HARD TIMES is probably the best movie that features Charles Bronson in the lead, and it’s my personal favorite movie of all time as of the date of this review. I reserve the right to change this opinion at any time!

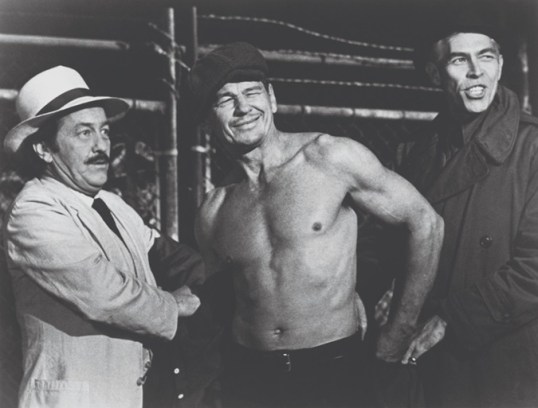

Charles Bronson is Chaney, a drifter who’s riding the rails in the south during the great depression. Soon after getting off the train in some unnamed southern town, Chaney comes across an underground “fight” where we first meet Speed, played by the great James Coburn. It seems Speed is the money man for this big lug of a fighter who gets his butt kicked in front of God, the local underground fighting world, a man with horrible teeth, and Chaney. After witnessing this fiasco, Chaney follows Speed to a local restaurant where he apparently waits in the shadows until Speed goes up to the counter to get a refill of oysters and a couple of lemons. I say this because when Speed turns from the counter with his newly filled tray, Chaney is sitting at Speed’s table. I’m surprised that Speed even talks to him because the first thing Chaney does is help himself to an oyster, WITHOUT EVEN ASKING! Even with this breach of etiquette, Speed discusses the fight from earlier in the evening with Chaney, who offers his fighting services to Speed since the “big lug” is clearly not a good investment into the future and who is probably in a hospital overnight dealing with a concussion. Speed is hesitant to accept this offer since Chaney appears to be fairly old (Bronson was 53 when he made the film), but he changes his mind when Chaney offers his last $6 bucks to Speed to bet on him. Cut to Chaney getting his chance to fight. This is a fun scene because his opponent is the same fighter from earlier who kicked the big lug’s butt. The guy even taunts Chaney for being too old. The fight starts and it consists of two hits, Chaney hits the smartass, the smartass hits the ground. Somewhat amazed, Speed takes Chaney to New Orleans, and the two embark on an odyssey together to win fights and make thick wads of cash. The remainder of the film documents that odyssey, although it does take time out for a few “in-betweens.”

HARD TIMES is one of Bronson’s best films, and one of the main reasons why is that it provides a boatload of audience satisfaction. There are many examples of this. First is the scene mentioned above where Chaney takes out the smirking, dismissive fighter who sees our hero as too old. Too old my ass! In another scene, a bunch of unrefined Cajuns out in the boondocks refuse to pay up after Chaney kicks their fighter’s butt. Rather than pay up, the slimy Cajuns pull out a gun and dare Speed and Chaney to come take the money. Our heroes leave at that time, but Chaney convinces them to hang around out in the country for awhile so they can surprise the Cajuns under the cover of darkness at the local honkytonk, which happens to be owned by the head slimy Cajun. Chaney takes the gun, takes the money, and then shoots up the place with the gun, grinning as he saves the last bullet to shoot a mirror he’s looking directly into. It’s a fun scene that ends with Chaney, Speed and the gang speeding off into the night laughing like hyenas! In another scene, Chaney takes on the big, bald-headed, unbeatable fighter Jim Henry (Robert Tessier) in an awesome cage match. Let’s just say Jim Henry thought he was unbeatable and leave it at that. And finally, a competing New Orleans money man (Jim Henry’s guy) just can’t stand that he no longer has the top fighter in town, so he brings in a fighter from Chicago to take on Chaney. I won’t tell you what happens, but it’s some really fun stuff!

The cast of HARD TIMES also elevates the film to top tier status. I’ve already discussed Bronson and Coburn, but Strother Martin and Jill Ireland also add to the joy. Martin plays Poe, Chaney’s drug addict cut man, who dresses up like he could grow up to be Colonel Sanders in his older age. It’s a fun performance that adds a lot to the film. Jill Ireland plays Chaney’s love interest. She’s quite beautiful, but she seems to always be giving Chaney a hard time about what he does for a living. His response is usually to simply leave when she starts that BS. I thinks that’s kind of fun too.

And finally, this was the directorial debut of Walter Hill, the man behind THE WARRIORS, THE DRIVER, THE LONG RIDERS, SOUTHERN COMFORT, 48 HOURS, and RED HEAT. His movie is lean and mean, without a wasted moment that isn’t moving the film along. Hill has crafted a fun movie, filled with great performances. I think it’s one of the most underrated films of the 1970’s!

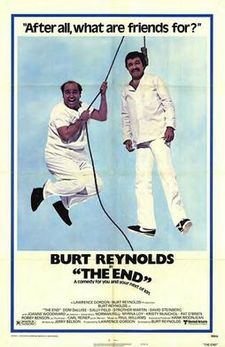

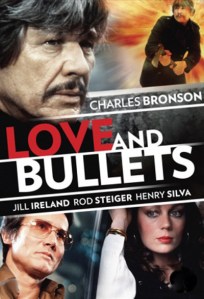

Joe Bomposa (Rod Steiger) may wear oversized glasses, speak with a stutter, and spend his time watching old romantic movies but don’t mistake him for being one of the good guys. Bomposa is a ruthless mobster who has destroyed communities by pumping them full of drugs. Charlie Congers (Charles Bronson) is a tough cop who is determined to take Bomposa down. When the FBI learns that Bomposa has sent his girlfriend, Jackie Pruit (Jill Ireland), to Switzerland, they assume that Jackie must have information that Bomposa doesn’t want them to discover. They send Congers over to Europe to bring her back. Congers discovers that Jackie does not have any useful information but Bomposa decides that he wants her dead anyway.

Joe Bomposa (Rod Steiger) may wear oversized glasses, speak with a stutter, and spend his time watching old romantic movies but don’t mistake him for being one of the good guys. Bomposa is a ruthless mobster who has destroyed communities by pumping them full of drugs. Charlie Congers (Charles Bronson) is a tough cop who is determined to take Bomposa down. When the FBI learns that Bomposa has sent his girlfriend, Jackie Pruit (Jill Ireland), to Switzerland, they assume that Jackie must have information that Bomposa doesn’t want them to discover. They send Congers over to Europe to bring her back. Congers discovers that Jackie does not have any useful information but Bomposa decides that he wants her dead anyway.

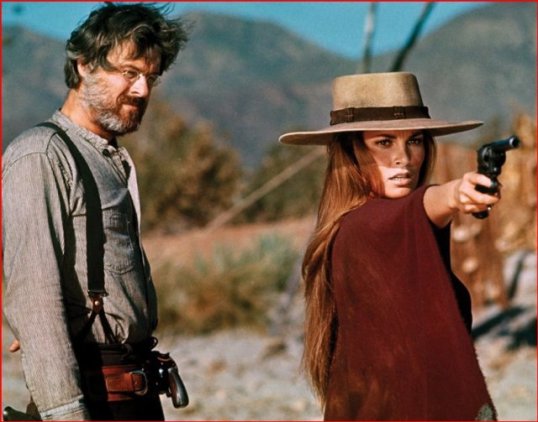

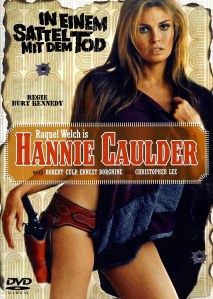

A century before Beatrix Kiddo killed Bill and The Deadly Viper Assassination Squad, there was Hannie Caulder.

A century before Beatrix Kiddo killed Bill and The Deadly Viper Assassination Squad, there was Hannie Caulder.