Though the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences claim that the Oscars honor the best of the year, we all know that there are always worthy films and performances that end up getting overlooked. Sometimes, it’s because the competition too fierce. Sometimes, it’s because the film itself was too controversial. Often, it’s just a case of a film’s quality not being fully recognized until years after its initial released. This series of reviews takes a look at the films and performances that should have been nominated but were, for whatever reason, overlooked. These are the Unnominated.

Elliott Gould is Phillip Marlowe!

If I had to pick one sentence to describe the plot of 1973’s The Long Goodbye, that would be it. Robert Altman’s adaptation of the Raymond Chandler detective novel loosely follows Chandler’s original plot, though Altman did definitely make a few important changes. Altman moved the story from the 50s to the then-modern 70s, replacing Chandler’s hard-boiled Los Angeles with a satirical portrait of a self-obsessed California, populated by gurus and hippies. And Altman did change the ending of the book, taking what one could argue is a firmer stand than Chandler did in the novel. In the end, though, the film really is about the idea of Chandler’s tough detective being reimagined as Elliott Gould.

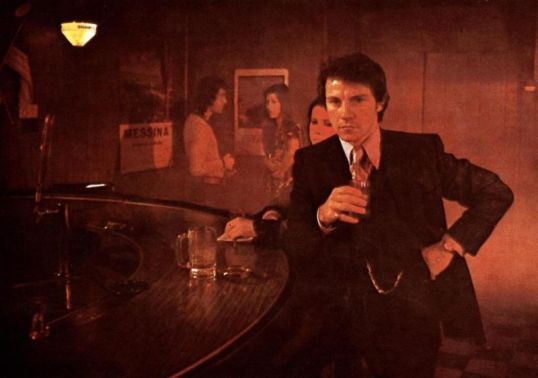

Rumpled, mumbling, and with a permanent five o’clock shadow, Gould plays Marlowe as being an outsider. He lives in a shabby apartment. His only companion is a cat who randomly abandons him (as cats tend to do). With his wardrobe that seems to consist of only one dark suit, Marlowe seems out-of-place in the California of the 70s. When Marlowe’s friend, Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton), asks Marlowe to drive him to Mexico, one gets the feeling that Lennox isn’t just asking because Marlowe’s a friend. He’s asking because he suspects Marlowe would never be a good enough detective to figure out what he’s actually doing.

After Terry’s wife is murdered, Marlowe is informed that 1) Terry has committed suicide and 2) Marlowe is now a suspect. Convinced that Terry would have never killed himself, Marlowe investigates on his own. He meets Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell), a gangster who demands that Marlowe recover some money that he claims Terry stole. Marty seems like an almost reasonable criminal until he smashes a coke bottle across his girlfriend’s face. (One of Marty’s bodyguards is played by a silent Arnold Schwarzenegger.) Meanwhile, Terry’s neighbors include an alcoholic writer named Roger Wade (Sterling Hayden) and his wife, Eileen (Nina van Pallandt). Like Marlowe, Roger is a man out-of-time, a Hemingwayesque writer who has found himself in a world that he is not capable of understanding. Henry Gibson, who would later memorably play Haven Hamilton in Altman’s Nashville, appears as Wade’s “doctor.”

Marlowe, with his shabby suits and a cigarette perpetually dangling from his mouth, gets next to no respect throughout the film. No one takes him seriously but Marlowe proves himself to be far more clever than anyone realizes. Elliott Gould gives one of his best performances as Marlowe, playing him as a man whose befuddled exterior hides a clear sense of right and wrong. Gould convinces us that Marlowe is a man who can solve the most complex of mysteries, even if he can’t figure out where his cat goes to in the middle of the night. His code makes him a hero but it also makes him an outsider in what was then the modern world. The film asks if there’s still a place for a man like Phillip Marlowe in a changing world and it leaves it to us to determine the answer.

Frequently funny but ultimately very serious, The Long Goodbye is one of the best detective films ever made. Just as Altman did with McCabe & Mrs. Miller, he uses the past to comment on what was then the present. And, just as with McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye is a film that was initially released to mixed reviews, though it would later be acclaimed by future viewers and critics. Whereas McCabe & Mrs. Miller received an Oscar nomination for Julie Christie’s performance as Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye was thoroughly snubbed by the Academy. Altman, Gould, Hayden, and the film itself were all worthy of consideration but none received a nomination. Instead, that year, the Oscar for Best Picture went to The Sting, a far less cynical homage to the crime films of the past.

Previous entries in The Unnominated: