Takashi Miike’s Audition premiered in 1999 at various international film festivals before receiving a limited theatrical release in Japan in 2000. Before this film, Miike was largely known in Japan as a director of gritty, often hyper-violent yakuza cinema, with films like the Black Society Trilogy defining his reputation. However, Audition introduced him to the world stage in a way that shocked and captivated audiences beyond Asia. It was a major step in bringing Japanese horror, or J-horror, into the international spotlight, specifically to Western viewers who had limited exposure to this distinct style of horror. While filmmakers and cinephiles such as Quentin Tarantino and Eli Roth had been fans of Miike’s earlier works, Audition was a revelation that displayed a more complex, restrained, and deeply unsettling side of Japanese horror cinema that was largely unknown to general audiences in the West.

At first glance, Audition presents itself as a simple, quiet domestic drama. The film opens with Shigeharu Aoyama, played with a gentle dignity by Ryo Ishibashi, visiting his terminally ill wife in the hospital. This opening scene is tender and somber, establishing the emotional core of the film: a man grappling with loss. The narrative then leaps seven years forward, showing Aoyama as a widower still mired in grief, living a lonely life with his teenage son, Shigehiko. Shigehiko, sensing his father’s emotional paralysis, urges him to begin moving on with his life, encouraging him to date again and escape the depression that has enveloped him since his wife’s death.

The inciting moment comes when Aoyama’s friend Yasuhisa Yoshikawa, a film producer played by Jun Kunimura, proposes a peculiar solution: to hold an audition for a fictional TV drama, the real purpose being to discreetly find a woman who could be compatible with Aoyama as a partner. The auditions, while framed as a casting call, are frankly a thinly veiled matchmaking scheme. Although initially awkward and even comical in its premise, the auditions soon reveal a darker subtext—the women are not treated as individuals with their own hopes and desires, but rather as pieces in a man’s recovery process. This treatment subtly exposes lingering misogyny entrenched within the social fabric, where the women’s autonomy is overlooked and they are reduced to roles to be performed and judged purely on superficial criteria.

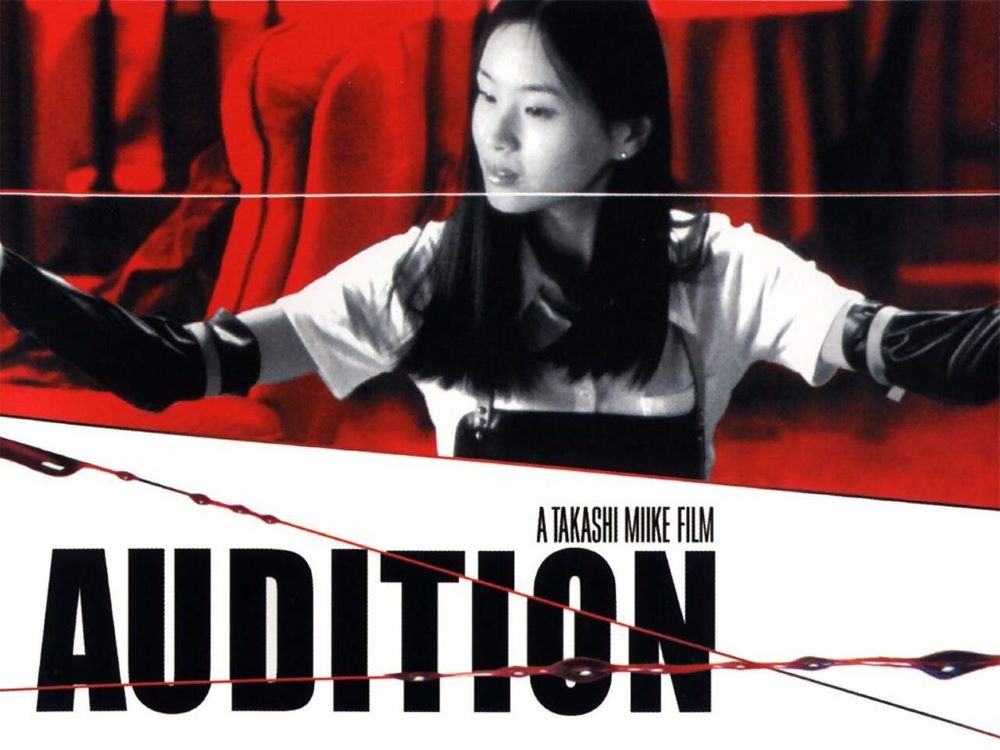

Among the candidates, one young woman stands out: Asami Yamazaki, portrayed with chilling serenity by Eihi Shiina. Asami, with her soft-spoken voice and seemingly delicate demeanor, instantly captures Aoyama’s attention. She shares a tragic backstory about her abandoned dreams of becoming a ballerina, cut short by a debilitating injury. This combination of fragility and mystery pulls Aoyama in, despite the warnings from Yoshikawa, who finds suspicious gaps in her background and troubling connections to violent incidents. What makes Asami particularly intriguing is the way Miike shapes her character with a complex duality. Outwardly, she embodies calmness and grace, which is visually reinforced through her wardrobe choices. She is often dressed in white—a color traditionally associated with purity and innocence—but she also frequently dons black latex over her white clothing. This contrast of white and black on her outfit manifests her dual nature: the peaceful façade masking a darker, far more dangerous interior.

This juxtaposition of colors is a subtle yet powerful artistic choice. It visually hints at her character’s concealed capacity for violence and control beneath a serene exterior. The black latex signals strength, mystery, and something potentially sinister, while the white suggests vulnerability and fragility. Asami doesn’t scream threat or menace; instead, she radiates an almost hypnotic calm that belies the storm hidden underneath. This visual storytelling complements the slow-building tension of the film, where the audience is continuously reminded to question appearances and expect unsettling surprises beneath the surface.

For much of the film’s first hour, Audition presents itself as a slow-burning romance between two emotionally damaged people. The pacing is unhurried, and the tone is understated and reserved, encouraging viewers to settle into the seemingly bittersweet story of a man tentatively trying to open his heart again. Yet throughout, subtle details apply pressure on this comfortable façade: Asami’s unblinking stares, her quiet stillness, and the unsettling sight of the large burlap sack sitting ominously in her sparsely furnished apartment speak volumes in silence. Miike shows a masterful ability to create an overwhelming sense of horror and dread from this sparse setting—just Asami, a burlap sack, and a phone lying on the floor become enough to chill the viewer deeply by their sheer mysteriousness and the ominous possibilities they evoke. The emptiness of the room forces attention on the few elements present, making the audience fill in unseen horrors with imagination, intensifying the tension without a single loud noise or burst of action.

The horror emerges gradually, not as a sudden rupture but as an inevitable revelation. As the film progresses, Asami’s cracks in the façade deepen, and the audience is led to an increasingly dark place where it becomes clear that almost nothing is as it seems. When the violence finally explodes, the tone shifts entirely. Miike keeps the camera steady and calm while the terror unfolds with surgical precision—a terrifying contrast to most horror films’ usual frantic editing in moments of violence. The infamous climactic scene is a masterclass in controlled horror: every movement, every sound, every visual detail is deliberate. It unfolds with a quiet, ritualistic menace that makes it impossible to look away, yet deeply uncomfortable to watch.

Asami’s violent acts are disturbing not only for their nature but for the serenity with which she carries them out. Her cold, calm demeanor during these moments reinforces her duality. The woman who once seemed so fragile now becomes merciless, completely in control, almost as if performing a deeply personal ritual. Her chilling voice remains soft, almost tender, as she methodically inflicts unimaginable pain on Aoyama, turning the hunting of the predator into a careful orchestration of revenge and self-assertion.

This transformation invites apt comparison to Annie Wilkes from Rob Reiner’s film adaptation of Stephen King’s Misery. Both characters are women whose broken pasts have twisted them into forces of violent control. Annie Wilkes, played iconically by Kathy Bates, is a former nurse whose love turns obsessive and horrifying when she imprisons her favorite author. Like Asami, Annie’s violence is not born from random cruelty but from deep emotional scars and isolation that have warped her understanding of love and power. Both women are trapped by their traumas and express that trauma through calculated violence—a grim reclaiming of agency in worlds that had silenced or harmed them. While Asami channels her rage through a cold, almost ritualistic cruelty hidden beneath an outer calm, Annie’s madness is an explosive, volatile cyclone of passion and psychosis. Both, however, show how a woman shaped by pain and repression might lash back in terrifying ways.

What made Audition stand out at the time—and still does today—is its slow-building dread and emotional complexity. Western horror in the late 1990s was dominated by slasher flicks, supernatural hauntings, and a new generation of self-referential genre films that played with tropes for laughs and jumpscares. Audition offered something completely different: a quiet, emotionally resonant story where the horror grows from the cracks in human relationships and societal expectations. Aoyama’s loneliness, his idealization of women, and his emotional blindness all play into the film’s horrifying climax, making the violence feel almost inevitable—a dark extension of the story’s psychological and social subtext.

However, Audition has often been unfairly associated by Western critics and media with the so-called “torture porn” wave of horror films that emerged in the early 2000s. This grouping overlooks the important distinction that the brutal, graphic, and extended depictions of physical and sexual torture characteristic of torture porn owe much more to the French New Extremity movement. Filmmakers like Alexandre Aja, Pascal Laugier, Xavier Gens, and Alexandre Bustillo pushed horror into territories of relentless physical torment, prolonged scenes of sexual violence—including rape—and vivid, lingering gore with films such as High Tension (2003), Martyrs (2008), and Inside (2007). These films are marked by their explicit, often shocking depiction of suffering and are designed to push the audience’s limits through sustained, graphic realism.

In contrast, Audition relies heavily on psychological tension, careful pacing, and emotional weight rather than overt gore or relentless brutality. Its moments of violence, while shocking, are part of a carefully constructed narrative about loneliness, denial, and control, creating horror through gradual revelation rather than relentless spectacle. Miike’s film helped broaden the landscape of horror by introducing a more atmospheric, character-driven terror that challenged viewers to engage deeply with the emotional and social undercurrents of fear.

When Audition reached Western film festivals and arthouse theaters, it caused a stir. Many audiences were unprepared for its unsettling mix of quiet domestic drama and savage horror. Accounts of fainting and walkouts spread quickly, but beyond the shock factor, the film earned critical praise for its artistry and unique voice. Directors like Quentin Tarantino championed Miike’s work, drawing attention not only to him but to the broader wave of Japanese horror arriving on the global stage. Audition helped open the door for landmark films like Ringu (1998) and Ju-on: The Grudge (2002), sparking widespread interest in J-horror’s more subtle, psychological approach to fear.

At its core, Audition is about appearances and the dangerous fictions people build around longing and loss. Asami embodies this perfectly—her serene outward demeanor conceals a deeply disturbed interior. The interplay of light and shadow in her wardrobe, the gentle cadence of her speech compared with her violent deeds, all speak to the duality of her character. She is both victim and predator, delicate and deadly, calm and terrifying.

In this way, Miike invites viewers not just to witness horror but to feel it as an inevitable expression of human vulnerability and social repression. Violence here is less an escape than a dark reflection of isolation and a desperate reclaiming of power when all other avenues are closed.

Looking back, Audition stands as the film that propelled Takashi Miike beyond obscurity and established him as a singular voice in global cinema. It was one of the earliest J-horror films to find a meaningful audience in the West, breaking new ground in how horror could be crafted—fear born from loneliness and cultural repression, told with unsettling subtlety. It remains a haunting, unforgettable film that changed horror’s shape and opened many eyes to the frightening potential lurking beneath calm surfaces.