Brad listed his top Bronson films so I guess I should list mine! Below are my six favorite Bronson films. (Why 6? Because Lisa doesn’t do odd numbers!)

Now, to make clear, I’m not the Bronson expert that Brad is so I will picking from a smaller pool of selections. But no matter! Let’s do this!

6. Death Wish III (1985, dir by Michael Winner)

Yes, I have to start with Death Wish III. The Death Wish sequels are definitely a mixed bag but Death Wish III was wonderfully over-the-top, a film that cheerfully dropped Bronson in the middle of an absurd circus and allowed him to tame the lions, as it were. I will always love this film for the presence of Plunger Guy, a bad guy who heads into battle carrying a plunger.

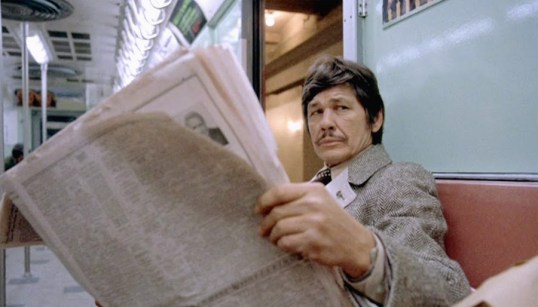

5. Breakheart Pass (1975, dir by Tom Gries)

This is an enjoyable mix of a western, a murder mystery, and an adventure film. Charles Bronson is a mysterious man on a snowbound train. Charles Durning, Ben Johnson, Richard Crenna, Jill Ireland, and Ed Lauter co-star and everyone — especially Johnson and Durning — bring a lot to their roles. This may not be one of Bronson’s best-known films but it is one of his most enjoyable and Bronson himself is at his most likable.

4. Death Wish (1973, dir by Michael Winner)

“My heart bleeds a little for the less fortunate,” Bronson’s Paul Kersey says at the start of the film and those of us watching immediately say, “C’mon, Charlie, really?” That said, one reason why Death Wish works as well as it does is because Bronson actually gives a very good and very emotionally honest performance as a man who finally snaps and starts to take the law into his own hands. (I love the barely veiled contempt that’s present whenever Paul talks to his son-in-law.) Not surprisingly, considering that it was directed by Michael Winner, Death Wish is an often-sordid film that doesn’t have a hint of subtlety. But it’s also brutally effective, a film that captures the way a lot of people feel when they hear about reports of out-of-control crime. Even today, it’s easy to see why Death Wish was the film that finally Bronson a star in the United States.

3. Once Upon A Time In The West (1968, dir by Sergio Leone)

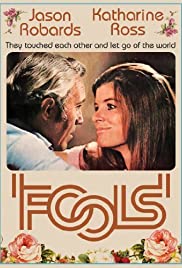

Bronson plays Harmonica in the most epic of all of Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns. Leone pays homage to the American western while also gleefully subverting it. The quiet and unemotional Bronson is the film’s hero. Henry Fonda is the sadistic villain who guns down a child. Jason Robards is an outlaw. While I don’t consider it to be quite as good as either The Good, The Bad, or the Ugly or Once Upon A Time In America, Once Upon A Time In The West is still one of Leone’s masterpieces.

2. From Noon Till Three (1976, dir by Frank D. Gliroy)

For all of his reputation for being a tough guy who didn’t show much emotion, there was no denying Bronson’s love for his second wife, Jill Ireland. From Noon Till Three brings Bronson and Ireland together in a film that is a third western, a third romantic comedy, and a third social satire. It’s a film that gives Bronson a chance to show off his romantic side and it might leave you surprised! The film also featured Jill Ireland’s best performance in a Bronson film. I always highly recommend this one. It’s proof that there was more to Bronson than just shooting the bad guys.

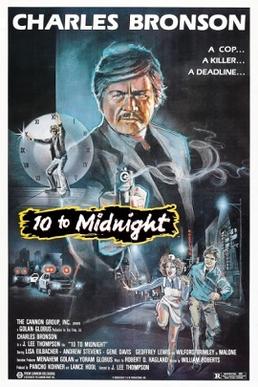

- Ten To Midnight (1983, dir by J. Lee Thompson)

This is the ultimate 80s Bronson film and one that I like for a reason that might surprise you. On the one hand, you’ve got Bronson as a tough cop, Andrew Stevens as his liberal partner, and Gene Davis as the disturbingly plausible serial killer, Warren Stacy. Bronson is great as the world weary cop. His scenes with Stevens are amusing and, at times, even poignant. (It helps that Stevens was the rare co-star that Bronson liked.) Davis is terrifying and the film’s final moments are very emotionally satisfying. (“No, we won’t.”) But the reason why I love this film is because of the relationship between Bronson’s cop and his daughter, who played by Lisa Eilbacher. Their scenes together — testy but loving — are well-acted by both actors and they always make me think of me and my Dad. Ten To Midnight is the Bronson film that actually makes me cry.

California. The 1870s. Sheriff Pearce (Ben Johnson) boards a train with his prisoner, an alleged outlaw named John Deakin (Charles Bronson). The train is mostly full of soldiers, under the command of Major Claremont (Ed Lauter), who are on their way to Fort Humboldt. The fort has suffered a diphtheria epidemic and the soldiers are supposedly transporting medical supplies.

California. The 1870s. Sheriff Pearce (Ben Johnson) boards a train with his prisoner, an alleged outlaw named John Deakin (Charles Bronson). The train is mostly full of soldiers, under the command of Major Claremont (Ed Lauter), who are on their way to Fort Humboldt. The fort has suffered a diphtheria epidemic and the soldiers are supposedly transporting medical supplies.

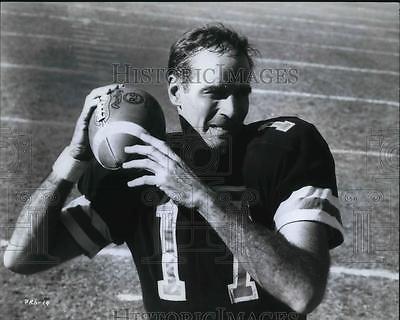

Quarterback Cat Catlan (Charlton Heston) used to be one of the greats. For fifteen years, he has been a professional football player. He probably should have retired after he led the New Orleans Saints to their first championship but, instead, the stubborn Cat kept playing. Now, he is 40 years old and struggling to keep up with the younger players. His coach (John Randolph) says that Cat has another two or three years left in him but the team doctor (G.D. Spradlin who, ten years later, played a coach in North Dallas Forty) says that one more strong hit could not only end Cat’s career but possibly his life as well. Two of former Cat’s former teammates (Bruce Dern and Bobby Troup) offer to help Cat find a job off the field but Cat tells them the same thing that he tells his long-suffering wife (Jessica Walter). He just has to win one more championship.

Quarterback Cat Catlan (Charlton Heston) used to be one of the greats. For fifteen years, he has been a professional football player. He probably should have retired after he led the New Orleans Saints to their first championship but, instead, the stubborn Cat kept playing. Now, he is 40 years old and struggling to keep up with the younger players. His coach (John Randolph) says that Cat has another two or three years left in him but the team doctor (G.D. Spradlin who, ten years later, played a coach in North Dallas Forty) says that one more strong hit could not only end Cat’s career but possibly his life as well. Two of former Cat’s former teammates (Bruce Dern and Bobby Troup) offer to help Cat find a job off the field but Cat tells them the same thing that he tells his long-suffering wife (Jessica Walter). He just has to win one more championship.