Twin Peaks: The Return was full of creepy characters but the Woodsmen may have been the creepiest.

“Gotta light?”

Twin Peaks: The Return was full of creepy characters but the Woodsmen may have been the creepiest.

“Gotta light?”

The year is 1989 and the Cold War is coming to an end. Colonel Jack Knowles (Roy Scheider) was a hero in Vietnam but now, years later, his eagerness to fight has made him an outsider in the U.S. Army. Most people would rather that Knowles simply retire but, as long as there are wars to be fought, Knowles will be there. His only friend, General Hackworth (Harry Dean Stanton), arranges for Knowles to be assigned to an outpost on the West German-Czechoslovakia border. As soon as he arrives, Knowles starts to annoy his superior officer, Lt. Col. Clark (Tim Reid). When Knowles sees a Czech refugee gunned down by the Soviets while making a run for the border, he unleashes his frustration by throwing a snowball at his Russian counterpart. Like Knowles, Col. Valachev (Jurgen Prochnow) is a decorated veteran who feels lost without a war to fight. Knowles and Valachev are soon fighting their own personal war, even at the risk of starting a full-scale conflict between their two nations.

The year is 1989 and the Cold War is coming to an end. Colonel Jack Knowles (Roy Scheider) was a hero in Vietnam but now, years later, his eagerness to fight has made him an outsider in the U.S. Army. Most people would rather that Knowles simply retire but, as long as there are wars to be fought, Knowles will be there. His only friend, General Hackworth (Harry Dean Stanton), arranges for Knowles to be assigned to an outpost on the West German-Czechoslovakia border. As soon as he arrives, Knowles starts to annoy his superior officer, Lt. Col. Clark (Tim Reid). When Knowles sees a Czech refugee gunned down by the Soviets while making a run for the border, he unleashes his frustration by throwing a snowball at his Russian counterpart. Like Knowles, Col. Valachev (Jurgen Prochnow) is a decorated veteran who feels lost without a war to fight. Knowles and Valachev are soon fighting their own personal war, even at the risk of starting a full-scale conflict between their two nations.

The Fourth War was one of the handful of films that John Frankenheimer directed for Cannon Films. Much as he did with The Manchurian Candidate, Frankenheimer mixes serious thrills with dark satire in The Fourth War. Frankenheimer gets good performances from the entire cast, especially Scheider and Prochnow. The real star of the movie is the snow-covered landscape, which Frankenheimer turns into a metaphor for the entire Cold War. When Knowles and Valachev end up throwing punches on a frozen lake that’s breaking apart underneath their feet, it is not hard to see what Frankenheimer’s going for with this film. Released shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, The Fourth War is an underrated thriller that deserves to be rediscovered.

“It was a dream! We live in a dream!”

— Phillip Jeffries (David Bowie) in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992)

Even among fans of the show, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is controversial.

If you read Reflections: An Oral History of Twin Peaks, you’ll discover that many members of the television show’s cast either didn’t want to be involved in the film or didn’t care much for it when it came out. Fearful of being typecast, Kyle MacLachlan only agreed to play Dale Cooper on the condition that his role be greatly reduced. (Was it that fear of being typecast as clean-cut Dale Cooper that led to MacLachlan later appearing in films like Showgirls?) Neither Lara Flynn Boyle nor Sherilyn Fenn could work the film into their schedules.

When Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me premiered at Cannes, it was reportedly booed by the same critics who previously applauded Lynch’s Wild at Heart and who, years later, would again applaud Mulholland Drive. When it was released in the United States, the film was savaged by critics and a notorious box office flop. Quentin Tarantino, previously a fan of Lynch’s, has been very outspoken about his hatred of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. When I first told people that we would be looking back at Twin Peaks for this site, quite a few replied with, “Even the movie?”

And yet, there are many people, like me, who consider Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me to be one of David Lynch’s most haunting films.

It’s also one of his most straight forward. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is a prequel, dealing with the events leading up to the death of Laura Palmer. Going into the film, the viewer already knows that Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) is full of secrets. They know that she is using drugs. They know that she is dating Bobby (Dana Ashbrook), while secretly seeing James (James Marshall). They know about her diary and her relationship with the reclusive Harold (Lenny Von Dohlen). They know that she is a friend to innocent Donna Hayward (Moria Kelly, somewhat awkwardly taking the place of Lara Flynn Boyle). Even more importantly, they know that she has spent the last six years of her life being abused by BOB (Frank Silva) and that BOB is her father, Leland Palmer (Ray Wise). The viewer starts the story knowing how it is going to end.

Things do get off to a somewhat shaky start with a nearly 20-minute prologue that basically plays like a prequel to the prequel. Theresa Banks, who was mentioned in the show’s pilot, has been murdered and FBI director Gordon Cole (David Lynch) assigns agents Chester Desmond (Chris Isaak) and Sam Stanley (Kiefer Sutherland) to investigate. Chester and Sam’s investigation basically amounts to a quick reenactment of the first season of Twin Peaks, with the agents discovering that Theresa was involved in drugs and prostitution. When Chester vanishes, Dale Cooper is sent to investigate. Harry Dean Stanton shows up as the manager of a trailer park and David Bowie has an odd cameo as a Southern-accented FBI agent who has just returned from the Black Lodge but otherwise, the start of the film almost feels like a satire of Lynch’s style.

But then, finally, we hear the familiar theme music and the “Welcome to Twin Peaks” sign appears.

“And the angel’s wouldn’t help you. Because they’ve all gone away.”

— Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee), Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992)

A year has passed since Theresa Banks was murdered. The rest of the film deals with the final few days of the life of doomed homecoming queen Laura Palmer. Laura smiles in public but cries in private. She is full of secrets that she feels that she has to hide from a town that has literally idolized her. She has visions of terrifying men creeping through her life and each day, she doesn’t know whether it will be BOB or her father waiting for her at home. She knows that the world considers her to be beautiful but she also know that, within human nature, there is a desire to both conquer and destroy beauty. When she sleeps, she has disturbing dreams that she cannot understand but that she knows are important. At a time when everyone says she should be happy to alive, all she can think about is death. Everywhere she goes, the male gaze follows and everything that should be liberating just feels her leaving more trapped. For all the complaints that Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is somehow too strange to be understood, it’s not a strange film at all. This is David Lynch at his most straight forward. Anyone who thinks that Laura’s story is incomprehensible has never been a 17 year-old girl.

This is the bleakest of all of David Lynch’s films. There is none of broad humor or intentional camp that distinguished the TV show. After the show’s occasionally cartoonish second season, the film served as a trip into the heart of the darkness that was always beating right underneath the surface of Twin Peaks. It’s interesting how few of the show’s regulars actually show up in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. None of the characters who represented goodness are present. There’s no Doc Hayward. No Sheriff Truman. No Deputies Andy or Hawk. No Pete Martell. No Bookhouse Boys. Scenes were filmed for some of them but they didn’t make it into the final cut because their tone did not fit with the story that Lynch was seeking to tell. The Hornes, Dr. Jacoby, Josie, none of them are present either.

Instead, there’s just Larua and her father. As much as they try to deny it, Laura knows that she is going to die and Leland knows that he is going to kill her. Killer BOB and the denziens of the Black Lodge may be scary but what’s truly terrifying is the sight of a girl living in fear of her own father. Is Leland possessed by BOB or is BOB simply his way of excusing his own actions? If not for Leland’s sickness, would BOB even exist? When Laura shouts, “Who are you!?” at the spirit of BOB, she speaks for every victim of abuse who is still struggling to understand why it happened. For all the talk of the Black Lodge and all the surreal moments, the horror of this film is very much the horror of reality. Leland’s abuse of Laura is not terrifying because Leland is possessed by BOB. It’s terrifying because Leland is her father

David Lynch directs the film as if it where a living nightmare. This is especially evident in scenes like the one where, at the dinner table, Leland switches from being kindly to abusive while Laura recoils in fear and her mother (Grace Zabriskie) begs Leland to stop. It’s a hard scene to watch and yet, it’s a scene that is so brilliantly acted and directed that you can’t look away. As brilliant as Ray Wise and Grace Zabriskie are, it’s Sheryl Lee who (rightly) dominates the scene and the rest of the film, giving a bravely vulnerable and emotionally raw performance. In Reflections, Sheryl Lee speaks candidly about the difficulty of letting go of Laura after filming had been completed. She became Laura and gave a performance that anchors this absolutely terrifying film.

“Mr. Lynch’s taste for brain-dead grotesque has lost its novelty.”

— Janet Maslin

“It’s not the worst movie ever made; it just seems to be”

— Vincent Canby

If you need proof that critics routinely don’t know what they’re talking about, just go read some of the original reviews of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.

And yet, having just rewatched the show and now the movie, I can understand why critics and audiences were baffled by this film. This is not Twin Peaks the TV show. There is no light to be found here. There is no comic relief. (Even Bobby Briggs, who had become something of a goofy anti-hero by the time the series ended, is seen here shooting a man in the head.) There is no exit and there is no hope. In the end, the film’s only comfort comes from knowing that Laura was able to save one person before dying. It’s not easy to watch but, at the same time, it’s almost impossible to look away. The film ends on Laura’s spirit smiling and, for the first time, the smile feels real. Even if she’s now trapped in the Black Lodge, she’s still free from her father.

Since this was a prequel, it didn’t offer up any answers to the questions that were left up in the air by the show’s 2nd season finale. Fortunately, those questions will be answered (or, then again, they may not be) when the third season premieres on Showtime on May 21st.

Previous Entries in The TSL’s Look At Twin Peaks:

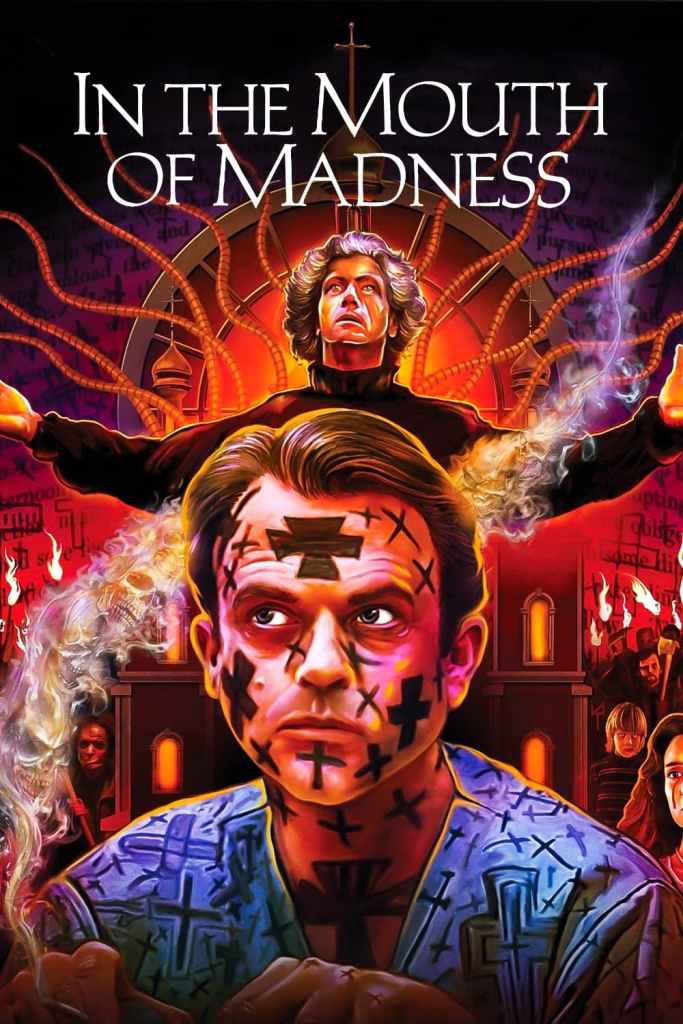

In the Mouth of Madness is one of those films that in essence seems like a good idea, but later becomes strange and unwieldily to the point that you have to ask yourself “What am I watching, and why did I do so?”

Jumping right of of Memoirs of an Invisible Man, In the Mouth of Madness reunites Sam Neill (Jurassic Park) with Carpenter. Neill plays John Trent, an Insurance Investigator whose latest case deals with a horror writer named Sutter Cane (Jurgen Prochnow). Cane’s novels have the strange ability to affect anyone who reads them. After Cane’s own agent/publicist falls his influence and is abruptly killed, Trent is sent to find Cane (who is missing) and help bring back his latest story , “In the Mouth of Madness” to the agency. When he sets off on his mission, he slowly finds his sense of reality unraveling.

If Neill’s character is the Scully, Julie Carmen (Fright Night Part II) plays the Mulder in this equation. Sent along with Trent, her character witnesses more of the horror than he does. She’s the audience witness for a while and proves Trent wrong when he’s ready to disbelieve what’s occurring. She good here, but her reactions, mixed with Trent’s had me slapping my forehead. I’ll get to that in a moment.

I’m told that the film is something of a homage to H.P. Lovecraft’s stories. While I’ve never read Lovecraft, I’m somewhat familiar with the Cthulhu myths and there does seem to be some tentacled beasts near the last third of the film. Overall, some of those references escape me. The movie’s fun in a Donnie Darko mind bending way and it’s that strangeness that actually helps the film a little.

I hate the fact that Sam Neill’s character simply won’t accept that what’s happening is real. I’m not a big fan of stuffing square pegs into round holes. If it doesn’t fit – you’re being told “This is how it goes”, and you’re seeing that’s how it’s happening – then why in the world are you still holding on to the same train of thought that isn’t working / fitting the situation? I found that extremely annoying. It’s almost the opposite of Slither, where it didn’t take long for the characters to recognize that:

1.) People were becoming zombies.

-And-

2.) It just wasn’t normal for the situation. Accept and adjust. Cover your mouth.

Overall, it was okay, but it really needed something. I’m just not sure what.

“There are things in this world that go beyond human understanding.”

John Carpenter’s reputation as one of the great American horror directors rests on his ability to merge the cinematic with the philosophical—to craft films that stay frightening not because of what they show, but because of what they suggest. Yet by the early 1990s, Carpenter’s once unshakable relationship with audiences had weakened. His influence remained undeniable, but several of his later films seemed to miss the spark that defined Halloween, The Fog, or The Thing. Then arrived In the Mouth of Madness (1995), a work that signaled a late creative resurgence. It paid intelligent homage to two pillars of horror literature—Stephen King and H. P. Lovecraft—while offering a disturbing reflection on authorship, sanity, and the power of belief. The film reasserted Carpenter’s command not only over frightening imagery but also over the psychological territory that underpins enduring horror.

At a narrative level, In the Mouth of Madness follows John Trent (Sam Neill), an insurance investigator known for exposing fraud and deception. His skepticism becomes both his strength and undoing. Trent is hired by publishing executive Jackson Harglow (played by the legendary Charlton Heston) to locate Sutter Cane, a best-selling horror novelist whose disappearance threatens both the company’s finances and the stability of Cane’s obsessed fanbase. Every sign points to something far stranger than a publicity stunt. Cane’s readers are exhibiting troubling behavior, as though the author’s new book has triggered more than just entertainment—it has become contagion.

Carpenter crafts Trent’s descent into uncertainty with meticulous pacing. At first, Neill’s character regards the assignment as routine, dismissing the hysteria surrounding Cane’s novels as marketing excess. But when his investigation hints that the locations and events in Cane’s fiction may correspond to real places and real disturbances, the film begins to twist the rational into the uncanny. The story’s sense of unreality builds with deliberate restraint—incidents grow progressively stranger, but never so overt that Trent can confidently identify what’s madness and what’s truth. Carpenter thrives on this ambiguity, pulling both protagonist and viewer into an atmosphere where logic erodes and fiction itself seems to rewrite reality.

Accompanying Trent on his search is Linda Styles (Julie Carmen), the publisher’s editor assigned to ensure the investigation runs smoothly. While her performance has sometimes been considered subdued, Styles functions as the audience’s second perspective: observant, mildly skeptical, and gradually aware that the world around her no longer behaves according to its former rules. Carpenter positions her as a necessary counterpoint to Trent’s brittle rationalism, highlighting the conflict between recognizing patterns and succumbing to fear. As they move closer to locating Cane, their surroundings take on the familiar haunted quality of an archetypal New England town—Hobb’s End—built from the shared DNA of King’s Castle Rock and Lovecraft’s Arkham. The town becomes more than setting; it is a physical embodiment of literary influence and psychological instability.

The choice of Sam Neill proves essential to the film’s success. His trademark combination of intelligence and emotional vulnerability allows Trent’s transformation from calculating skeptic to disoriented seeker to feel natural rather than theatrical. Few actors could portray a man so evidently rational who nonetheless finds himself seduced by forces his disciplined mind cannot resist. Neill’s body language carries much of the horror; his expressions shift between dry disbelief and quiet terror, suggesting that intellect offers no protection once perception itself begins to betray you. Carpenter exploits this performance with close framing and asymmetric compositions, visually trapping Trent in spaces that subtly curve or distort. The director’s technical command ensures that even ordinary scenes seem charged with quiet wrongness.

While In the Mouth of Madness never references the mythos of Lovecraft by name, its influence saturates the film. Lovecraft’s hallmark—cosmic indifference—exists here not through tentacled gods but through the crumbling borders between fiction and the human mind. The suggestion is that the very act of creating and consuming stories might awaken something ancient and uncontrollable. When Trent confronts the nature of Cane’s work, Carpenter’s direction avoids overstatement. Instead of grand confrontations, he conveys horror through disorientation—the feeling that language, images, and even memory are slipping toward incoherence. Reality itself becomes a character, unstable and untrustworthy.

Jürgen Prochnow’s portrayal of Sutter Cane adds another layer of unease. His calm, confident manner diverges from standard portrayals of deranged genius. Prochnow makes Cane unnerving precisely because he appears so certain of his vision. The author views himself not as a mere storyteller but as a conduit, claiming that what he writes merely reveals a preexisting truth. Through him, Carpenter explores a potent question that haunts all creators: does imagination serve human purpose, or is it an independent force that uses human minds as tools? Cane’s conviction blurs that line, turning the creative process into possession. To audiences familiar with the concept of “mad artists” in literature, his belief offers both fascination and dread.

Carpenter imbues this theme with visual invention. The cinematography and set design combine the mundane with the surreal—painted walls pulse, corridors bend, horizons vanish. Rather than relying on excessive gore or digital spectacle, the director emphasizes textures and shadows, creating optical unease rather than overt shock. The town of Hobb’s End seems perpetually detached from time, its streets looping back on themselves. By employing low, creeping camera movements and deliberate color desaturation, Carpenter evokes a dreamscape decaying from within. The film’s sound design—especially Carpenter’s own pulsating score, co-composed with Jim Lang—heightens that tension with rhythmic basslines reminiscent of a heartbeat slowing to a stop. Every technical choice reinforces the narrative’s central sensation: uncertainty.

Michael De Luca’s screenplay deserves particular credit for its clever structure. The film is framed as a story told from inside an asylum, immediately hinting that the perspective may be unreliable. This framing allows Carpenter to shift between psychological thriller and cosmic horror without losing cohesion. As viewers, we are made complicit in Trent’s investigation but warned not to trust his perceptions. The resulting experience is disorienting yet coherent—a cinematic maze where each turn feels inevitable once taken. The writing never lingers long on exposition, instead suggesting connections through implication and repetition. In this way, De Luca’s script succeeds in translating Lovecraftian dread into visual terms: a fear of knowledge itself.

Very few directors have managed this particular tone as successfully. Lovecraft’s fiction often resists cinematic adaptation precisely because its greatest horror lies in what cannot be shown. In the Mouth of Madness solves this problem by making the act of storytelling itself the subject of terror. By focusing on an author whose imagination reshapes reality, Carpenter transforms literary horror into filmic language. In doing so, he edges close to achieving what decades of other attempts had failed to capture—a true Lovecraftian mood rendered on screen, grounded not in spectacle but in existential dislocation.

Despite its craftsmanship and intelligence, In the Mouth of Madness struggled at the box office upon release. Its ambiguity, self-reflexivity, and intellectual leanings proved challenging for mid-1990s audiences who expected more conventional scares. Yet over time, the film’s reputation has flourished. Today, it is often regarded as the concluding entry in Carpenter’s loosely connected “Apocalypse Trilogy,” following The Thing (1982) and Prince of Darkness (1987). All three films share a fascination with humanity confronting forces it cannot comprehend—scientific, metaphysical, or divine. In each, Carpenter presents apocalypse not as fiery destruction but as revelation: the moment when human understanding collapses under greater cosmic truth. That philosophical core links these works across more than a decade of filmmaking.

Revisiting In the Mouth of Madness now, one is struck by how prophetic it feels. Its concerns about cultural contagion and media-induced madness anticipate contemporary conversations surrounding viral misinformation, fandom extremism, and the blurring between online identity and reality. The “disease” in the film—ideas that rewrite perception—mirrors our present anxiety about the stories and images that shape collective belief. Carpenter’s horror, always grounded in social awareness, here expands into a warning about a world unable to distinguish narrative invention from lived experience.

Even limited in budget, Carpenter demonstrates confident control of visual tone and rhythm. His filmmaking reminds viewers that suggestion often unsettles more deeply than spectacle. Rather than overwhelming audiences with jump scares, he leads them through gradual disintegration, where each logical step seems to justify the next until coherence itself fractures. The film invites reflection rather than relief, leaving viewers haunted by the possibility that the boundaries between art and life are far thinner than comfort allows.

While Carpenter would go on to direct more films after 1995, In the Mouth of Madness stands as one of his last profoundly accomplished achievements. It encapsulates the elements that made his earlier works enduring: tight pacing, minimalist storytelling, and ideas that resonate beneath genre tropes. The film’s legacy continues among filmmakers who explore metafictional or cosmic horror, from Guillermo del Toro’s long-sought adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness (a feat that may never come to fruition outside of concept art and videos) to the psychological labyrinths of contemporary horror auteurs. Though Carpenter’s film never directly adapts Lovecraft, it succeeds where many literal adaptations fail—by preserving the essence of incomprehensible terror rather than translating it into spectacle.

Ultimately, In the Mouth of Madness remains a rare horror film that asks not just what we fear, but why we need fear in the first place. Its central notion—that imagination itself can undo reality—strikes at the heart of storytelling. Carpenter’s mastery lies in letting that idea linger long after the credits roll. What begins as an investigation grows into a philosophical nightmare, compelling viewers to question how much of their world is built from collective belief. In that sense, the film transcends its genre to become one of Carpenter’s most unsettling reflections on human perception. Decades later, its message still resonates: the stories we consume may shape us more profoundly than we realize.