mardi Gras celebration that had happened nearly 100 years earlier. That’s quite a legendary party, no?

As with many pre-Code films about the Antebellum South, it can be a bit awkward to watch Dixiana today. This is a film that opens on a plantation, with Cornelius Van Horn (Joseph Cawthorn) and his son, Carl (Everett Marshall), discussing how much they enjoy listening to the slaves sing about the Mississippi River. They’re amazed that the slaves can sing so beautifully about water. (It doesn’t occur to them that the song was actually about going up the river and finding freedom.) Cornelius and Carl, we discover, are actually from Pennsylvania. Cornelius has recently remarried, to the snobbish Birdie (Jobnya Howland) and both he and his son have only recently moved down to her native Louisiana. Carl and Cornelius are still getting used to life in and the customs of the South. Cornelius, for instance, explains that he regularly frees some of his slaves and he imagines that’s why they’re always so happy. But if he really wants them all to be happy why doesn’t he just free them all and maybe stop buying slaves all together? Let’s just say that Dixiana is not the film to watch if you’re looking for an honest look at American life before the Civil War.

Anyway, if you’re still interested in seeing the film after reading all of that, the majority of Dixiana takes place in New Orleans. Carl goes into town, does some gambling, and sees a show. He is immediately smitten with a performer named Dixiana (Bebe Daniels) and he asks her to marry him. Even though her two best friends, Peewee and Ginger (played by the comedy team of Wheeler and Woolsey), are weary, Dixiana accepts his proposal. Carl takes Dixiana back to the plantation with him. Unfortunately, he also takes Peewee and Ginger and they soon let slip that they’re all circus performers. Birdie is scandalized. There’s no way her stepson is going to bring shame on the family by marrying a circus performer!

So, Dixiana and her friends head back to New Orleans. The circus no longer wants her so Dixiana is forced to work in a gambling hall that’s owned by smarmy Royal Montague (Ralf Harolde). Montague has his own personal interest in Dixiana but she’s still in love with Carl. So, Royal plots to not only have Dixiana crowned as the Queen of Mardi Gras but also to trick Carl into accept a duel with him. Montague, of course, plans to pull an Aaron Burr and cheat. Meanwhile, Peewee and Ginger steal money, kick each other in the backside, and fight a duel of their own….

And really, none of that matters. In the end, the film’s storyline is mostly just busywork. The main reason that anyone would want to see this film is for the final 20 minutes, which is when the grainy black-and-white cinematography is replaced by gloriously vibrant technicolor and the Mardi Gras celebrations begin. There’s singing. There’s dancing. There’s even Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, making his film debut and dancing up a storm. Seriously, 1840s Mardi Gras looked like it would have been fun to attend, even if it does sometimes seem more like a lively cotillion as opposed to the orgy of alcohol poisoning that everyone knows and loves today.

Dixiana is one of those films that’s fallen into the public domain and, as such, it tends to turn up in a lot of cheap DVD boxsets. There’s quite a few prints out that are completely in black-and-white and which don’t feature the sudden change to color. That’s a shame because, whatever flaws this film may have, it does make good use of that technicolor during the final 20 minutes. It’s big and lavish and gorgeous to look at and it’s easy to imagine the valuable escape that it provided for audiences at the start of the Depression.

Today, Dixiana is probably most interesting as a historical document. It’s not quite as racy as one might expect from a pre-code film but it’s a good example of the type of lavish musicals that were popular among audiences who, in the 30s, used the film as a way to escape from the grimness of reality. And, if nothing else, it’s proof that Mardi Gras in New Orleans has always been a big deal.

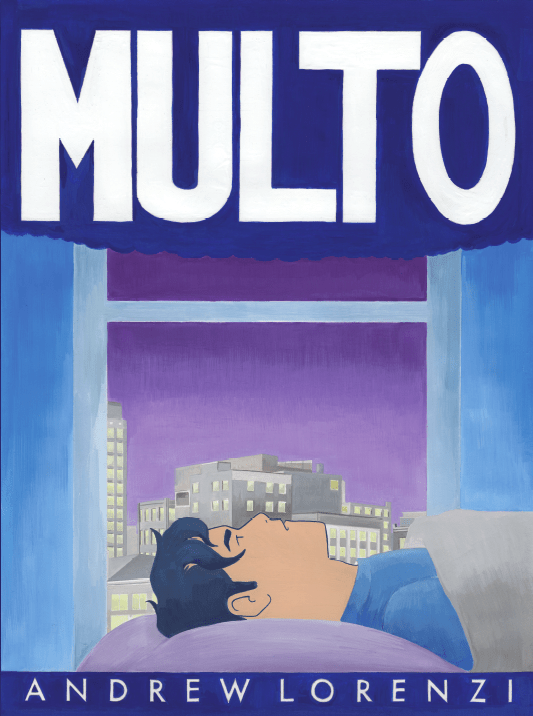

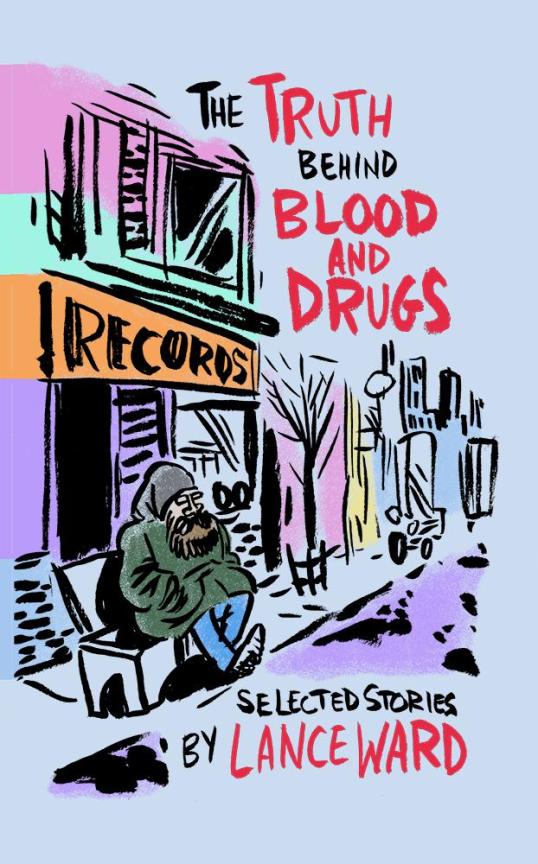

Ryan C.'s Four Color Apocalypse