Welcome to Retro Television Reviews, a feature where we review some of our favorite and least favorite shows of the past! On Saturdays, I will be reviewing The American Short Story, which ran semi-regularly on PBS in 1974 to 1981. The entire show can be purchased on Prime and found on YouTube and Tubi.

This week, we have an adaptation of Flannery O’Connor’s longest short story.

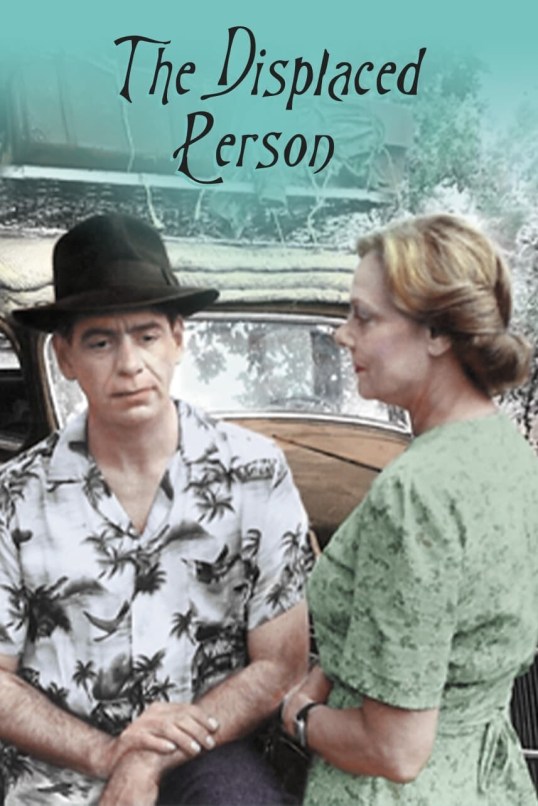

Episode #7: “The Displaced Person”

(Dir by Glenn Jordan, originally aired in 1977)

Life at a Georgia farm is thrown into turmoil when the farm’s owner, widow Mrs. McIntyre (Irene Worth), agrees to give a job to a Polish refugee named Mr. Guizac (Noam Yerushalmi). As World War II has just ended and Father Flynn (John Houseman) has assured Mrs. McIntyre that Guizac can drive a tractor, Mrs. McIntyre is happy to give Guizac a home in America. Less happy are the people who already work at the farm, most of whom see the hard-working Guizac as being a threat. Mrs. Shortley (Shirley Stoler) worries that her husband (Lane Smith) is going to lose his job to Guizac. Meanwhile, a young farmhand named Sulk (Samuel L. Jackson) enters into a business arrangement with Guizac, one that causes Mrs. McIntyre to change her opinion of Guizac. Needless to say, it all ends in tragedy.

This adaptation is based on a short story that Flannery O’Connor wrote after her own mother hired a family of Polish refugees to work at their family farm, Andalusia. This adaptation was actually filmed at Andalusia, only a few months after Flannery O’Connor’s death. The furniture seen in the house was O’Connor’s own furniture. The peacocks the drive Mrs. McIntyre crazy and which cause Father Flynn to have a religious epiphany are the same peacocks that roamed the farm when Flanney O’Connor lived there. The cemetery that Mrs. McIntyre visits is the O’Connor family cemetery. It brings a sense of authenticity to the film, one that is often missing from films made about the South.

The adaptation moves at a deliberate pace but it’s well-acted and it stays true to O’Connor’s aesthetic. Those who might complain that there are only two likable characters in the film — Mr. Guizac and Father Flynn — are missing the point of O’Connor’s story. Even Mrs. McIntyre, who initially seems to be trying to do the right thing, is blinded by the prejudices of race and class. Father Flynn never gives up on trying to redeem both Mrs. McIntyre and the rest of the world but one gets the feeling that he might be too late.

The cast is what truly makes this adaptation stand-out. Irene Worth, John Houseman, Lane Smith, Robert Earl Jones, they all give excellent performances. Samuel L. Jackson was very young when he appeared in The Displaced Person but he already had the screen presence that has since made him famous. The best performance comes from Shirley Stoler, who plays Mrs. Shortley as being a master manipulator who, unfortunately, happens to be married to a worthless man. Mrs. Shortley does what she does to protect her husband. Mr. Shortley does what he does because he’s a loud mouth bigot. Everyone has their own reasons, to paraphrase Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game. In this story, those reasons lead to tragedy.